Ferenc Puskás was called “Little Cannon Boom” for the smashing virtues of his left leg, which could also catch the ball like a glove. Other Hungarians, Lásló Kubala, Zoltán Czibor, and Sándor Kocsis, were stars with Barcelona in those years. In 1954 the cornerstone was laid for Camp Nou, the great Barcelona stadium built for Kubala: the old stadium could not hold the multitude that came to cheer his precision passes and deadly blasts. Czibor, meanwhile, struck sparks from his shoes. The other Hungarian on Barcelona, Kocsis, was a great header. “Head of Gold,” they called him, and a sea of handkerchiefs celebrated his goals. They say Kocsis had the best head in Europe after Churchill.

Earlier on, in 1950 Kubala had formed a Hungarian team in exile and that earned him a two-year suspension decreed by FIFA. For playing on another exile team after Soviet tanks crushed the popular insurrection at the end of 1956, FIFA suspended Puskás, Czibor, Kocsis, and other Hungarians for more than a year.

In 1958 in the midst of its war of independence, Algeria formed a soccer team, which for the first time wore the national colors. Its line was made up of Rashid Makhloufi, Ben Tifour, and other Algerians who played professionally in France.

Blockaded by the colonial power, Algeria only managed to play against Morocco, which was kicked out of FIFA for several years for committing such a sin, and engage in several unimportant matches organized by sports unions in several Arab and Eastern European countries. FIFA slammed all the doors on the Algerian team, and the French soccer league blacklisted the players. Imprisoned by contracts, they were barred from ever returning to professional activity.

But after Algeria won its independence, the French had no alternative but to call up the players the fans longed for.

In 1916 in the first South American championship, Uruguay creamed Chile 4–0. The next day, the Chilean delegation insisted the match be disallowed “because Uruguay had two Africans in the lineup.” They were Isabelino Gradín and Juan Delgado. Gradín had scored two of the four goals.

Gradín was born in Montevideo, the great-grandson of slaves. He was a man who lifted people out of their seats when he erupted with astonishing speed, dominating the ball as easily as if he were walking. He would drive past the adversaries without a pause and score on the fly. He had a face like the holy host and was one of those guys no one believes when they pretend to be bad.

Juan Delgado, also a great-grandson of slaves, was born in the town of Florida, in the Uruguayan countryside. Delgado liked to show off by dancing with a broom at Carnival and with the ball on the field. He talked while he played, and he liked to tease his opponents: “Pick me that bunch of grapes,” he’d say as he sent the ball high. And as he shot he’d say to the keeper, “Jump for it, the sand is soft.”

Back then Uruguay was the only country in the world with black players on its national team.

He made his first-division debut when he was sixteen, still wearing short pants. Before taking the field with Espanyol in Barcelona, he put on a high-necked English jersey, gloves, and a hard cap like a helmet to protect himself from the sun and other blows. The year was 1917 and the attacks were like cavalry charges. Ricardo Zamora had chosen a perilous career. The only one in greater danger than the goalkeeper was the referee, known at that time as “The Nazarene,” because the fields had no dugouts or fences to protect him from the vengeance of the fans. Each goal gave rise to a long hiatus while people ran onto the field either to embrace or to throw punches.

Over the years the image of Zamora in those clothes became famous. He sowed panic among strikers. If they looked his way they were lost: with Zamora in the goal, the net would shrink and the posts would lose themselves in the distance.

They called him “The Divine One.” For twenty years, he was the best goalkeeper in the world. He liked cognac and smoked three packs a day, plus the occasional cigar.

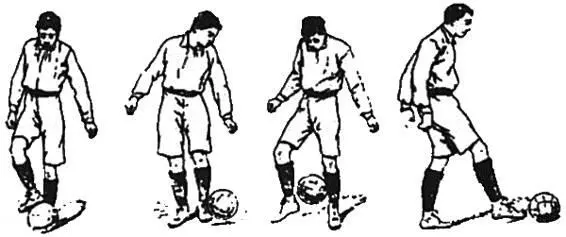

Illustrations from a soccer manual published in Barcelona at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Like Zamora, Josep Samitier made his debut in the first division when he was sixteen. In 1918 he signed with Barcelona in exchange for a watch with a dial that glowed in the dark, something he had never seen, and a suit with a waistcoat.

It wasn’t long before he was the team’s ace and his life story was in kiosks all over the city. His name was on the lips of cabaret singers, bandied about on the stage, and revered in sports columns where they praised the “Mediterranean style” invented by Zamora and Samitier.

Samitier, a striker with a devastating shot, stood out for his cleverness, his domination of the ball, his utter lack of respect for the rules of logic, and his Olympian scorn for the boundaries of space and time.

Abdón Porte, who wore the shirt of the Uruguayan club Nacional for more than two hundred matches over four years, always drew applause and sometimes cheers, until his lucky star fell.

They took him out of the starting lineup. He waited, asked to return, and did. But it was no use; the slump continued, the crowd whistled. On defense even tortoises got past him, on the attack he could not score a single goal.

At the end of the summer of 1918, in the Nacional stadium, Abdón Porte took his own life. He shot himself at midnight at the center of the field where he had been loved. All the lights were out. No one heard the gunshot.

They found him at dawn. In one hand he held a revolver, in the other a letter.

In 1919 Brazil defeated Uruguay 1–0 and crowned itself champion of South America. People flooded the streets of Rio de Janeiro. Leading the celebration, raised aloft like a standard, was a muddy soccer boot with a little sign that proclaimed: “The glorious foot of Friedenreich.” The next day that shoe, which had scored the winning goal, ended up in the display window of a downtown jewelry shop.

Artur Friedenreich, son of a German immigrant and a black washerwoman, played in the first division for twenty-six years and never earned a cent. No one scored more goals than he in the history of soccer, not even that other great Brazilian artilleryman, Pelé, who remains professional soccer’s leading scorer. Friedenreich converted 1,329, Pelé 1,279.

Читать дальше