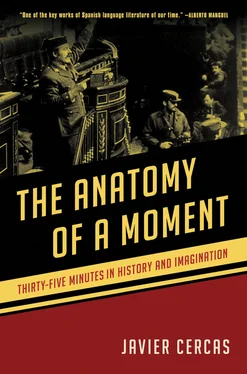

The following morning was the most frenetic of Major Pardo Zancada’s life: almost single-handedly, without the help of Torres Rojas — whom he tried to phone over and over again at his military government office in La Coruña — without the help of San Martín — who had left first thing for a training camp near Zaragoza to supervise tactical exercises in the company of General Juste — Pardo Zancada prepared the Brunete Armoured Division for a mission that he still didn’t know and sketched out a programme of operations that each of its units should carry out: seizing the radio and television stations, taking up advance positions in strategic locations in Madrid — in the Campo del Moro, the Retiro, the Casa de Campo and the Parque del Oeste — their subsequent deployment in the city. Mid-morning he finally managed to speak with Torres Rojas, who rushed to catch a regular flight to Madrid dressed in his combat uniform and tank-driver beret, ready to stir his former unit to rebellion with his reputation as a tough leader loyal to his officers built up during his recent years in command. Pardo Zancada picked up Torres Rojas at Barajas airport just after two in the afternoon, and shortly afterwards had lunch with him in the headquarters canteen in the company of other commanders and officers surprised by the unexpected visit by their former general, at the same time that, in the Santa María de la Huerta parador, where he was lunching with General Juste on their way to Zaragoza, Colonel San Martín received a prearranged warning from Pardo Zancada according to which everything in the division was ready for the coup. At this moment San Martín must have hesitated: to return with Juste to headquarters meant risking that the commander of the Brunete might abort the plot; not to return meant perhaps excluding himself from the glory and yields of the triumph: the ambition to enjoy those, allied to the arrogance of the once all-powerful head of the Francoist intelligence services and his knowledge of the difficulties inherent in moving a division if the one doing it is not its natural commander, he convinced himself he could handle Juste and that he should return to his command post at El Pardo, which would eventually turn out to be one of the causes of the failure of the coup. This is how at half past four in the afternoon Juste and San Martín make a surprise reappearance at headquarters and this is how a few minutes before five, after troops have been confined to barracks, Major Pardo Zancada finally takes the floor to address the commanders and officers of all ranks he himself has summoned to that anomalous meeting and who now pack Juste’s office. Pardo Zancada’s speech is brief: the major announces that in a matter of minutes an event of great significance will occur in Madrid; he explains that this event will be followed by the occupation of Valencia by General Milans; he also explains that Milans is counting on the Brunete Division to occupy the capital; also, that the operation is directed from the Zarzuela Palace by General Armada with the consent of the King. The reaction of the majority of the meeting to Pardo Zancada’s words wavers between repressed joy and expectant but not dissatisfied seriousness; the commanders and officers await the verdict of Juste, whom Torres Rojas and San Martín try to win over to the cause of the coup with calming words and appeals to the King, Armada and Milans, and whom San Martín convinces not to call his immediate superior, General Quintana Lacaci, Captain General of Madrid, who is not aware of anything. After a few minutes of anguished hesitation, during which the uprising of 1936 goes through Juste’s head and the possibility that, if he opposes the coup, his officers might wrest away his command of the division and execute him then and there, at ten past five in the afternoon the commander of the Brunete Armoured Division makes an anodyne gesture — some of those present interpret it as a frustrated attempt to adjust his tortoiseshell glasses or to smooth his meagre grey moustache, others as a gesture of consent or resignation — pulls his chair up to his desk and pronounces three words that seem to be the penultimate sign that the coup will triumph: ‘Well, carry on.’

