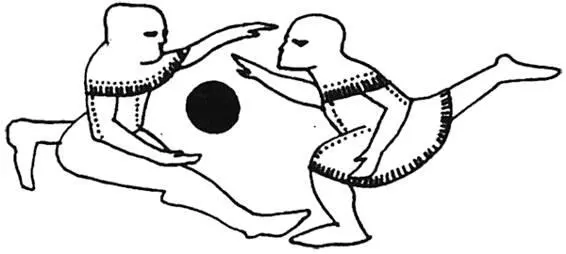

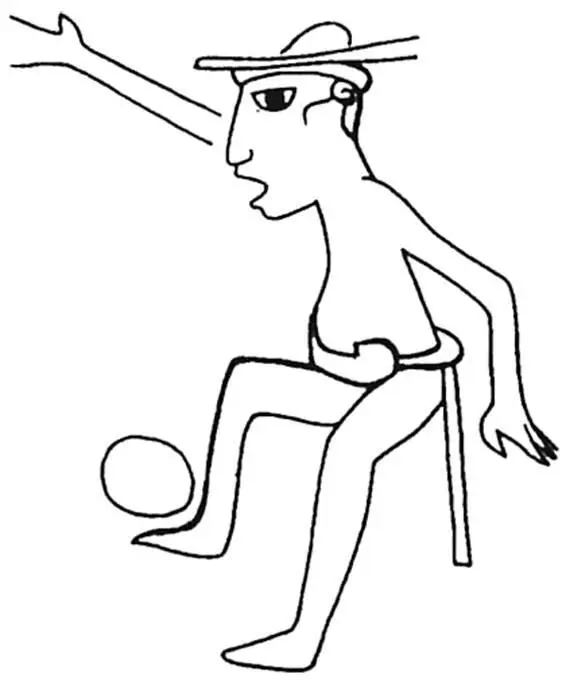

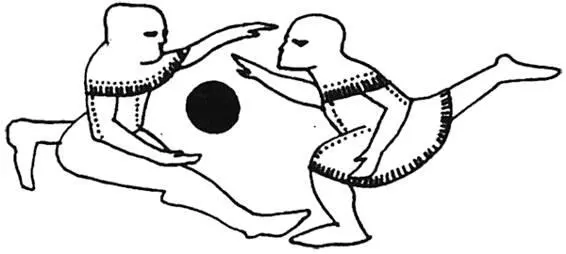

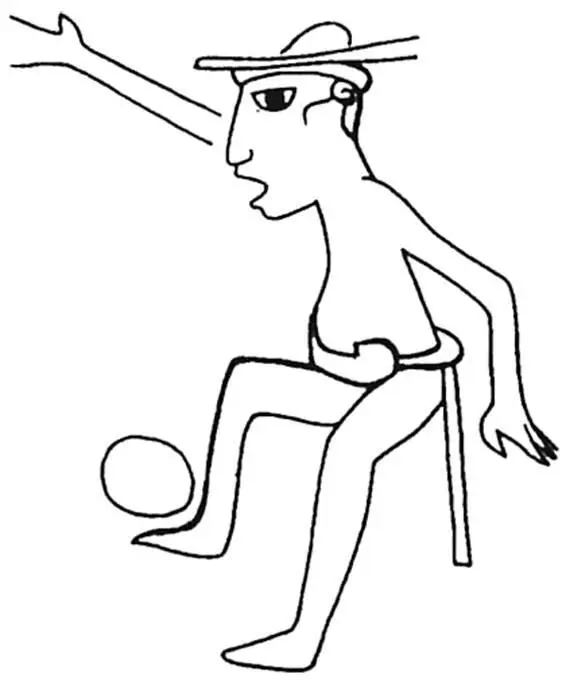

Two historical images. The first is from a fragment of a mural painted over a thousand years ago in Tepantitla at Teotihuacán, Mexico: Hugo Sánchez’s ancestor maneuvering the ball with his left. The second is a stylized drawing of a medieval relief from the cathedral at Gloucester, England.

In soccer, as in almost everything else, the Chinese were first. Five thousand years ago, Chinese jugglers had balls dancing on their feet, and it wasn’t long before they organized the first matches. The net stood in the center of the field and the players had to keep the ball from touching the ground without using their hands. The sport continued from dynasty to dynasty, as can be seen on certain bas-relief monuments from long before Christ and in later Ming Dynasty engravings, which show people playing with a ball that could have been made by Adidas.

We know that in ancient times the Egyptians and the Japanese had fun kicking a ball around. On the marble surface of a Greek tomb from five centuries before Christ a man is kneeing a ball. The plays of Antiphanes contain telling expressions like “long ball,” “short pass,” and “forward pass.” They say that Julius Caesar was quick with his feet, and that Nero couldn’t score. In any case, there is no doubt that while Jesus was dying on the cross the Romans were playing something fairly similar to soccer.

