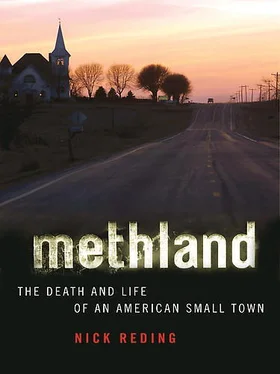

One of seven step-and half-siblings, Lori was born and raised in Ottumwa in a family that she describes as studiously normal and benign. Despite this, Lori dropped out of high school as a freshman and began living in an Ottumwa rooming house where, in the evenings, there was a running poker game. The landlady was also a madame. In exchange for room and board, Lori and her young cohorts could either agree to sleep with the men who played cards or deliver illegally prescribed methedrine pills, an early form of pharmaceutical meth, to the landlady’s clients. Lori chose the latter; thus her career (along with her legend) was born.

Lori kept herself housed by delivering and selling “brown and clears,” as pharmaceutical meth was called during the 1970s, when it was prescribed by the millions as a weight-loss aid and antidepression drug. The landlady got most of Lori’s profits, though, and to make ends meet, Lori still had to work six days a week at a local bar. (In Iowa minors can serve alcohol despite being legally unable to buy it.) By fifteen, Lori was married. By sixteen, she was divorced and was attending high school once again. By seventeen, she had dropped out for good; her peers, she says, seemed to her like children. By eighteen, she was married to Floyd Stockdall, who had come to Ottumwa from Des Moines in order to retire, at the ripe old age of thirty-seven, as the president of the Grim Reapers motorcycle gang.

Lori and Floyd moved into a cabin along the Des Moines River outside Ottumwa, where their only child, Josh, was born. Left alone to raise a son while Floyd pursued his retirement hobbies of drinking, playing pool, and selling cocaine, nineteen-year-old Lori became suicidally depressed. The bar, she now realized, had been her lifeline. In addition to the money she made, the people there were her people, the only family of which Lori ever felt a true part. Without the bikers and the factory workers with whom she had all but grown up, Lori felt horribly lost and alone; her life had become an interminable slog. Worse yet, Floyd was an alcoholic, and beat her whenever he drank.

Then one day Floyd’s brother stopped by the cabin. He, too, was a Grim Reaper, and he had with him some methamphetamine, a.k.a. biker dope, which had been illegally synthesized at a lab in Southern California. This was 1984, and the Reapers were just beginning to sell meth whenever they could get it from Long Beach. There, according to DEA, former Hells Angels had gone into business with maverick pharmaceutical company chemists in order to produce saleable quantities of highly pure, powdered methamphetamine. Lori’s brother-in-law cut her two lines on the kitchen table inside her run-down shack on the Des Moines River on a sunny, clear Saturday afternoon. Of the experience, Lori, who was no stranger to narcotics, says simply that she had never felt so good in all her life. The singularity of that feeling is what would soon connect Ottumwa to a nascent California drug empire. In doing so, a major piece of the meth-epidemic puzzle would fall into place.

The first day Lori got high, she went to the bar. She says she’d been given a little meth to sell because Floyd’s brother wanted to see what kind of a market Ottumwa might prove to be. Lori gave away half the meth, knowing intuitively that this would help hook her customers. The other half quickly sold out. In the process, she made fifty dollars. What she found, though, was worth millions, for Lori Arnold knew almost immediately that dealing meth was what she’d been born to do. It was the answer not just to her prayers, but to Ottumwa’s, which for three long years had been pummeled by the farm crisis into a barely recognizable version of its former proud self. Thanks to meth, says Lori, the workers worked and played harder, and she became rich. Within a month, Lori was selling so much Long Beach crank in Ottumwa that she went around her brother-in-law and dealt directly with the middleman in Des Moines. A month after that, she was buying quarter pounds of meth for $2,500 and selling them for $10,000. Unsatisfied with the profit margin, she began dealing directly with the supplier in Long Beach, dispatching Floyd to California once every ten days with instructions to return from the 3,700-mile round-trip with as much meth as he could fit in the trunk of the Corvette Lori had bought him. Lori, meantime, stashed money in the wall of her cabin. Only six months after she had met Floyd’s brother, the wall held $50,000—nearly twice the median yearly income in Ottumwa today.

By the late 1980s, people like Jeffrey William Hayes and Steve Jelinek of Oelwein were buying massive amounts of dope from Lori and establishing their own meth franchises in Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas by selling to the likes of Roland Jarvis, who, yet to start making his own meth, would take what ever he could get in order to work extra shifts at Iowa Ham. Lori, in turn, was dealing directly with what she calls the Mexican Mafia, a somewhat loose group of traffickers who manufactured large amounts of that era’s most powerful dope: P2P. Made predominantly in Long Beach and Orange County, California, in large, clandestine laboratories, this stronger form of meth was more addictive, cheaper, and easier to produce than any other form of the drug available at the time. As such, it increased Lori’s already burgeoning sales manifold.

The so-called Mexican Mafia with whom Lori dealt was built on the vision of two brothers, Jesús and Luís Amezcua, who’d been born in Mexico and lived in San Diego. For years, according to DEA, the Amezcuas had been nothing more than middling cocaine dealers. Until, that is, they perceived the convergence of two seemingly unrelated events. One was that, aided by former pharmaceutical engineers, the Amezcuas could access an enormous, completely legal, and unmonitored supply of the necessary ingredients to make P2P: ephedrine and phenyl-2-propanone. The Amezcuas’ second insight was that they could move large quantities of the drug throughout California and the West, thanks to the increasing numbers of Mexican immigrants who picked fruit in the Central Valley, cleaned homes in Tucson, Arizona, or built roads in Idaho. Furthermore, the brothers could access the Midwest via the ballooning population of Midwesterners who had been chased off their farms, all the way to Southern California.

During the 1980s, large numbers of people from the corn belt left in what sociologists call out-migration. Within the space of just a few years, many Iowa towns, Ottumwa and Oelwein included, lost from 10 to 25 percent of their residents, many of whom headed for the booming labor markets of Los Angeles and San Diego. Family and social connections became business connections as Iowan, Kansan, Dakotan, and Nebraskan laborers in Orange County, eager to get rich, sent loads of the Amezcuas’ meth back home. Or, like Jeffrey William Hayes in Oelwein and Lori Arnold in Ottumwa, either drove out to get it themselves or sent someone in their stead.

Throughout its hundred-year history, meth has been perhaps the only example of a widely consumed illegal narcotic that might be called vocational, as opposed to recreational. The market for meth in America is nearly as old as industrialization. Poor and working-class Americans had been consuming the drug since the 1930s, whether it was marketed as Benzedrine, Methedrine, or Obedrin, for the simple reason that meth makes you feel good and permits you to work hard. Thanks to the Amezcuas and Lori Arnold, these same people no longer needed to rely on expensive prescriptions and were able to get a stronger form of meth at a much better price—this at a time when the drug’s effects were arguably more useful than ever. That’s to say that as meth’s purity rose, its price dropped. So too did meth become much more widely available at exactly the moment that rural economies collapsed and people left. Under those circumstances, says Clay Hallberg, those who remained felt they needed the drug most.

Читать дальше