As 1992 unfolded, Yugoslavia fell to pieces. War taught brothers to hate each other, and to kill and rape without remorse.

Two Mexican journalists, Epi Ibarra and Hernán Vera, wanted to go to Sarajevo. Bombarded, under siege, Sarajevo was off-limits to the foreign press, and recklessness had already cost more than one reporter his life.

Chaos reigned on all approaches to the city. Everyone against everyone else: no one was sure who was who, or who they were fighting in that bedlam of trenches, smoking ruins, and unburied bodies. Map in hand, Epi and Hernán made their way through the thunder of artillery-fire and machine-gun blasts, until on the banks of the Drina River they suddenly came face-to-face with a large group of soldiers who threw them to the ground and took aim at their chests. The officer bellowed who knows what and the reporters mumbled back who knows what else, but when the officer drew his finger across his throat and the rifles went click, they understood that there was nothing left to do but say good-bye and pray, just in case there is a heaven.

Then it occurred to the condemned men to show their passports. The officer’s face lit up. “Mexico!” he screamed. “Hugo Sánchez!”

And he dropped his weapon and hugged them.

Hugo Sánchez, the Mexican key to impossible locks, became world famous thanks to television, which showcased the art of his goals and the handsprings he turned to celebrate them. In the 1989–1990 season, wearing the uniform of Real Madrid, he burst the nets thirty-eight times and became the leading foreign scorer in the entire history of Spanish soccer.

In 1992 the singing cricket defeated the worker ant 2–0.

Germany and Denmark faced each other in the final of the European Championship. The German players were raised on fasting, abstinence, and hard work, the Danes on beer, women, and naps in the sun. Denmark had lost out in the qualifiers and the players were on vacation when war intervened and they got an urgent call to take Yugoslavia’s place in the tournament. They had no time for training nor any interest in it, and had to make do without their most brilliant star, Michael Laudrup, a happy and sure-footed player who had just won the European Cup wearing a Barcelona shirt. The German team, on the other hand, came to the final with Matthäus, Klinsmann, and all of its other big guns. Germany, which should have won, were defeated by Denmark, which had nothing to prove and played as if the field were a continuation of the beach.

In 1993 a tide of racism was rising. Its stench, like a recurring nightmare, already hung over Europe; several crimes were committed and laws to keep out ex-colonial immigrants were passed. Many young whites, unable to find work, began to blame their plight on people with dark skin.

That year a team from France won the European Cup for the first time. The winning goal was the work of Basile Boli, an African from the Ivory Coast, who headed in a corner kicked by another African, Abedi Pele, who was born in Ghana. Meanwhile, not even the blindest proponents of white supremacy could deny that the Netherlands’ best players were the veterans Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard, dark-skinned sons of Surinamese parents, or that the African Eusébio had been Portugal’s best soccer player ever.

Ruud Gullit, known as “The Black Tulip,” had always been a full-throated opponent of racism. Guitar in hand, he sang at anti-apartheid concerts between matches, and in 1987, when he was chosen Europe’s most valuable player, he dedicated his Ballon d’Or to Nelson Mandela, who spent many years in jail for the crime of believing that blacks are human.

One of Gullit’s knees was operated on three times. Each time commentators declared he was finished. Out of sheer desire he always came back: “When I can’t play I’m like a newborn with nothing to suck.”

His nimble scoring legs and his imposing stature crowned by a head of Rasta dreadlocks won him a fervent following when he played for the strongest teams in the Netherlands and Italy. But Gullit never got along with coaches or managers because he tended to disobey orders, and he had the stubborn habit of speaking out against the culture of money that is reducing soccer to just another listing on the stock exchange.

At the end of the southern winter of 1993, Colombia’s national team played a World Cup qualifier in Buenos Aires. When the Colombian players took the field, they were greeted with a shower of whistles, boos, and insults. When they left, the crowd gave them a standing ovation that echoes to this day.

Argentina lost 5–0. As usual, the goalkeeper carried the cross of the defeat, but this time the visitors’ victory was celebrated as never before. To a one, the fans cheered the Colombians’ incredible style, a feast of legs, a joy for the eyes, an ever-changing dance that invented its own music as the match progressed. The lordly play of “El Pibe” Balderrama, a working-class mulatto, was the envy of princes, and the black players were the kings of this carnival: not a soul could get past Perea or stop “Freight Train” Valencia; not a soul could deal with the tentacles of “Octopus” Asprilla or block the bullets fired by Rincón. Given the color of their skin and the intensity of their joy, those Colombians looked like Brazil in its glory years.

The Colombian press called the massacre a “parricide.” Half a century before, the founding fathers of soccer in Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali were Argentines. But life has its surprises: Pedernera, Di Stéfano, Rossi, Rial, Pontoni, and Moreno fathered a child who turned out to be Brazilian.

It was 1993. In Tokyo, Kashima was playing Tohoku for the Emperor’s Cup.

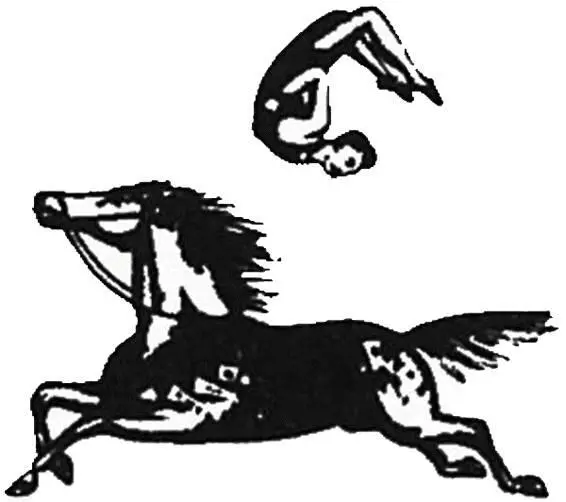

The Brazilian Zico, star of Kashima, scored the winning goal, the loveliest of his career. The ball reached the center on a cross from the right. Zico, who was in the semicircle, leaped forward. But he jumped too soon. When he realized the ball was behind him, he turned a somersault in midair and with his face to the ground he drove it in with his heel. It was a backward overhead volley.

“Tell me about that goal,” plead the blind.

When Spain was still suffering under the Franco dictatorship, Real Madrid president Santiago Bernabéu set out a definition of the club’s mission: “We are serving the nation. What we want is to make people happy.”

His colleague from Atlético de Madrid, Vicente Calderón, also praised the sport’s virtues as a collective Valium: “Soccer keeps people from thinking about more dangerous things.”

Читать дальше