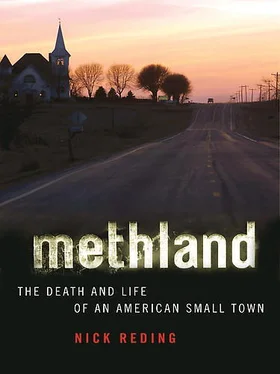

Shortly after Christmas 2006, Oelwein’s Main Street looked like a movie-set version of its former self. Phase II of Mayor Murphy’s revitalization was complete. The street, which had been ripped up six months before, was neatly and freshly paved. The updated, evenly graded sidewalks were cleanly plowed of snow. Saplings had been planted along both sides of the street, and though they were leafless in winter, they nonetheless promised new life in the spring. Above them, the refurbished streetlamps were hung with wreaths and wrapped in red velvety ribbon. No fewer than nine new businesses lined the sidewalks, all of them in long-empty storefronts, including Las Flores, the Mexican restaurant that had opened that fall.

Las Flores is equidistant from the movie theater on the north and the Do Drop Inn on the south, and is right across the street from Von Tuck’s Bier Haus. One night I had dinner at Las Flores with Larry Murphy, Nathan Lein, and Clay Hallberg. It had been months since all three men had seen one another; life had gotten busy, and then suddenly the holiday season had descended, replete with its innumerable chores. The 2006 Christmas pageant, which had been the new and improved Oelwein’s de facto coming-out party, had gone swimmingly, by all accounts. Now, life was settling once again into the slower rhythms of what promised to be a long, cold Iowa winter. At six P.M. on the night we met for dinner, the large digital thermometer in the Iowa State Bank parking lot said it was seven degrees, with a wind chill of twenty-four below zero.

I came into Las Flores with Nathan. We’d been pheasant hunting all afternoon in the cattail breaks and creek bottoms that bisect the land of a farmer known around town as Puffy. Clay and Murphy were already seated in a booth when we got to the restaurant. Keeping the indoor temperature tolerable, if not quite comfortable, seems to be a point of pride in northern Iowa in the winter. As such, it was cold inside the restaurant—not enough to see your breath, but enough so that Murphy and Clay, like the other dozen or so customers, still wore their parkas, albeit unzipped to the middle of their chests to expose heavy wool sweaters beneath.

Las Flores is the only outward sign, save for occasional sightings in the aisles of the Dollar General or Kmart, of the growing but largely invisible Mexican immigrant population in Oelwein. According to a local RE/MAX broker who specializes in rental properties, there are neighborhoods, particularly in the town’s southwest quadrant, where Nathan lives, in which thirty or forty Mexicans share a few small two-bedroom homes. Most work at the John Deere plant over in Waterloo, though until January 2006 a few dozen had been employed by the now-defunct Tyson meat-packing operation in Oelwein. For well over a century, ever since the Pirillos and the Leos opened their bakeries and restaurants, immigrants in Oelwein have used food as an assimilative lever. Indeed, the mélange of immigrant cuisine and American curiosity is a principal socializing force in our culture, a fact that was once as true in San Francisco’s Chinatown as it is today in small towns throughout the United States, as the number of Mexican immigrants has grown alongside a taste for tacos and fajitas.

The menu at Las Flores is enormous, as though trying to please both the locals and the Mexican workers. There’s a selection of authentic Mexican food, which includes several fish dishes marinated in lime juice and sautéed in homemade sauces; a selection of Tex-Mex, dishes invariably ending with the word gringo (as in taco gringo ); and a selection devoted solely to fajitas. That the fajitas section is at once the largest and the one with the fewest entries, a kind of billboard built into the menu itself, speaks loudly to the fact that, according to Eduardo, he sells a hundred “chicken sizzlers” to every tilapia al ajillo .

Murphy and Nathan and Clay all thought the change to Oelwein, at least as measured by food, was great. Overstating the case more than slightly, Murphy slipped into mayor mode while perusing the margarita list and said, “Where else in this county—or even in Iowa—can you get good Mexican, Chinese, and Italian food on the same block?”

Clay was smoking a Marlboro Light as he looked at the menu, tilting his head by degrees, trying to line up his eyes with the reading-glass half of his bifocals. Looking over the frames, he said, “Um, have you heard of Des Moines, Murph? If I’m not mistaken, isn’t that in Iowa?”

“Even Greek food,” said Murphy, pressing the point. He was referring to Two Brothers Greek Restaurant, a block north, whose windows had neon signs advertising steaks and pizza. Nowhere on the menu was there a trace of tsatsiki, taramosalata, or even a gyro.

“Since when does Salisbury steak count for Greek food?” said Nathan.

Murphy was unfazed, though his smile served as a slight crack of irony in his facade. “To me, it’s just incredible the ethnic diversity in our little town.”

“Scribe,” Nathan said to me, “my guess is that Murph wants you to write that down.”

Heritage in Oelwein is not something that is taken for granted; in a farming culture predicated on the changeability of seasons, history is in some ways what there is to hold on to. And yet the Irishman, the German, and the Norwegian sitting in Las Flores that night truly celebrated the influx of Mexicans into their town. It seemed only fitting, therefore, that Las Flores occupies the ground floor of one of the oldest and prettiest buildings in Oelwein. Four stories tall and made of hand-laid stone with a vaulted entryway, it’s one of the most interesting as well, the street-level windows tinted nearly black, adding a sleek, modern aesthetic to the place. The restaurant itself is sixteen hundred square feet, enough to accommodate fourteen tables and nine booths. The smoking section seems to expand and contract depending on shifts in the clientele. The walls are fake brick from the baseboard to the sconces, and above that, synthetic adobe painted a pale yellow. Every few feet, and in no apparent pattern, hangs some kind of artisanal memento—a garish poncho, a gigantic sombrero, and a photo of a shoeless peasant strumming his guitar next to a burro. The cheesiness in no way undermines the authenticity. To the contrary, what makes Las Flores enduring—in an old building in an old American town—is in some ways the paradox of its novelty.

That Mexican immigrants stereo typically work hard, I was told, is considered the highest form of praise in Oelwein. That they are brown-skinned and speak a language which sounds fast in a town where people typically take their time formulating their sentences is, just as with the Italians in the early twentieth century, going to take some getting used to. There is respect, to be sure, though with predictable limits. As the real estate broker told me, “Not many landlords are lining up to rent to Mexicans.” The feeling that the new arrivals are taking away jobs from the locals is up for debate, and does not seem—by my count, anyway—to be the flash point it is sometimes portrayed as being in newspapers across the country. On the other hand, the fact that the immigrants lack medical insurance, says Clay, is a tremendous strain on the already overtaxed local hospital. And then there is the question of the drugs, particularly meth. According to Jeremy Logan, meth is distributed by a few well-placed Mexican dealers who are increasingly busy ever since the Combat Meth Act went into effect.

Still, no one was on a witch hunt. Far from it. Everyone at the table—the doctor, the mayor, and the prosecutor—accepted that Eduardo, the owner of Las Flores, was probably an illegal immigrant without feeling the need to verify it as fact. As Nathan said, you wouldn’t have to look very far into anyone’s history around those parts, his own included, to find a similar story told in another time. He instinctively grasped what Representative Souder—for one—did not, which is that if you encourage people to come to your country, you cannot then hold it against them for showing up. As a prosecutor, Nathan simply didn’t ask people’s status. That way, he wouldn’t be party to forcing someone out “through the gate,” as he put it, “which is left perpetually and invitingly open.”

Читать дальше