One of the attractions at Las Flores is the sixty-four-ounce margarita, which is drawn from a clear plastic machine inside of which three large mechanical spatulas stir separate vats of red, green, and yellow slush. Murphy ordered strawberry, no salt, while Nathan asked for regular, extra salt. Meantime, Clay lit another cigarette. In front of him was a twenty-four-ounce Diet Coke in a brown plastic glass with crushed ice. Clay had been sober five months and counting—long enough to have had the Intoxilock removed from his truck.

Clay had also, though, been having trouble at Mercy Hospital, where he was chief of staff. After ordering tortillas and salsa, chimichangas, and fajitas, Murphy and Nathan listened as Clay launched into a critique of the hospital’s owner, Wheaton Franciscan Health Care, which drew heavily on the anti-corporate formulations of Noam Chomsky—Clay’s latest hero. Clay, a devout but non-churchgoing Methodist, was a fan of God in his specific way and suspicious of churches generally—especially the Catholic church. According to him, the Wheaton Franciscans, technically a nonprofit order of the church, had “systematized their disrespect for human life to such a degree” that Clay was either going to quit or be fired as chief of staff. What galled him even more than what he deemed the hospital’s substandard equipment was the fact that, in order to save money, patients’ tests were being sent by computer to doctors in Australia and India to be read and analyzed, with the results e-mailed back.

“I mean, what the fuck?” said Clay. “How ’bout no, okay? How ’bout, I’m not trusting my mammogram to some guy in Mumbai? It’s not that they’re not talented doctors,” he went on, “it’s that they’re not here. Part of being a doctor is holding your colleagues accountable. If some guy in India misreads my patient’s biopsy and the patient dies of cancer, do you think we’ll get the guy from India deposed at the civil hearing that takes my license and sues me for all I’m worth?”

Clay stared at Nathan, who stared back impassively. As things around him heated up—Clay’s temper, for instance—Nathan’s heart rate seemed to slow considerably.

“Not likely,” said Clay, finally answering his own question.

“Okay,” said Nathan.

Murph said enthusiastically, “I’ll be darned.”

As Clay saw it, the hospital and insurance systems lacked critical oversight. For example, Wheaton Franciscan had recently begun placing physicians, most from India, in underserved areas across the rural United States. Like the Mexicans who worked in the slaughterhouses, the Indian doctors would work for less money than the American doctors. The trouble was, said Clay, few of the foreign doctors stayed for the entire two-year rotation, for the reason that the Indians’ cultural milieu didn’t mesh with that of places like Oelwein. These shortened terms, said Clay, drove the quality of care down and destabilized the staff. At Mercy, he continued, three doctors had left early in the past eighteen months, keeping the ER in utter turmoil. What’s more, insurance companies used high doctor turnover as a criterion for raising premiums. Practicing medicine in Oelwein felt more and more difficult, said Clay, and morale was low.

Murphy nodded sympathetically. He said, “The insurance companies have a monopoly. What can you do?”

What Clay was considering doing was quitting. He’d been thinking about “freelancing,” as he put it, by taking pay-by-the-hour jobs in rural emergency rooms.

“That’s the only place I can do any good,” said Clay. “I mean, who needs you more than an elderly lady with no insurance who comes to the ER at two P.M. on a Tuesday?”

“What’s stopping you?” asked Nathan.

“My dad,” said Clay. “This hospital—it’s where Dad practiced for half a century. Our family practice is our family. This whole town, kind of, is our practice. I don’t know how to just walk away from that.”

“That’s just the rub,” said Nathan.

“Yes,” agreed Murphy, “it truly is.”

