• • •

WAHHABISMis a modern fundamentalist movement in Islam, and in the late 1990s its presence was beginning to be felt in the Caucasus. The war in Chechnya, which began with Moscow’s crackdown on a secular ethnic self-determination movement, had changed Chechen society profoundly. Hundreds of thousands of Chechens had been killed or had left during the armed conflict from 1994 to 1996. When a peace treaty was finally signed in August 1996, giving Chechnya essentially the autonomy it had been seeking but without the official status of an independent state, its population had been depleted, its earth had been scorched, and its economy had been destroyed. Its leader, Dzhokhar Dudaev, had been killed by a targeted Russian missile in April of that year. He was replaced with Aslan Maskhadov, who had been his right hand. Maskhadov was very much in the Dudaev mold, also a former officer in the Soviet army, also entirely secular and assimilated, but he lacked Dudaev’s ruthless charisma, and by the time he signed the peace treaty with Moscow he lacked full authority over Chechen rebel fighters.

In the desperate years that followed, radicalism of every sort flourished. A small number of proselytizers from Saudi Arabia and other countries found a large number of young men willing to listen to them, and to begin proudly calling themselves Wahhabis. They believed another war was in the offing; Russia remained the enemy, but the soldiers’ new fervor was religious rather than ethnic. For several years they fought a guerrilla war that looked more like a number of gangs preying on vulnerable people under the guise of a holy war: they kidnapped journalists, foreign humanitarian workers, and even Chechens; some of the hostages were killed and others released for ransom. Then another war really did begin.

In the summer of 1999, armed Chechen fighters began crossing over into neighboring Dagestan. In August and September 1999, Russia was terrorized by a series of apartment-building explosions that killed more than three hundred people. Russia’s newly appointed prime minister and Yeltsin’s anointed successor, the former KGB colonel Vladimir Putin, blamed these bombings on Chechens, linked the acts of terror to the new Chechen armed presence in Dagestan, and unleashed the Russian military on Chechens in both Chechnya and Dagestan. The new war, which would drag on for years, catapulted the previously unknown Putin to national popularity, ensuring he would indeed become Russia’s next president. In the years after the start of the second war, a wealth of evidence emerged pointing to Russian secret-police involvement in both the apartment-building bombings and the Dagestan incursions, but with Putin quickly turning Russia into an authoritarian state, this evidence never became the object of official investigation. Journalists, politicians, and activists who tried to conduct their own investigations were assassinated.

Dagestan, meanwhile, found itself in the middle of a war. In response, local authorities did something that essentially ensured the war would go on for years to come and the supply of soldiers would be limitless: they outlawed Wahhabism, by which they also understood Salafism. The urban young men whose conflict had been with their own fathers and their village elders were now, dangerously and romantically, outlaws. Their everyday religious practices were forced underground: even the imams of Makhachkala’s two large Salafite mosques took to pretending they were Sufis.

The local police and the federal troops now stationed in Dagestan soon settled on a singular, and singularly ineffective, tactic for fighting the enemy they had conjured—a witch hunt. Local authorities compiled lists of suspected Wahhabis. A young man could land on the list for wearing a beard, for attending the wrong mosque, or for no reason at all. Men whose names were on the list were detained, interrogated—in a couple of years some would report being asked, “Where were you on September 11, 2001?”—and, in the best-case scenario, released only to face further harassment. In the worst case, they disappeared.

In response, some of the young men took up grenades, mines, and bombs. These were most often used to blow up police vehicles. Makhachkala and much of the rest of Dagestan became a battleground, with explosions and gunfights erupting daily. This was the Dagestan to which Anzor and Zubeidat brought their four children, including Tamerlan, who at fourteen was on the verge of becoming that most endangered and most dangerous of humans: a young Dagestani man. Anzor and Zubeidat had to move again, to save their children—again.

They would go to America after all.

