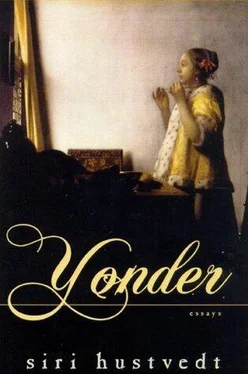

Conception and pregnancy — that’s what the Annunciation is about, after all — an explanation of the divine presence inside a human being. Natural pregnancy and its role in Dutch painting is an old dispute, and it pops up again with Vermeer, although not in regard to the woman with the pearls. Albert Blankert writes that van Gogh was the first person to suggest that the Woman in Blue Reading a Letter is pregnant and points out that the belly of Vermeer’s virgin goddess Diana “looks thoroughly bulbous to twentieth century eyes” as well. 4My personal response to this is that Diana doesn’t look nearly as pregnant as the woman in blue, who appears to be on the brink of giving birth. No doubt the fashion of the day promoted the big belly as a sign of beauty, but this protruding belly must have been regarded as beautiful for the very reason that it mimicked pregnancy. When he died at forty-two, Vermeer left ten minor children. Obviously, pregnancies came and went at a rapid clip in his own household, and he must have had intimate knowledge of pregnancy in all its stages. Vermeer’s attention to the physical detail of domestic life and to the women who inhabit it would necessarily have included the changing shape of women themselves. How could it not?

Neither her body nor her clothes tell us whether the woman with the necklace is pregnant. The hint of her pregnancy is in the painting’s relation to the Annunciation, to a miraculous beginning. It is in her gaze and in the luster of the pearls themselves, which signify, among other things, purity and virginity. It is in her unmoving fingers that call to mind the nearly uncanny quiet of physical gesture in early Renaissance paintings — in which the human body not only speaks for itself but also articulates the codes of religious experience. The truth is, however, that the whole painting conveys enclosure and privacy. The room, with its closed window and single, egg-shaped detail, and the rotund covered jar in the foreground that blends with the vast piece of cloth, are all lit by the enchanted light that comes from beyond the room. We are allowed to look at a world sufficient unto itself, a world that is lit by the holiness of an everyday miracle — pregnancy and birth — perceived in the painting as a gift from God, shining in God’s light, which is also real light, the light of day. The magic here is of being itself, never more fully experienced than in pregnancy — two people in one body. Isn’t this why the woman communicates no desire — only completeness — and why the light seems to hold her as much as the mirror?

Nevertheless, I want to emphasize that my reading is not meant to reduce the painting to an Annunciation either. Vermeer brought the miraculous into a room just like the rooms he knew, and he endowed the features of an ordinary woman with spiritual greatness. Woman with a Pearl Necklace is a painting that makes no distinction between the physical and the spiritual world. Here they are inseparable. Each merges within the other to form a totality. In Vermeer, the gulf between the symbol and the real is closed. Woman with a Pearl Necklace is a work of reflection at its most sublime. The viewer reflects on the woman, who also reflects and is reflected, and through this mirroring of wonder, Vermeer elevates not only his creature — the woman in the painting — but all of us who look at her — because looking at her and the memory of looking at her become nothing less than an affirmation of the strangeness and beauty of simply being alive.

I first read The Great Gatsby when I was sixteen years old, a high school student in Northfield, Minnesota. I read it again when I was twenty-three and living in New York City, and now again at the advanced age of forty-two. I have carried the book’s magic around with me ever since that first reading, and its memory is distinct in my mind, because unlike many books that return to me chiefly as a series of images, The Great Gatsby has also left its trace in my ear — as enchanted music, whispering, laughter, and as the voice of storytelling itself.

The book begins with the narrator’s memory of something his father told him years before: “Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone, remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” As an adage for life, the quotation is anticlimactic — restrained words I imagine being uttered by a restrained man, perhaps over the top of his newspaper, and yet without this watered-down American version of noblesse oblige, there could be no story of Gatsby. The father’s words are the story’s seed, its origin. The man who we come to know as Nick Carraway tells us that his father “meant a great deal more” than what the words denote, and I believe him. Hidden in the comment is a way of living and an entire moral world. Its resonance is double: first, we know that the narrator’s words are bound to his father’s words, that he comes from somewhere he can identify, and that he has not severed that connection; and second, that these paternal words have shaped him into who he is: a man “inclined to reserve all judgements”—in short, the ideal narrator, a man who doesn’t leap into the action but stays on the sidelines. Nick is not an actor but a voyeur, and in every art, including the art of fiction, there’s always somebody watching.

Taking little more than his father’s advice, the young man goes east. The American story has changed direction: the frontier is flip-flopped from west to east, but the urge to leave home and seek your fortune is as old as fairy tales. Fitzgerald’s Middle West was not the same as mine. I did not come from the stolid advantages of Summit Avenue in St. Paul. I remember those large, beautiful houses on that street as beacons of wealth and privilege to which I had no access. I grew up in the open spaces of southern Minnesota in one of the “lost Swede towns” Fitzgerald mentions late in the book, only we were mostly Norwegians, not Swedes. It was to my hometown that Fitzgerald sent Gatsby to college for two weeks. The unnamed town is Northfield. The named college is St. Olaf, where my father taught for thirty years and where I was a student for four. Gatsby’s ghost may have haunted me, because even in high school, I knew that promise lay in the East, particularly in New York City, and ever so vaguely, I began to dream of what I had never seen and where I had never been.

Nick Carraway hops a train and finds himself in the bond trade and living next door to Gatsby’s huge mansion: a house built of wishes. All wishes, however wrongheaded, however great or noble or ephemeral, must have an object, and that object is usually more ideal than real. The nature of Gatsby’s wish is fully articulated in the book. Gatsby is great, because his dream is all-consuming and every bit of his strength and breath are in it. He is a creature of will, and the beauty of his will overreaches the tawdriness of his real object: Daisy. But the secret of the story is that there is no great Gatsby without Nick Carraway, only Gatsby, because Nick is the only one who is able to see the greatness of his wish.

Reading the book again, I was struck by the strangeness of a single sentence that seemed to glitter like a golden key to the story. It occurs when a dazed Gatsby finds his wish granted, and he is showing Daisy around the West Egg mansion. Nick is, as always, the third wheel. “I tried to go then,” he says, “but they wouldn’t hear of it; perhaps my presence made them feel more satisfactorily alone.” The question is: In what way are two people more satisfactorily alone when somebody else is present? What on earth does this mean? I have always felt that there is a triangular quality to every love affair. There are two lovers and a third element — the idea of being in love itself. I wonder if it is possible to fall in love without this third presence, an imaginary witness to love as a thing of wonder, cast in the glow of our deepest stories about ourselves. It is as if Nick’s eyes satisfy this third element, as if he embodies for the lovers the essential self-consciousness of love — a third-person account. When I read Charles Scribner III’s introduction to my paperback edition, I was not at all surprised that an early draft of the novel was written by Fitzgerald in the third person. Lowering the narration into the voice of a character inside the story allows the writer to inhabit more fully the interstices of narrative itself.

Читать дальше