Still, the men had a lot to be happy about that December. One of Clay’s two daughters had just had her first child out in Sacramento, California, where she lived with her husband. Nathan had won convictions against the twin brothers Tonie and Zonie Barrett—the former for first degree murder, the latter for conspiracy—in the June 2005 killing of Marie Ferrell. And Murph was getting good feedback on the improvements around town. The new library was a smashing success, and its patrons enjoyed two dozen computers with free high-speed Internet connections. Not only had Oelwein High School avoided bankruptcy, but 2006 was the first year in a decade that the student body had grown—by three students. Though the call center talks had stalled, Murphy and the city council had persuaded Northeast Iowa Community College to build a campus at the Industrial Park. The Regional Academy for Math and Science was also planning to move there, just west of the college. Murphy and the city council had decided to build a technology center on the remaining land as a gamble to lure more businesses, especially now that they could offer a new septic system. Finally, the second-largest ethanol plant in Iowa had recently been built seven miles west of town; this had resurrected some traffic on the local rail lines, allowing several Oelwein businesses to save significantly on transportation costs. Thanks to the plant, corn prices had risen by five cents a bushel. The hope was that things would just keep getting better and better.

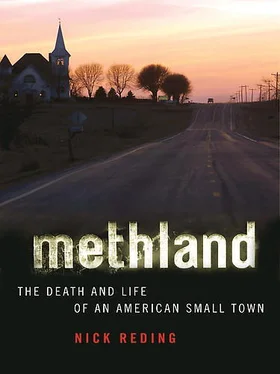

Perhaps the most encouraging yardstick was that methamphetemine, measured by the number of labs that had been dismantled, had all but ceased to be an issue around Oelwein. In fact, the Cop Shop hadn’t had a single call about a lab in nearly six months, dating back almost exactly to the week when ground was broken for the Main Street refurbishments. Things truly felt different around Oelwein since I’d first been there. In June 2005, it was not uncommon to see meth cooks in the headlights of your car late at night, riding around the town’s more peripheral neighborhoods single-batching dope in bottles strapped to their mountain bikes. Just a year and a half later, the streets no longer felt unsafe, or like you weren’t sure what would happen if you got a flat tire in the wrong place at the wrong time. Houses no longer blew up in the middle of the afternoon, and no one phoned in reports to the police about a strong smell of ether coming from a neighbor’s garage. Even the Do Drop Inn felt vaguely (if somewhat lamentably) secure.

In fact, by Christmas 2006, Oelwein had come to represent the hopefulness of thousands of small towns across the nation that had seen major drops in the number of lab busts. The Combat Meth Act had been in place for six months, and national newspapers had largely stopped reporting on the epidemic; the rural United States was no longer portrayed in the sour, Lynchian light in which it had been cast since 2004. These were all reasons to celebrate, indeed, sitting in a booth at Las Flores as the snow began to fall outside the window.

The basic functions of the Combat Meth Act were to limit the amount of cold medicine consumers could buy in the United States; to allow the State Department to withdraw foreign aid from nations that fail to stop the diversion of pseudoephedrine and ephedrine to the illicit market; and to impose quotas on how much pseudoephedrine and ephedrine U.S. pharmaceutical companies could import. In a way, the Combat Meth Act accomplished what Gene Haislip, long since retired from DEA, had considered the most important aspect of the battle against meth for nearly twenty-five years: to monitor the importation and exportation of its precursors.

The quotas imposed by the Combat Meth Act set off a chain reaction of economic events that Haislip could have imagined only in his wildest dreams. Fearful of restrictions on pseudoephedrine, Pfizer, the world’s largest cold medicine manufacturer and the maker of Sudafed, began using a chemical called phenylephrine to make 50 percent of its cold products. Phenylephrine, approved in 1976 by the FDA, cannot be made into methamphetamine. The switch caused the nine companies that produce the world’s supply of pseudo to decrease their production, thereby reducing the amount of pseudo available for narco-traffickers to turn into meth. According to one of the last meth articles written by Steve Suo for the Oregonian , U.S. drug companies cut imports of pseudo by more than two thirds in 2006, to 275 tons from 1,130 tons the year before. The U.S. State Department convinced the Mexican government to halve imports of pseudo and to bar middlemen from the process, causing North America’s aggregate imports of meth’s principal precursor to drop 75 percent between 2004 and 2006. Suo also reported that, based on DEA statistics, meth’s purity had fallen to an average of 51 percent, down from 77 percent the year before. The degradation in quality, Suo wrote, was a sure sign that far less meth was being produced. Mom-and-pop meth production was down not just in Oelwein, but everywhere.

Читать дальше