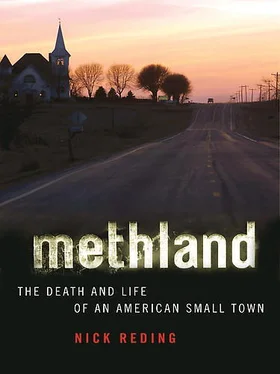

And then one night, Lori went to a bar. It was a Friday, and Lori, fresh off her shift trimming hams, was damn square sure she deserved a cold one. In fact, she deserved about eight cold ones, which would be one for every year since she’d had the last beer. Then an old friend offered Lori a bit of crystal meth nicely arranged in the middle of a piece of aluminum foil. Lori lit a match, held it beneath the foil to liquefy and then vaporize the dope, and smoked it through a glass tube. For a woman like Lori, who eight years before used to snort an eighth of an ounce of meth a day, smoking one measly foil somehow didn’t seem like that big of a deal.

Nor did she think it was anything to worry about when, a few days later, she decided to make a quick fifty bucks selling a small amount of crystal that a friend needed to get rid of in the worst way. Lori had just that week started renting her own apartment; now she wanted, as a means of making things up to her son, to help him pay off some old debts. So Lori quit the night-shift job at Wendy’s and began selling small amounts of meth. Then, because she just couldn’t pass up such a peach of an opportunity, she approached a Mexican trafficker in Des Moines and made a deal with him. By 2001, two years after she got out of prison, Lori was moving so much Mexican-made crystal from so many different traffickers that she bought a nightclub—just as she’d done back in 1989—to help launder the money.

At the time, Lori was hitting the meth pretty hard herself. She does not, she says, remember sleeping more than one night a week, at most. Because she was still on parole and had to submit to urinary analyses every couple of weeks, she paid the four-year-old daughter of one of her employees five dollars apiece for cups of urine to sneak into her tests. She bought a house and paid her son’s debts. She bought another Jaguar. She got reacquainted with an old boyfriend and planned to marry him soon. Then, on October 25, 2001, she sold a quarter pound of meth to an undercover narcotics officer in the Ottumwa Police Department. Shortly thereafter, Lori was arrested, tried, convicted, and once again sentenced, this time to seven and a half years in the medium-security federal work camp for women in Greenville, Illinois.

The woman who founded the Midwest meth trade fifteen years before had now helped usher in the drug’s new era by teaming up with the DTOs, which had grown in part out of Lori’s original link to the Amezcua brothers. Once again, the tenth-grade dropout from Ottumwa was at the head of a trend sweeping across the nation. By 2001, all the pieces were in place. The newest era of the meth epidemic was in full swing.

The United States is broken into seven regions by the Drug Enforcement Administration. Operations in each region, all of which are secret, are coordinated by a special agent in charge (SAC), whose DEA experiences run the gamut from U.S. street assignments to operational tours of duty in foreign countries. SACs are invaluable in understanding the recent history of narcotics in the United States and in the world—for instance, the broad context in which Lori Arnold’s Stockdall Organization fit in with the DTOs. In 2006, the piece of the puzzle that was still missing for me was exactly how the DTOs had become so powerful so quickly. While the discovery of the industrial meth market had been an instrumental part of the process, that alone didn’t account for how five mega-organizations had evolved from the business put into place by the Amezcua brothers before their capture in 1996. Ironically, I was told by two former DEA SACs that it was a blow to the Colombian cocaine cartels in Cali and Medellín that provided the final, triumphant piece for the formation of the five Mexican DTOs.

Operation Snowcap was the code name for DEA’s 1987 multinational cocaine-control effort in Central and South America. The approach was twofold: to seize large amounts of cocaine and to cripple Colombian distribution routes that passed through Guatemala. By almost any measure, Snowcap—coupled with operations to limit distribution via the so-called Caribbean Corridor feeding the Miami port of entry—was a huge success, resulting in a dramatic decrease in the amount of Colombian cocaine entering the United States. But Snowcap also had an unforeseen consequence: it redirected the distribution of cocaine from the Colombian cartels to what were then small-time Mexican narco-operations.

Back in the 1980s, Guatemala was what was called a “trampoline” state. Planes coming from Colombia laden with cocaine would stop there to refuel before “bouncing” to locations in Texas, Arizona, and California. In that way, Guatemala played the same role the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and the Bahamas did with marine delivery of cocaine via the Caribbean. As soon as Operation Snowcap limited the Cali and Medellín cartels’ two principal options for delivery into the United States, the Colombians approached the Mexican organizations that controlled access to the twenty-five hundred miles of essentially unprotected U.S. border. The Colombian cocaine and heroin empire, which had for years depended on cooperation with Guatemala and the Bahamas, was now dependent on Mexico. According to Tony Loya, the ex-SAC who ran Operation Snowcap from Guatemala City, “What happened was not the lesser of two evils; it was the greater. Our success with Medellín and Cali essentially set the Mexicans up in business, at a time when they were already cash-rich thanks to the budding meth trade in Southern California.”

In essence, the Mexican organizations based along the border—in Tijuana, Juárez, Nogales, Nuevo Laredo, and Matamoros, each of which would become the base of operations for the five DTOs—were able to heavily influence the price of cocaine by controlling its entry into the United States. DEA’s success with Snowcap essentially awarded the Mexican organizations gate-keeping rights in the most valuable narcotic market on earth, at the same time as those organizations were building a separate but related business in the meth trade. What the Mexican organizations did subsequently, however, was far more significant. For the favor of allowing the Colombians to ship their cocaine into the U.S. marketplace, the DTOs demanded payment not in cash, but in product. For every kilo of cocaine the Mexicans let cross their border, they kept a kilo for themselves.

A senior American official assigned to the U.S. embassy in Mexico City who also worked on Operation Snowcap explained the result this way: “By controlling the entry point for all of the cocaine into the U.S., the Mexicans controlled the price. How else will Colombia get its product to its customers? It depends on the DTOs. By taking payment in cocaine and distributing it themselves, the DTOs created fifty percent market share overnight. If you control the price, along with half the retail and distribution, you basically own the business.”

The shift in power from the Colombian cartels to the Mexican traffickers had two major consequences. First, the DTOs grew rich enough to buy larger amounts of precursors to make meth. Second, DEA was unable to adjust to the new paradigm. The Medellín and Cali cartels had relied on Bahamians, Dominicans, and Americans to distribute and sell their cocaine. Those businesses were, according to the embassy official in Mexico City, highly centralized. Their movements were predictable, and decisions came from the top—most famously from Pablo Escobar. In contrast, the DTOs, said the official, are decentralized and protean. They rely only on Mexican nationals to distribute and sell their products, making it harder for DEA to infiltrate the organizations. Because individual distributors have more decision-making power, the movements of the organization as a whole are much less predictable.

Читать дальше