Chapter 13. Revenge of the Nerds

In the software business there is an ongoing struggle between the pointyheaded academics, and another equally formidable force, the pointy-haired bosses. I believe everyone knows who the pointy-haired boss is. I think most people in the technology world not only recognize this cartoon character, but know the actual person in their company that he is modelled upon.

The pointy-haired boss miraculously combines two qualities that are common by themselves, but rarely seen together: (a) he knows nothing whatsoever about technology, and (b) he has very strong opinions about it.

Suppose, for example, you need to write a piece of software. The pointy-haired boss has no idea how this software has to work and can't tell one programming language from another, and yet he knows what language you should write it in. Exactly. He thinks you should write it in Java.

Why does he think this? Let's take a look inside the brain of the pointy-haired boss. What he's thinking is something like this. Java is a standard. I know it must be, because I read about it in the press all the time. Since it is a standard, I won't get in trouble for using it. And that also means there will always be lots of Java programmers, so if those working for me now quit, as programmers working for me mysteriously always do, I can easily replace them.

Well, this doesn't sound that unreasonable. But it's all based on one unspoken assumption, and that assumption turns out to be false. The pointy-haired boss believes that all programming languages are pretty much equivalent. If that were true, he would be right on target. If languages are all equivalent, sure, use whatever language everyone else is using.

But all languages are not equivalent, and I think I can prove this to you without even getting into the differences between them. If you asked the pointy-haired boss in 1992 what language software should be written in, he would have answered with as little hesitation as he does today. Software should be written in C++. But if languages are all equivalent, why should the pointy-haired boss's opinion ever change? In fact, why should the developers of Java have even bothered to create a new language?

Presumably, if you create anew language, it's because you think it's better in some way than what people already had. And in fact, Gosling makes it clear in the first Java white paper that Java was designed to fix some problems with C++. So there you have it: languages are not all equivalent. If you follow the trail through the pointy-haired boss's brain to Java and then back through Java's history to its origins, you end up holding an idea that contradicts the assumption you started with.

So, who's right? James Gosling, or the pointy-haired boss? Not surprisingly, Gosling is right. Some languages are better, for certain problems, than others. And you know, that raises some interesting questions. Java was designed to be better, for certain problems, than C++. What problems? When is Java better and when is C++? Are there situations where other languages are better than either of them?

Once you start considering this question, you've opened a real can of worms. If the pointy-haired boss had to think about the problem in its full complexity, it would make his head explode. As long as he considers all languages equivalent, all he has to do is choose the one that seems to have the most momentum, and since that's more a question of fashion than technology, even he can probably get the right answer. But if languages vary, he suddenly has to solve two simultaneous equations, trying to find an optimal balance between two things he knows nothing about: the relative suitability of the twenty or so leading languages for the problem he needs to solve, and the odds of finding programmers, libraries, etc. for each. If that's what's on the other side of the door, it is no surprise that the pointy-haired boss doesn't want to open it.

The disadvantage of believing that all programming languages are equivalent is that it's not true. But the advantage is that it makes your life a lot simpler. And I think that's the main reason the idea is so widespread. It is a comfortable idea.

We know that Java must be pretty good, because it is the cool, new programming language. Or is it? If you look at the world of programming languages from a distance, it looks like Java is the latest thing. (From far enough away, all you can see is the large, flashing billboard paid for by Sun.) But if you look at this world up close, you find there are degrees of coolness. Within the hacker subculture, there is another language called Perl that is considered a lot cooler than Java. Slashdot, for example, is generated by Perl. I don't think you would find those guys using Java Server Pages. But there is another, newer language, called Python, whose users tend to look down on Perl, and another called Ruby that some see as the heir apparent of Python.

If you look at these languages in order, Java, Perl, Python, Ruby, you notice an interesting pattern. At least, you notice this pattern if you are a Lisp hacker. Each one is progressively more like Lisp. Python copies even features that many Lisp hackers consider to be mistakes. And if you'd shown people Ruby in 1975 and described it as a dialect of Lisp with syntax, no one would have argued with you. Programming languages have almost caught up with 1958.

13.1. Catching Up with Math

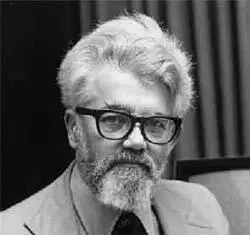

What I mean is that Lisp was first discovered by John McCarthy in 1958, and popular programming languages are only now catching up with the ideas he developed then.

Now, how could that be true? Isn't computer technology something that changes very rapidly? In1958, computers were refrigerator-sized behemoths with the processing power of a wristwatch. How could any technology that old even be relevant, let alone superior to the latest developments?

Figure 13-1. IBM 704, Lawrence Livermore, 1956.

I'll tell you how. It's because Lisp was not really designed to be a programming language, at least not in the sense we mean today. What we mean by a programming language is something we use to tell a computer what to do. McCarthy did eventually intend to develop a programming language in this sense, but the Lisp we actually ended up with was based on something separate that he did as a theoretical exercise—an effort to define a more convenient alternative to the Turing machine. As McCarthy said later,

Another way to show that Lisp was neater than Turing machines was to write a universal Lisp function and show that it is briefer and more comprehensible than the description of a universal Turing machine. This was the Lisp function eval..., which computes the value of a Lisp expression....Writing eval required inventing a notation representing Lisp functions as Lisp data, and such a notation was devised for the purposes of the paper with no thought that it would be used to express Lisp programs in practice.

Figure 13-2. Alpha nerd: John McCarthy.

But in late 1958, Steve Russell, one of McCarthy's grad students, looked at this definition of eval and realized that if he translated it into machine language, the result would be a Lisp interpreter.

This was a big surprise at the time. Here is what McCarthy said about it later:

Steve Russell said, look, why don't I program this eval..., and I said to him, ho,ho, you're confusing theory with practice, this eval is intended for reading, not for computing. But he went ahead and did it. That is, he compiled the eval in my paper into[IBM] 704machine code, fixing bugs, and then advertised this as a Lisp interpreter, which it certainly was. So at that point Lisp had essentially the form that it has today....

Читать дальше