For several weeks during 1986, according to Rexinger, he worked to change the language of Haislip’s bill in a way that would exempt Warner-Lambert from the potential bane of federal importation oversight. When DEA and Haislip continued to resist his pleas, said Rexinger, he had no choice but to get the White House involved by making a phone call to, as he proudly told Suo in 2004, “the highest levels of the United States government.”

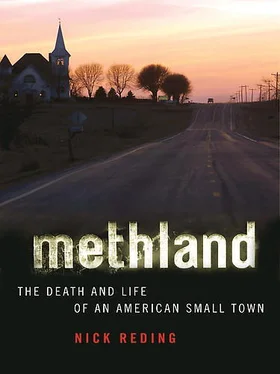

By the time Attorney General Edwin Meese III presented Haislip’s bill to Congress in April 1987, five years had passed since Haislip had initially imagined nipping meth production in the bud. Meantime, the Amezcua cartel had spread throughout California and the Desert West, and had linked up with Lori Arnold’s Stock-dall Organization in Iowa, which by now was well on its way to producing its own industrially manufactured P2P meth. The language in Haislip’s bill proposing oversight of ephedrine had been drastically altered as well, allowing for the drug to be imported in pill form with no federal regulations whatsoever. All that meth manufacturers had to do in order to continue making the drug would be legally to buy pill-form ephedrine in bulk and crush it into powder—a small, added inconvenience. What Haislip had imagined as an early answer to a still-embryonic drug threat instead became both a mandate and a road map for meth’s expansion.

In 1987, the year that Cargill cut wages at its Ottumwa meatpacking plant from $18 an hour to $5.60 with no benefits, Lori Arnold sold a pound of pure, uncut crank for $32,000. This meant that with the very first ten pounds produced at her superlab, she had paid off the $100,000 initial investment in equipment and chemicals and had cleared a profit of nearly a quarter of a million dollars, or over a century’s worth of median wages for an Ottumwa adult that year. Meanwhile, she was still buying ten pure pounds at a time of Mexican Mafia dope from California, at $10,000 a pound, which she then sold for three times the price, again making nearly a quarter of a million dollars every time one of her runners returned from the West Coast.

Where crank’s personality converges with its mathematics is this: No one with whom I spoke, and this includes varsity-level addicts like Roland Jarvis, can physically handle snorting, smoking, or shooting 98 percent pure methamphetamine. So while Lori only sold her product uncut, each pound, once it was distributed, equated to three or four pounds of ingestible crank, and probably more, given that each dealer along the line was likely to continue cutting it—with bleach, laundry detergent, or baking soda. Seen that way, Lori’s lab wasn’t producing ten pounds every forty-eight hours; it was producing the eventual equivalent of thirty to forty pounds. (By that stretch, the biggest labs in the Central Valley of California today would be producing the so-called street equivalent of up to five hundred pounds a day, while an Indonesian megalab would make five thousand pounds of saleable meth each week.) In one month alone during Lori’s prime, that’s somewhere on the order of a quarter ton of meth being distributed in the relatively underpopulated environs of the central Midwest. Add to that the dozen or so big loads she was getting from California each month, and it’s easy to see how Lori was, by her own admission, involved in one manner or another with “thousands of people” and making “hundreds of thousands of dollars monthly.” When pushed for an answer, Lori admits that she has no idea how much she made, in pounds or dollars.

When Lori first got into meth, a gram would last her an entire weekend. By 1991, Lori was snorting up to three grams a day. She remembers not sleeping for weeks at a time. She wore, she says, a lot of hats. Multiple-business owner, mother, drug baron: Without the meth, she could never have done it all. She was, she says, one of the main employers in Ottumwa, and a benevolent one, at that. She donated plenty of money to the local police and to the county sheriff. She planned to open a day care center and video game arcade next to the Wild Side, so local kids would have somewhere to go while their parents were in the bar. Together, Lori and meth were an antidote to the small-town sense of isolation, the collective sense of depression and low morale that had settled on Ottumwa since most farms went belly-up, the railroad closed, and the boys at the meatpacking plant lost their jobs.

If you ask her, Lori Arnold will say she did more for the state of Iowa than all the politicians put together, who let the place go to hell overnight. People were proud of her, she says, and they should have been: she gave them back the life that the government and the corporations took away. If there was ever a problem with meth, says Lori, it wasn’t with the clean dope she sold. Her dope wouldn’t do anything freaky to you. It was the rot-gut the batchers cooked up that made people crazy. And it was always Lori’s plea sure to put those people out of business—it was her civic duty to keep the likes of Roland Jarvis from selling too much crap-batch, getting people paranoid and blathering on about black helicopters and heads in trees. In Lori’s reality, she was a businesswoman, not a drug dealer in what she calls “the classic sense.” She’s right, insofar as she had an unprecedented vertical monopoly, which she claims to have run at least in part to assuage the detrimental effects of the very monopolies like Cargill and Iowa Beef Packers that were born in that same era of deregulation. Add to this that Lori’s rise required putting home cooks—the Iowa Hams of the meth world, if you will—out of business, and the self-styled Robin Hood of crank begins to look awfully corporate. At a deeper strata of irony, consider that Lori almost single-handedly ushered into the Midwest the next generation of the meth epidemic, which would be controlled by five Mexican drug-trafficking organizations that today enjoy the same kind of market control of meth that Cargill enjoys with respect to the food industry.

Perhaps inevitably, like Roland Jarvis, the kind of small-time tweaker for whom she had the utmost disdain, Lori did see a helicopter, though in her case it was real. It hovered over her house one day in 1990 while agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) took photos of her meth lab in the woods. Later that day, Lori was zooming around town in her green Jaguar Sovereign doing errands when she got the call from a stable boy that things were getting a little weird out at the farm. There were cars parked along the country roads, said the boy, and men with binoculars trained on the place. That night, Lori says, the feds sent in an army: ATF, FBI, DEA—you name it. By morning, she was in the local jail, telling jokes to the agents who stood guard. After all, says Lori, if you don’t have a sense of humor, what do you have left?

Six months later, Lori Arnold’s crank empire fell apart when she was convicted in federal court in the Southern District of Iowa of one count of continuing a criminal enterprise; two counts of money laundering; one count of carrying and using a firearm in conjunction with drug trafficking; and multiple counts of possession, distribution, and manufacture of methamphetamine. Floyd Stockdall was tried separately and sentenced to fifteen years in Leavenworth prison, where he died of a heart attack two months before he would have been paroled. Lori got ten years in the federal penitentiary in Alder-son, West Virginia, and was released after serving eight, on July 2, 1999. Her son and only child, Josh, was fifteen years old; Lori had been gone for half his life. By then, the meth business in the Midwest had mutated into something Lori couldn’t believe, though she was quick to comprehend that it was a new, much more fully developed phenomenon than that which she’d created along with the Amezcuas. And once Lori identified a spot for herself in the new order, she did the thing she’d been doing all her life: She went right back into business.

Читать дальше