PART TWO

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BECOMING THE BOMBERS

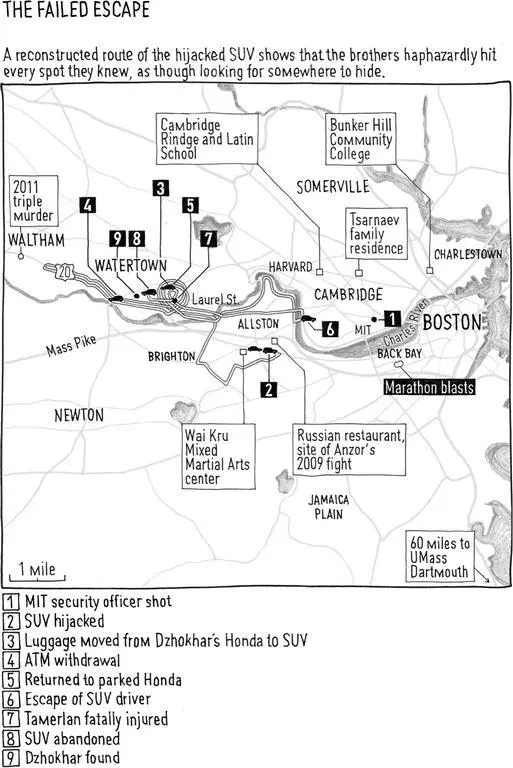

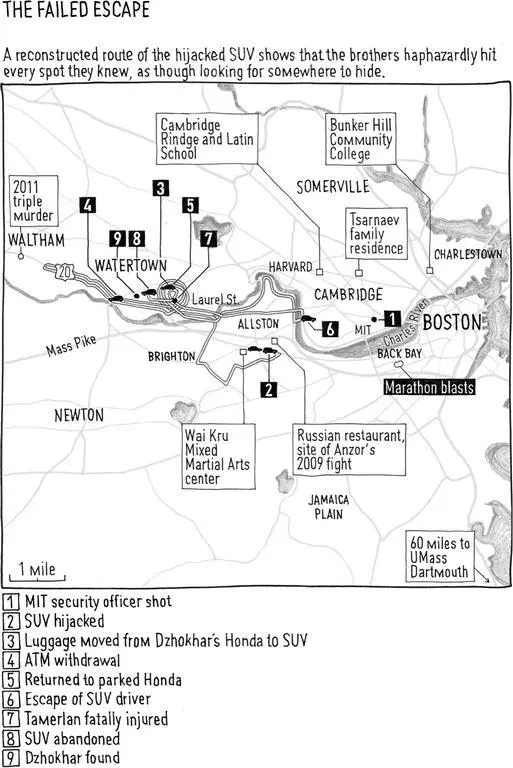

Visit http://bit.ly/brothersmap2for a larger version of this map.

Many media accounts of the Tsarnaev story have hinted or simply stated that they lied to get into the United States, that they never should have been granted asylum—indeed, that had the asylum process worked as it should, weeding the worthy victims from the dangerous ones, a tragedy could have been averted. In fact, the Tsarnaevs typified asylum seekers in America, and the process in their case worked as well, or as poorly, as it does the vast majority of the time. Future asylum seekers usually come to the United States on visitors’ visas and then, relying on a network of family and friends, try to make ends meet, not quite legally, while they apply for asylum. And yes, they usually lie, or at least embellish.

Making your case to the immigration authorities is different from making a case in court: rather than tell a coherent story, you, the asylum seeker, tell of everything that has gone wrong in your life—at least the things that went wrong that the asylum officer might find worthy of notice. You exaggerate, you mold your story to fit the requirements. It probably would not work to tell the officer that you were born in a country where you could never be a full citizen, a country that then broke apart into several others, which you crisscrossed trying to find a home and could not, and so you came to America. Instead, you have to say that you have been subjected to persecution based on your ethnic origin and you are fleeing a war. The Tsarnaevs did just that: they relied on the war in Chechnya and the ethnic discrimination in Kyrgyzstan to establish their credentials. Anzor appears to have claimed that he was briefly jailed and tortured in Kyrgyzstan as part of a broad anti-Chechen crackdown. He may indeed have been detained in Kyrgyzstan toward the end of his time there, though this was most likely to have been connected to his work for Jamal’s business. It would have been much too complicated to try to explain to an asylum officer that the Chechens’ very existence on the permanent wrong side of the law in Kyrgyzstan and elsewhere was a function of generations of disenfranchisement. Anzor could be said to have used shorthand.

• • •

THE TWO CHECHEN WARS,the one in the mid-1990s and the one that began in 1999, displaced hundreds of thousands of people. Many of them stayed in the former Soviet Union, joining relatives in Central Asia or Russia. Tens of thousands sought refuge in countries of the European Union, where they often spent years in refugee camps. Very few made it all the way to the United States. The people who came were not always the ones who most needed to escape: they were the ones most capable of escaping. “With any country early on in a conflict, the people who claim asylum first are usually the elites or people who don’t actually live there,” says Almut Rochowanski, a Columbia University legal scholar who in the early 2000s started an organization that helped new Chechen refugees find legal representation, although she herself was born in Austria and had no personal connection to Chechnya until research and human rights work took her there. The first Chechen refugees to arrive in the United States were members of the Dudaev pro-independence government and Chechens from Central Asia. Later came the people whose family members had been disappeared by the Russian authorities or the Chechen fighters. In refugee camps and in tiny Chechen communities that formed abroad, they often mixed with people who had actually been fighters—making for messy alliances at best and open conflict at worst.

Читать дальше