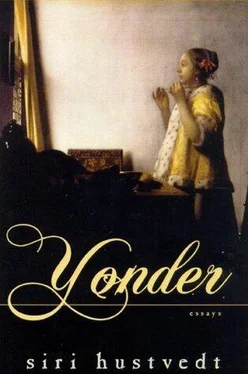

So what’s happening in this room? The woman trying on her necklace is young, pretty, and beautifully dressed, but she is not preening in front of her reflection. Nothing about her expression or posture suggests vanity. On the table, it is possible to see part of a bowl and a powder brush, but these objects, even if she has recently used them, are forgotten things. They are pulled into the shadow of the dark foreground, which forbids entrance and makes the empty space of light between the woman and mirror more dramatic. While I was looking at the painting, I realized that I had picked it because of its empty center, a quality that distinguished it from other, related works. The painting was hanging in a room with three other great Vermeer paintings of women alone: Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, and Woman Holding a Balance. In all of these paintings, women occupy a space that is illuminated by a far window on the left as you face the canvas (although the window in Woman in Blue is implied, rather than depicted, by the source of light that illuminates her page). In the three other paintings there is a map or painting somewhere on the wall in the room. In Woman with a Pearl Necklace there is nothing but light.

It turns out that Vermeer changed his mind. Arthur Wheelock, in his short essay on the painting in the catalog, which I read fitfully while I was in the museum, writes that neutron autoradiography of the canvas shows that there was once a map on that shining wall and, moreover, a musical instrument, probably a lute, sitting on the chair. The great folds of cloth in the foreground also covered considerably less of the tile floor. By simplifying the painting, by allowing fewer elements to remain, Vermeer altered the work’s effect and meaning forever. The map, which can be seen in the neutron autoradiograph reproduced in the catalog, was located behind the woman’s upper body, and even in the small and foggy picture in the catalog, the map draws the viewer back to the wall and gives that surface greater dimension and flatness. By eliminating the map, Vermeer got rid of an object that would have made a geometric cut between the woman’s eyes and the window. The map would have interrupted the line of her gaze and disturbed its directness. And had it remained, it would inevitably have called to mind a geography beyond that room, the possibility of travel — of the outside. In the painting’s final form, the outside is represented only by light. The instrument would have evoked music, and even the suggestion of sound would have changed the painting, distracting the viewer from its profound hush. By increasing the size of the cloth in the foreground, Vermeer further protected the woman from intrusion. This technology of looking through a painting and exposing it like a palimpsest gives a rare glimpse into art as a movement toward something that is not always known at the outset. As he worked, Vermeer’s idea about what he was doing was transformed by what he himself saw, and what he saw during the process and came to paint was something simpler and more sacred than what he had imagined to begin with.

But the question remains: Why is this woman so endlessly fascinating, and how does the painting work its magic on the viewer? Many people feel this is clear, but they explain it differently. In his book Éloge du Quotidien (Paris, 1993), Tzvetan Todorov both includes and exempts Vermeer from his subject: daily life in Dutch painting of the period. He argues that by being the highest example of this genre, Vermeer’s work transcends it; that because the everyday is taken to another level, it ceases to be everyday. Notably, he tells his reader to look “again and again” at Woman with a Pearl Necklace. The ordinary act of trying on a necklace in front of a mirror doesn’t look ordinary at all. Vermeer, he says, uses genre themes but doesn’t submit to them. I would take this further and say that while Woman with a Pearl Necklace uses the Vanitas theme as a point of departure, linking it to other paintings of the period showing women at their toilet, Vermeer subverts the theme. This subversion creates ambiguity, and ambiguity creates fascination. Ambiguity in Vermeer, however, is strangely untroubling. This isn’t the uneasy ambiguity of Henry James, for example, where conflicting desires hang in precarious balance or secret motives are buried in appearances. And it isn’t the moral ambiguity that Todorov writes about in paintings of the same period in which moments of ethical indecision are depicted. Vermeer presents the viewer with a painting that resembles other paintings about vanity, and since he lived inside the world of painting and painters, this is clearly intentional; but to assume that the painting must be about vanity because it evokes that tradition is to miss the point. In fact, the longer I looked at the painting, the less its trappings mattered and the more I felt that I was looking at the enigmatic but unalterable fact of another person’s life in a moment of sublime quiet and satisfaction. The mirror suggests Narcissus only to make it clear that he has no place here. The woman’s gaze doesn’t convey desire, but the end of desire: fulfillment.