Roman legionaries kicked the ball all the way to the British Isles. Centuries later, in 1314, King Edward II stamped his seal on a royal decree condemning the game as plebeian and riotous: “Forasmuch as there is a great noise in the city caused by hustling over large balls, from which many evils may arise, which God forbid.” Football, as it was already being called, left a slew of victims. Matches were fought in gangs, and there were no limits on the number of players, the length of the match, or anything else. An entire town would play against another town, advancing with kicks and punches toward the goal, which at that time was a far-off windmill. The matches extended over several leagues and several days at the cost of several lives. Kings repeatedly outlawed these bloody events: in 1349, Edward III included soccer among games that were “stupid and utterly useless,” and there were edicts against the sport signed by Henry IV in 1410 and Henry VI in 1447. The more it was banned, the more it was played, which only confirms that prohibition whets the appetite.

In 1592 in The Comedy of Errors , Shakespeare turned to soccer to formulate a character’s complaint:

Am I so round with you as you with me,

That like a football you do spurn me thus?

You spurn me hence, and he will spurn me hither:

If I last in this service, you must case me in leather.

And a few years later in King Lear , the Earl of Kent taunted: “Nor tripped neither, you base football player!”

In Florence soccer was called calcio , as it is even now throughout Italy. Leonardo da Vinci was a fervent fan and Machiavelli loved to play. It was played in sides of twenty-seven men split into three lines, and they were allowed to use their hands and feet to hit the ball and gouge the bellies of their adversaries. Throngs of people attended the matches, which were held in the largest piazzas and on the frozen waters of the Arno. Far from Florence, in the gardens of the Vatican, Popes Clement VII, Leo IX, and Urban VIII used to roll up their vestments to play calcio .

In Mexico and Central America a rubber ball filled in for the sun in a sacred ceremony performed as far back as 1500 B.C. But we do not know when soccer began in many places of the Americas. The Indians of the Bolivian Amazon say they have been chasing a hefty rubber ball to put it between two posts without using their hands since time immemorial. In the eighteenth century, a Spanish priest from the Jesuit missions of the Upper Paraná described an ancient custom of the Guarani: “They do not throw the ball with their hands like us, rather they propel it with the upper part of their bare foot.” Among the Indians of Mexico and Central America, the ball was generally hit with the hip or the forearm, although paintings at Teotihuacán and Chichén-Itzá show the ball being kicked with the foot and the knee. A mural created over a thousand years ago in Tepantitla has an ancestor of Hugo Sánchez maneuvering the ball with his left. The match would end when the ball approached its destination: the sun arrived at dawn after traveling through the region of death. Then, for the sun to rise, blood would flow. According to some in the know, the Aztecs were in the habit of sacrificing the winners. Before cutting off their heads, they painted red stripes on their bodies. The chosen of the gods would offer their blood, so the earth would be fertile and the heavens generous.

After centuries of official denial, the British Isles finally accepted the ball in its destiny. Under Queen Victoria soccer was embraced not only as a plebeian vice but as an aristocratic virtue.

The future leaders of society learned how to win by playing soccer in the courtyards of colleges and universities. There, upper-class brats unbosomed their youthful ardors, honed their discipline, tempered their anger, and sharpened their wits. At the other end of the social scale, workers had no need to test the limits of their bodies, since that is what factories and workshops were for, but the fatherland of industrial capitalism discovered that soccer, passion of the masses, offered entertainment and consolation to the poor and distraction from thoughts of strikes and other evils.

In its modern form, soccer comes from a gentleman’s agreement signed by twelve English clubs in the autumn of 1863 in a London tavern. The clubs agreed to abide by rules established in 1848 at the University of Cambridge. In Cambridge soccer divorced rugby: carrying the ball with your hands was outlawed, although touching it was allowed, and kicking the adversary was also prohibited. “Kicks must be aimed only at the ball,” warned one rule. A century and a half later some players still confuse the ball with their rival’s skull owing to the similarity in shape.

The London accord put no limit on the number of players, or the size of the field, or the height of the goal, or the length of the contest. Matches lasted two or three hours and the protagonists chatted and smoked whenever the ball was flying in the distance. One modern rule was established: the offside. It was disloyal to score goals behind the adversary’s back.

In those days no one played a particular position on the field. They all ran happily after the ball, each wherever he wanted, and everyone changed positions at will. It fell to Scotland around 1870 to organize teams with defense, midfielders, and strikers. By then sides had eleven players. From 1869 on, none of them could touch the ball with his hands, not even to catch and drop it to kick. In 1871 the exception to that taboo was born: the goalkeeper could use his entire body to defend the goal.

Читать дальше