At the very same time, barely five hundred metres from the Cortes, at Army General Headquarters in the Buenavista Palace, everything is ready for the final signal to occur. There, in his new office as Deputy Chief of the Army General Staff, General Alfonso Armada has just arrived from Alcalá de Henares, where that morning he had participated in a celebration commemorating the foundation of the Parachute Brigade, has changed out of his ceremonial uniform and into his everyday one and waits but not impatiently, without even turning on the radio to listen to the debate of investiture of the new Prime Minister, for some subordinate to burst in and tell him of the assault on the Cortes. But what Armada — perhaps the most monarchist military man in the Spanish Army, until four years ago the King’s secretary, for the last several months many people’s candidate in the political village of Madrid to lead a coalition or interim or unity government — is especially waiting for is the subsequent call from the King asking him to come to the Zarzuela and explain what’s going on in the Cortes. Armada has good reasons to expect it: not only because he’s sure that, after almost a decade and a half of being his most dependable confidant, the King trusts him more than anyone else or almost anyone, but also because after his painful exit from the Zarzuela the two had reconciled and in recent weeks he has warned the monarch on a great many occasions about the risk of a coup and insinuated that he knows its ins and outs and if it finally occurs he could control it. Then, once in the Zarzuela, Armada will take charge of the problem, just like he used to do in the old days: backed by the King, backed by the King’s Army, he will go to the Cortes and, without having to make too much of an effort to convince the political parties to accept a solution that in any case the majority of them already considered reasonable long before the military took to the streets, he’ll liberate the deputies, form a coalition or interim or unity government under his leadership and bring tranquillity back to the Army and the nation. That’s what Armada expects will happen and that’s what, according to the golpistas ’ predictions, will inevitably end up happening.

So at six in the evening on 23 February the essential elements of the coup were all ready and in the places assigned by the golpistas : six buses full of Civil Guards under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Tejero were about to leave the Motor Pool to head for the Cortes (and another under the command of Captain Muñecas was about to do so from Valdemoro); the military commanders of the region of Valencia had opened their sealed orders with Milans’ instructions and, once the units were stocked up with fuel and ammunition, the barracks prepared to open their gates; the brigade and regiment commanders of the Brunete were just leaving headquarters for their respective command posts with operational orders drawn up by Pardo Zancada and approved by Juste containing concrete instructions on their priority objectives, deployment zones and occupation and surveillance missions; though not in his office but in that of General Gabeiras — his immediate superior and Chief of the Army General Staff, who just summoned him to discuss a routine matter — General Armada waits at Army General Headquarters for the phone call from the Zarzuela. Half an hour later Lieutenant Colonel Tejero bursts into the Cortes and the coup is unleashed. The taking of the Cortes was perhaps an easier than expected success: neither the police who guarded the building nor the deputies’ bodyguards offered the least resistance to the attackers, and a few minutes after entering the chamber, when the interior as well as the exterior of the Cortes was under his control and the mood of his men was euphoric, Lieutenant Colonel Tejero telephoned Valencia euphorically to give the news to General Milans; it was an easy success, but not a complete success. Given that it was meant to be the gateway to a soft coup, Tejero’s orders were that the occupation of the Cortes should be bloodless and discreet: he was only to suspend the session of investiture of the new Prime Minister, to detain the parliamentarians and maintain order pending the Army now in revolt coming to relieve him and his Civil Guards and General Armada, giving the hostages a political exit; miraculously, Tejero managed to keep the occupation bloodless, but not discreet, and that was the first problem for the golpistas , because a hail of bullets in the Cortes broadcast live on radio to the whole country gave the scenery of a hard coup to what was meant to be a soft coup or meant to keep up the appearance of a soft coup and made it difficult for the King, the political class and the general public to willingly give in to it. It could have been much worse, of course; if, as at the beginning seemed inevitable to those who heard the shooting on the radio (not to mention those who suffered it in the chamber), as well as indiscreet the operation had been bloody, then everything would have been different: because there’s no turning back from deaths, the soft coup would have become a hard coup, and the bloodbath may have been inevitable. However, as things happened, in spite of the violence of the operation’s mise-en-scène nothing essential stood in the golpistas ’ way ten minutes into the coup: after all a mise-en-scène is only a mise-en-scène and, although the shooting in the chamber would undoubtedly force certain adjustments to the plan, the reality is that the Cortes was hijacked, that General Milans had proclaimed martial law in his region and had sent forty tanks and one thousand eight hundred soldiers of the 3rd Maestrazgo Mechanized Division out onto the streets of Valencia, that the Brunete Armoured Division was in revolt and their AMX-30 tanks ready to leave the barracks and that in the Zarzuela the King was on the point of calling Army General Headquarters to speak to General Armada. If it’s true that the fate of a coup is decided in its first minutes, then it’s also true that, ten minutes after its start, the 23 February coup had triumphed.

Читать дальше