Edward Snow, in A Study of Vermeer (University of California Press, 1979), reiterates throughout his essay that Vermeer’s great paintings aren’t moral but ontological. When I read his treatment of The Procuress, I was struck by how his reading corresponded to what I’ve always felt about that painting but had found hard to reconcile with its title. Snow argues that despite its vulgar subject, the painting, which has a woman as its radiant focus, conveys the peace of an erotic relationship so natural, so happy, that it defies moral analysis. In short, the woman of The Procuress isn’t bad. All anyone has to do is look at her for a while to know that badness and goodness are not at issue here.

If every painting, particularly those of private life, makes the onlooker a voyeur, most of Vermeer’s women undercut erotic voyeurism with their autonomy — very much in the way that the woman in The Procuress defies the leering onlooker in the painting itself, not by recognizing his leer but simply through the power of her being. It isn’t that Vermeer’s women are without eroticism — their physicality is undeniable — but rather that they resist definition as erotic objects. This fact is all the more marvelous in a painting in which the man has got his hand on the woman’s breast. Even when Vermeer’s women glance back at the viewer or look directly out of the painting, even when his subject is breathtakingly young and beautiful — as is the case in Girl with a Pearl Earring —she appears to be in full command of a separate and whole desire that is hers, not the spectator’s. And although the subject of Woman with a Pearl Necklace invites voyeurism, it deflects it completely. Because she appears to be the object of her own gaze, what she is seeing repeats what the viewer of the painting sees, although from another angle. The mirror then would seem to be the narcissistic end of all this looking: “I love what I see.” This is exactly what happens in the Frans van Mieris painting Young Woman Before a Mirror, where the dark frame of the mirror becomes the imaginary focus (because the woman’s reflection isn’t seen) of sensual desire for the self. But it doesn’t happen in Vermeer’s painting. And it doesn’t happen because we know from the woman’s face that what is being reflected there isn’t self-love and, more important, because the entire far side of the canvas is opened up by the astonishing light that comes through the window.

While I was sitting on the bench in front of the painting, a word popped into my head. I didn’t search for it. It just came. Annunciation. That bench was about six feet away from the painting, and from that distance the light of the pearls disappeared. They are softly illuminated with the most delicate dabs of paint, and I could see them very well when I was standing close to the picture; but from my bench I didn’t see their light anymore, only the woman’s hands raised in that quiet, mysterious gesture and the radiance of the window light, a light that no reproduction can adequately show. When I turned my head, almost as if to shake out the thought, I saw one of the exhibition’s two curators, Arthur Wheelock, standing right beside me and remembered that “the press” had been told that either of them would be happy to answer any questions, and there he was, so I stood up and boldly asked: “Has anyone ever thought of this painting in terms of an Annunciation?” He looked a little funny at first. Then he shook his head and said, “No, but that’s very interesting. I had thought of it as a Eucharistic gesture.” And then, at the same time, we both lifted our hands as if to imitate the gesture of the woman with the pearls, which is itself an echo of the gesture from early Renaissance paintings in which Mary raises her hands toward the angel who comes to tell her that she is pregnant with God’s son. Mr. Wheelock then thanked me a couple of times, which was very nice of him, and the simple fact that he didn’t consider this idea an outrage gave me the confidence I needed to think it through. This thought, or maybe little epiphany, didn’t leave me. I knew there were “Annunciations” buried in my brain that had been triggered by this Vermeer painting. Later, when I was reading through the catalog more carefully, I discovered that among the few things known about Vermeer’s life is that he was summoned to the Hague in 1672 as an “expert in Italian paintings” (Wheelock, Johannes Vermeer, catalog, p. 16).

Читать дальше