It was hard to separate the Berezovsky team members from their inherent bias against Putin. These three intelligent people—Felshtinsky, Litvinenko, and Berezovsky—had looked at highly suspicious circumstances through a shared lens of anger, victimization, and vengefulness, and reached the most extreme possible conclusion: that Putin had conspired in the bombing of fellow citizens as part of a diabolical power grab by Russia’s intelligence services. The circumstantial evidence was certainly prejudicial against the FSB. Yet as far as I could see, it would be very difficult to validate the three men’s conclusions.

A contrarian attitude is healthy when it comes to conspiracies; though many are suggested, few turn out to be real. I myself learned that lesson on my first foreign posting, in the intrigue-filled Philippines, a place where there were no simple answers. The locals spun the most fantastic tales, into which it was easy to be drawn. The coup-prone counterintelligence officers of the Philippine Army were even more dangerous, skillfully persuading most of the foreign correspondents that President Corazon Aquino was destined to fall and that they—these handsome officers—would take her place. She didn’t fall, and those who succumbed to the disinformation were embarrassed. David Briscoe, my Manila boss at The Associated Press, possessed one of the wisest approaches to seemingly sinister events. “Sometimes the answer is right there on the surface,” Briscoe used to say of conspiracies, or the lack thereof.

So, what about the apartment blasts? Did the FSB and possibly Putin slaughter hundreds of Russians to achieve their aims? Putin himself called the Ryazan theory madness. “There are no people in the Russian secret services who would be capable of such a crime against their own people,” he said. “The very allegation is immoral.”

Yes, the possibility was intriguing, made so by the writings of Felshtinsky, ultra-smart Russian journalists such as Pavel Voloshin, who led the reporting on it at the time, and foreign correspondents such as David Satter. I was reluctant to dismiss them, even though my nonsense detector rejected their stated or implied judgments that a conspiracy was to blame. After all, the authorities had tried to sweep Ryazan under the carpet.

I reconsidered the competing theories—that it was al-Qaeda, Boris Berezovsky, Chechens, rogue FSB agents, or perhaps someone completely different. What if one group had blown up the first four buildings, but copycats had planted the Ryazan bomb? An FSB link of some sort seemed certain—former or current agents were basically caught in the act. But did that mean it was a plot approved at the top? Were they rogue operators hired to carry out a mission for al-Qaeda or the Chechens? Were other forces at work?

There did seem to have been a plot afoot to bomb the Ryazan building. But it did not seem possible for a journalist to solve the mystery of who organized it. As far as the allegation of a conspiracy at the top levels of government, the most that anyone could say with absolute certainty was that the Kremlin had been guilty of its customary indifference to the welfare of Russian citizens.

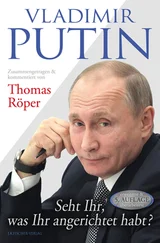

In the years to follow, Putin would preside over a revival of Russian prosperity at home and influence abroad, fueled by a great flood of wealth from the country’s tremendous store of oil and natural gas. Russia possessed 26 percent of the world’s natural gas—the largest reserves of any country—and the seventh-largest oil reserves, at 6.6 percent. Putin would trumpet the return of a Great Russia and tell his people to be proud of themselves and their past. He would glorify leaders and events regarded as odious by much of the outside world; Josef Stalin’s murderous 1930s purges, he would say, had been exaggerated by Russia’s enemies. (As prime minister, Putin had toasted Stalin on the dictator’s birthday. And he threw a lavish, nationally televised Kremlin party to honor Felix Dzerzhinsky, the brutal founder of Cheka, the early Bolshevik-era prototype of the KGB. It all smacked of a personal love affair. “This profession employs those who love our Motherland and who are selflessly devoted to their people,” Putin told a room of intelligence agents. “…Those who are ready to execute the most difficult and dangerous tasks at the first order work in the security services.”)

The Russian people would respond to Putin’s steady withdrawal of their individual liberties with obedience combined with defiant nationalism, a standard set four centuries earlier under Ivan IV. In the West, Ivan’s nickname, Grozny, was translated as “Terrible”—but to Russians, Ivan was “Fearsome” or “Awesome,” an image that Putin would successfully cultivate.

Putin maintained no torture or execution chambers. Yet his matter-of-fact responses to the domestic assassinations that occurred with some regularity invited the impression abroad that he was cold-blooded and at minimum a protector of murderers.

Consider the month of October 2006. A killer fired four shots into Anna Politkovskaya, killing the journalist in her apartment house. Three days later, gunmen killed banker Alexander Plokhin, the head of a Moscow branch of Vneshtorgbank. Days after that, the victim was Anatoly Voronin, business director of the ITAR-TASS news agency. Finally, a lone assailant used a Kalashnikov with a silencer to execute Dmitry Fotyanov, a mayoral candidate in the mining town of Dalnegorsk. None of the murders was solved.

Litvinenko was assassinated the following month in London. The United Kingdom concluded that a former Russian intelligence agent had done the killing, and sought his extradition from Russia. Putin could have acquitted himself and Russia as a whole by cooperating with Britain. Instead, he rejected the extradition request and looked on approvingly as the suspected assassin won election to the national parliament, thereby gaining immunity from prosecution within Russia while a wanted man in Europe. Opinion abroad hardened that Putin was, in one way or another, complicit in the murder. I could think of no similar behavior by the president of an industrialized country. Putin seemed to be deliberately putting himself in the same camp as the world’s most disreputable leaders.

It was altogether possible, of course, that Putin and his circle intended to convey precisely the menacing impression that foreigners had of them, sending a message that said, Don’t mess with Russia. But that seemed like overthinking. The greater likelihood was that Putin was simply being Putin.

CHAPTER 3

Getting to Know The Putin

Morning in Russia—at a Price

EVEN THE MOST TOTALITARIAN GOVERNMENTS ARE PUBLIC RELATIONS conscious. Journalists can usually count on at least one reasonably informed—if not entirely believable—person to serve as the face of the country. Afghanistan’s brutal ruler Najibullah himself met routinely with reporters during the late 1980s and early 1990s; Uzbekistan’s Islam Karimov delegated the task to an economic lieutenant; and Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir had Islamic radical Hassan al-Turabi speak to me, in the days before Bashir threw him in prison.

In Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin there was no such person. Putin’s usual spokesman was Dmitri Peskov, baby-faced and charming. But I did not want to hear from a mere spin doctor. I wanted access to an actual player, a participant in events, so that I could better understand the Kremlin’s view of why certain things happened as they did. I got nowhere.

As one of Peskov’s assistants explained, Putin’s men saw no benefit at the moment in candid conversation with someone writing for an essentially Western audience. Whatever they said would be misperceived, and in any event why should they care what the West thought about them?

Читать дальше