To be an American in the first decade of the twenty-first century was to be present at a grand and fleeting moment, a moment that even if it lasted for several more decades would constitute but a flicker among the long march of hegemons that had calmed broad swaths of the globe. The Persian empires of the Achaemenids and the Sassanids each lasted several hundred years, as did each of five conquering Chinese dynasties, to say nothing of Rome. Byzantium lasted a millennium, as did Venice. Portuguese, Habsburg, Ottoman, and British dominance must be measured in centuries, not decades. Even the Vandal empire of Genseric dominated the Western world’s Mediterranean core for the better part of a hundred years while Rome was collapsing. Because it was a fomenter of dynamic change, a liberal empire like the United States was likely to create the conditions for its own demise, and thus to be particularly short lived.

Some denied the very fact of American empire, claiming a contradiction between an imperial strategy and America’s democratic values. They forgot that Rome, Venice, and Britain were the most morally enlightened states of their age. Venice was defined by a separation of church and state. It had a working constitution which severely limited the authority of its doges, who were unable to act without the approval of their councilors. Its humanistic outlook made Venice the only state of Catholic Europe never to burn a heretic. 22Liberalism at home and a pragmatic, at times ruthless policy abroad have not been uncommon in the history of some empires.

As it happened, the early twenty-first century saw the U.S. in the Second Expeditionary Era regarding its global military-basing posture. 23In the First Expeditionary Era, from the buildup to the Spanish-American War to the end of World War II, the U.S. had established bases in the Caribbean, the Pacific, and the North Atlantic, in order to expand its continental defense perimeter and protect new economic interests. The Cold War years constituted the Garrison Era, in which large, permanent frontier garrisons surrounding the Soviet Union were built in places like West Germany, Turkey, and the Korean Peninsula. The Second Expeditionary Era featured an emphasis on rapid mobility worldwide to deal with peacekeeping interventions, anti-terrorist strikes, and the containment of Iran and Iraq. The post–September 11 global footprint was to put further emphasis on mobility and the dispersion of forces, to deal with the twin threats of radical Islam and the rising power of China.

These strategies were all legacies of Rome, which was constantly requesting territory on foreign soil to build bases. Rome established hardened bases in ungovernable areas for the sake of deterrence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Its superior road network and control of the seas enabled the rapid relocation of its forces in large concentrations at times of crisis. Rome, like Britain, followed a doctrine of “inevitable reversibility.” 24Because it knew that it could not be strong everywhere, that there would be places where it might have to withdraw ignominiously, and other places where it would not be prudent to intervene, Rome emphasized the rapid strategic reaction of its forces rather than their continual presence in too many areas.

———

Just as empires expand by happenstance, impelled forward by a succession of security threats, real or imagined, my journeys also followed no discernible pattern. Friendships with captains and majors helped get me to the most remote locations as much as those with colonels and generals. The American military is a worldwide fraternity. Thus people in one part of the globe led me to another part through the oddest of coincidences. A Coast Guard officer I met in Yemen would stoke my interest in Colombia. An Army officer I met in Mongolia would inform me about Bosnia. An enlisted man in the Philippines told me all about the Singaporean army. The stories themselves were evidence of a global military.

Through it all, I was not truly a war correspondent. I concentrated more on local history and scenery, because the drama of exotic new landscapes has always been central to the imperial experience. A series of books about empire—at least to some degree—had to be about travel.

The number of countries I planned to visit, while considerable, would be less important than the amount of time I spent in the barracks with the troops, and the degree to which I could be accepted by them. I wanted to see the world and their deployments from their perspective, not to judge them from mine. I wanted to devote all of my professional time to this endeavor, for half a decade at least. I wanted to cut myself off from civilians as much as possible. It was the depth and quality of an experience that I was after, particularly with the grunts.

Grunts: cannon fodder. The word best applies to Marine combat infantrymen. But in a sense even Army Special Forces sergeants belonged in the category, because of their willingness to sublimate their own identity to that of the unit. Their concern was less with their own self-preservation than with the preservation of the function they performed. If the man beside you was able to do your job, your own death would matter less. The grunts I met saw themselves as American nationalists, even if the role they performed was imperial.

———

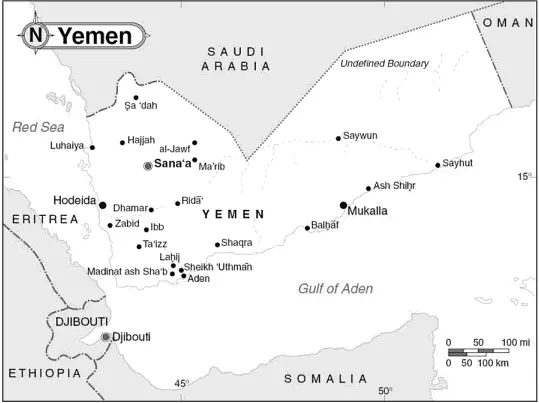

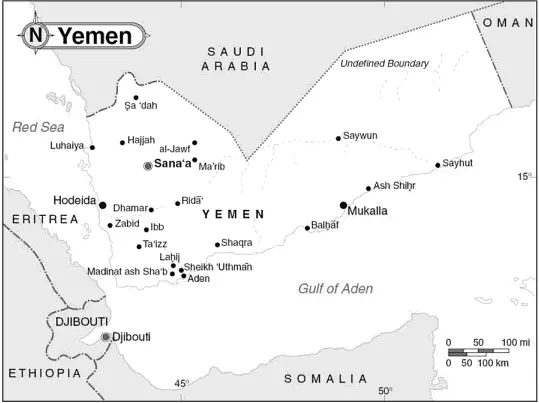

The security threat that had caused the latest and, perhaps, final expansion of the American Empire was especially elusive. More so than infantry phalanxes, there were now clandestine guerrilla cells of young men and occasionally women working to wreak greater destruction than most of the armies of history ever had. Thus I began in Yemen, said at the time to have the largest al-Qaeda presence anywhere outside of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. Yes, Yemen was relatively little known. That was the point. A world empire meant many different places.

But before I linked up with the military, I wanted to scout out America’s latest version of Indian Country by myself: to view at ground level what it was, exactly, that the U.S. was up against. Yemen would constitute merely the long overture to my experience with the troops, rather than the experience itself.

Even in Yemen, though, I would meet an American officer or two: sometimes retired, sometimes working for an international organization, who, in keeping with the implicit nature of American imperialism, like the mountain men and pathfinders of old, was clearing new trails of expansion and influence, in his own indirect and unconscious way.

CHAPTER ONE

CENTCOM

YEMEN, WINTER 2002

WITH NOTES ON COLOMBIA

“Yemen was vast. And it was only one small country…. How to manage such an imperium?”

In November 1934, when the British traveler and Arabist Freya Stark journeyed to Yemen to explore the broad oasis of the Wadi Hadhramaut, the most helpful person she encountered was the French aesthete and business tycoon Antonin Besse, whose Aden-based trading empire stretched from Abyssinia to East Asia. Besse, dressed in a white dinner jacket with creased white shorts, served excellent wine at dinner, and was described as “a Merchant in the style of the Arabian Nights or the Renaissance.” 1In December 2002, when I went to Yemen, the most helpful person I encountered was Bob Adolph, a retired lieutenant colonel in the United States Army Special Forces, who was the United Nations security officer for Yemen.

Adolph, whose military career had taken him all over the world, had the chest of a bodybuilder and a bluff, bulldog face under wire-rim glasses and a creased ball cap. I spotted him on the other side of passport control, waiting in the dusky warehouse under fluorescent lights that functioned as the Sana’a airport.

Читать дальше