In soccer, ritual sublimation of war, eleven men in shorts are the sword of the neighborhood, the city, or the nation. These warriors without weapons or armor exorcise the demons of the crowd and reaffirm its faith: in each confrontation between two sides, old hatreds and old loves passed from father to son enter into combat.

The stadium has towers and banners like a castle, as well as a deep and wide moat around the field. In the middle, a white line separates the territories in dispute. At each end stand the goals to be bombed with flying balls. The area directly in front of the goals is called the “danger zone.”

In the center circle, the captains exchange pennants and shake hands as the ritual demands. The referee blows his whistle and the ball, another whistling wind, is set in motion. The ball travels back and forth, a player traps her and takes her for a ride until he gets pummeled in a tackle and falls spread-eagled. The victim does not rise. In the immensity of the green expanse, the player lies prostrate. From the immensity of the stands, voices thunder. The enemy crowd emits a friendly roar:

“¡Que se muera!”

“Devi morire!”

“Tuez-le!”

“Mach ihn nieder!”

“Let him die!”

“Kill, kill, kill!”

Utilizing a competent tactical variant of their planned strategy, our squad leaped to the charge, surprising the enemy unprepared. It was a brutal attack. When the home troops invaded enemy territory, our battering ram opened a breach in the most vulnerable flank of the defensive wall and infiltrated the danger zone. The artilleryman received the projectile and with a skillful maneuver he got into shooting position, reared back for the kill, and brought the offensive to culmination with a cannonball that annihilated the guard. Then the defeated sentry, custodian of the seemingly unassailable bastion, fell to his knees with his face in his hands, while the executioner who shot him raised his arms to the cheering crowd.

The enemy did not retreat, but its stampedes never managed to sow panic in the home trenches, and time and again they crashed against our well-armored rear guard. Their men were shooting with wet powder, reduced to impotence by the gallantry of our gladiators, who battled like lions. When two of ours were knocked out of the fight, the crowd called in vain for the maximum sentence, but such atrocities fit for war and disrespectful of the gentlemanly rules of the noble sport of soccer continued with impunity.

At last, when the deaf and blind referee called an end to the contest, a well-deserved whistle discharged the defeated squad. Then the victorious throngs invaded the redoubt to hoist on their shoulders the eleven heroes of this epic gest, this grand feat, this great exploit that cost so much blood, sweat, and tears. And our captain, wrapped in the standard of our fatherland that will never again be soiled by defeat, raised up the trophy and kissed the great silver cup. It was the kiss of glory!

Have you ever entered an empty stadium? Try it. Stand in the middle of the field and listen. There is nothing less empty than an empty stadium. There is nothing less mute than stands bereft of spectators.

At Wembley shouts from the 1966 World Cup, which England won, still resound, and if you listen very closely you can hear groans from 1953, when England fell to the Hungarians. Montevideo’s Centenario Stadium sighs with nostalgia for the glory days of Uruguayan soccer. Maracanã is still crying over Brazil’s 1950 World Cup defeat. At Bombonera in Buenos Aires, drums boom from half a century ago. From the depths of Azteca Stadium, you can hear the ceremonial chants of the ancient Mexican ball game. The concrete terraces of Camp Nou in Barcelona speak Catalan, and the stands of San Mamés in Bilbao talk in Basque. In Milan, the ghost of Giuseppe Meazza scores goals that shake the stadium bearing his name. The final match of the 1974 World Cup, won by Germany, is played day after day and night after night at Munich’s Olympic Stadium. King Fahd Stadium in Saudi Arabia has marble and gold boxes and carpeted stands, but it has no memory or much of anything to say.

The Chinese used a ball made of leather and filled with hemp. In the time of the Pharaohs the Egyptians used a ball made of straw or the husks of seeds, wrapped in colorful fabric. The Greeks and Romans used an ox bladder, inflated and sewn shut. Europeans of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance played with an oval-shaped ball filled with horsehair. In America the ball was made of rubber and bounced like nowhere else. The chroniclers of the Spanish Court tell how Hernán Cortés bounced a Mexican ball high in the air before the bulging eyes of Emperor Charles.

The rubber chamber, swollen with air and covered with leather, was born in the middle of the nineteenth century thanks to the genius of Charles Goodyear, an American from Connecticut. And long after that, thanks to the genius of Tossolini, Valbonesi, and Polo, three Argentines from Córdoba, the lace-free ball was born. They invented a chamber with a valve inflated by injection, and ever since the 1938 World Cup it has been possible to head the ball without getting hurt by the laces that once tied it together.

Until the middle of the twentieth century, the ball was brown. Then white. In our days it comes in different patterns of black on a white background. Now it has a waist of sixty centimeters and is dressed in polyurethane on polyethylene foam. Waterproof, it weighs less than a pound and travels more quickly than the old leather ball, which on rainy days barely moved.

They call it by many names: the sphere, the round, the tool, the globe, the balloon, the projectile. In Brazil no one doubts the ball is a woman. Brazilians call her pudgy, gorduchinha , or baby, menina , and they give her names like Maricota, Leonor, or Margarita.

Pelé kissed her in Maracanã when he scored his thousandth goal and Di Stéfano built her a monument in front of his house, a bronze ball with a plaque that says: Thanks, old girl .

She is loyal. In the final match of the 1930 World Cup, both teams insisted on playing with their own ball. Sage as Solomon, the referee decided that the first half would be played with the Argentine ball and the second with the Uruguayan ball. Argentina won the first half, and Uruguay the second. The ball can also be fickle, refusing to enter the goal because she changes her mind in midflight and curls away. You see, she is easily offended. She cannot stand getting kicked or hit out of spite. She insists on being caressed, kissed, lulled to sleep on the chest or the foot. She is proud, vain perhaps, and it is easy to understand why: she knows all too well that when she rises gracefully she brings joy to many a heart, and many a heart is crushed when she lands badly.

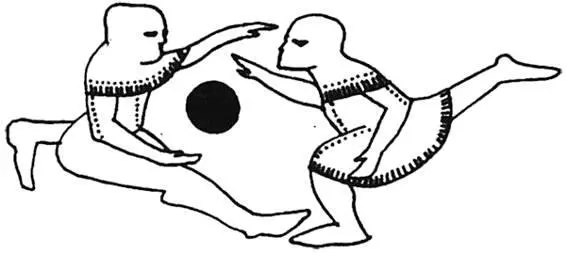

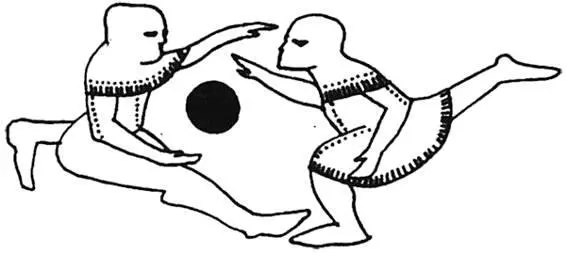

This Ming Dynasty engraving is from the fifteenth century, but the ball could have been made by Adidas.

Читать дальше