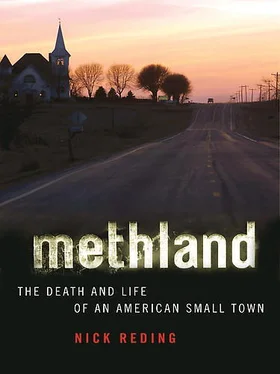

In 2005, when I called Dr. Clay Hallberg, the Oelwein general practitioner, and asked him to characterize the meth epidemic in his hometown, Clay had told me that meth was “a socio cultural cancer.” What he meant, he said, was that, as with the disease, meth’s particular danger lay in its ability to metastasize throughout the body, in this case the body politic, and to weaken the social fabric of a place, be it a region, a town, a neighborhood, or a home. Just as brain cancer often spreads to the lungs, said Clay, meth often spreads between classes, families, and friends. Meth’s associated rigors affect the school, the police, the mayor, the hospital, and the town businesses. As a result, said Clay, there is a kind of collective low self-esteem that sets in once a town’s culture must react solely to a singular—and singularly negative—stimulus.

It was clear from the minute I got to Oelwein that Clay’s position as a small-town doctor put him in the best possible place from which to observe the meth phenomenon. What would become clear to me over the next three years, though, is that the very thing he hoped to treat in others, the “collective low self-esteem,” also took a brutal, withering toll on Clay himself. The first time we talked, he’d likened each day at work to running into a burning motel and having fifteen minutes to get everyone out. The motel was Oelwein, and Clay never had enough time before he had to retreat, fearful he too would burn alive. Indeed, three years later, Clay would need saving. It’s partly in this way that his story parallels that of his hometown.

Clay and his twin brother, Charlie, were adopted when they were one year old from the orphanage in Waterloo, Iowa, by Doc Hall-berg, Oelwein’s general practitioner since 1953. Clay and Charlie are identical twins. They have opposite dominant eyes and hands, and part their hair on opposing sides—Clay on the right, Charlie on the left. Clay plays the bass and Charlie the drums. Clay earned degrees in biology and chemistry; Charlie, meanwhile, majored in philosophy and theology, with a minor in Egyptology.

From an early age, the boys had promiscuous interests, including chemistry; they used their chemical know-how to make pipe bombs and once blew up a neighbor child’s sandbox. They had a shared active sense of humor as well, and delighted in giving guests glasses of water, only to announce minutes later they’d gotten the water from the toilet. For the first few years of their lives, their mother would turn their shared crib upside down and stack books on top of it to keep them from getting loose in the house and wreaking havoc. As teenagers in the 1970s, neither twin was, to put it politely, unfamiliar with narcotics. After graduating together from the University of Northern Iowa, in Cedar Rapids, Clay went to medical school at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, and Charlie to law school at Creighton University. In 1987, Clay, recently married and finished with his residency, came back home to join his father’s practice. Shortly thereafter, Charlie moved into a house down the street from Clay’s and began work as the Fayette County public defender.

Clay is five feet eight and weighs 160 pounds. He has a welder’s forearms and the hands not of a musician or a surgeon, but of a farmer: thick in the meat, with large fingers and deep creases in the palms. Clay’s brown hair is going gray (“salt-and-turd,” he calls it), and he wears it combed back. He has a short, manicured goatee and intense grayish-blue eyes behind fashionable frameless glasses. In contrast to his wife’s deep northern Missouri drawl, Clay’s accent is more Minnesotan, extending each opening syllable toward the innards of a word. His lexicon is unmistakable and specialized; he often says “how ’bout” and “okay,” as when responding in the negative to a request: “How ’bout no way, okay?” Young men and women with multiple piercings “have gone face-first into a tackle box.” Bars are “unsupervised outpatient stress-reduction clinics that serve cheap over-the-counter medications with lots of side effects.”

Clay goes to work every day in a small brick building across the street from Mercy Hospital. Mercy, as it’s called, is an imposing monolithic structure built sixty years ago by the Catholic church. Next door is the high school and a small residential neighborhood. Beyond that, the prairie starts in earnest, lonely and flat and constant. From the window in the waiting room of the Hallberg Family Practice, you can see a lot of sky, which makes the clutter of Clay’s tiny office at the back of the building feel that much more profound. There’s a desk and two chairs, one of which is inaccessible given the boxes of patient files that line the floor in stacks. On one wall are shelves covered with antique doctor’s implements; many of them once belonged to Clay’s father, who finally retired when his wife was killed in a car accident in 2003. Next to these are a hundred or so books attesting to the extent of Clay’s duties: Clinical Neuroanatomy , Pathophysiology of Renal Disease , General Ophthalmology , Patten’s Foundations of Embryology .

True to his roots, Clay not only sees patients in the exam room across the hall; he drives to their houses and farms, and also works two nights a week in the emergency room. He has delivered babies in the backs of cars, and once, in a barn. A few years ago, he served as assistant county coroner, which is to say, assistant to his father. He’s also chief of staff at Mercy. In terms of what there is to see around Oelwein, Clay has seen it.

Contrary to what many people might think, the rural United States has for decades had higher rates of drug and alcohol abuse than the nation’s urban areas. If addiction has a face, says Clay, it is the face of depression. Bad genes don’t help, either, says Clay, but all genes, bad or good, are susceptible to a poor environment. He knows of what he speaks. Back in the mid-1970s, after getting his B.S., Clay was back in Oelwein, casting about for something to do with his life. His father, Doc Hallberg, was abusive—a disciplinarian who limped around the rural towns of Fayette County for forty years performing minor medical miracles, all the while suffering from debilitating arthritis in his right leg, which, thanks to polio, is eighteen inches shorter than his left and compensated by a substantial shoe lift. Clay was good at giving his father reasons to be stern. He played in a band, had long hair, and did a lot of cocaine. His love of homemade explosives had not abated. One time, when the high school was closed because of a snow day, Clay set off a pipe bomb on the campus lawn, just to see what would happen. The next morning, the Oelwein newspaper called it a terrorist attack and demanded that the culprit be hunted down and prosecuted federally. (Clay was never caught.) The more Clay bounced around intellectually beneath his father’s brutal, withering glare without being able to land on something either of them found meaningful, the more Clay did drugs. Finally, he says, he realized he was either going to medical school or going to jail.

Things in Oelwein at that point were just starting to deteriorate economically. It would be a few more years before the sky fell, once the Chicago Great Western and Illinois Central closed operations in town and the farm crisis struck, but Clay attributes much of his anger and malaise to a simple socioeconomic postulate: “If you got no money, you can’t go see the band. And if you can’t see the band, you’re fucked.” What he means is that, without good jobs, little disposable income remains in the community to be spent at all manner of locally owned businesses, including at the bars. And during the last good days of the 1970s, Oelwein bars were known from Waterloo to Wenatchie for having the best local bands in the Upper Mississippi River watershed.

Читать дальше