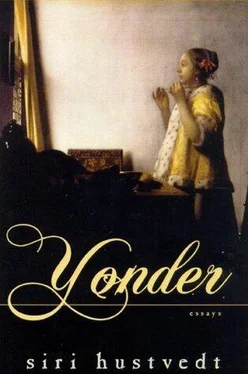

It is impossible to know what art Vermeer saw or what places he visited in Italy — if indeed he went to Italy at all. He converted to Catholicism before his marriage, and the painting of Saint Praxedis shows that, at least once, he painted a specifically Catholic subject, but no one knows whether it was a commissioned painting or not. 1Nevertheless, Catholicism, with its many female saints and the central position of the Madonna, emphasizes women far more than Protestantism, and Vermeer’s art suggests that, at the very least, this feminine side of his new faith must have appealed to him. Wheelock mentions the Eucharist in his catalog essay. Snow writes, “The woman appears not to be so much admiring the pearls in the mirror as selflessly, even reverently, offering them up to the light: it is as if we were present at a marriage.” Two sacraments. Both thoughts are similar ways of explaining an experience of looking at something that feels holy. For Todorov, Vermeer’s ascension is into art. The artist leaps beyond realism into the enchanted space of art itself, a leap that anticipates a much later aesthetic. All these readings are ways of explaining the magic — the secret that announces itself in the painting and doesn’t go away. It may be that Vermeer’s ambiguity allows all these readings, that this is what the painting means, and that, like all great art, it opens a space of possibility larger than what is circumscribed in lesser works.

Nevertheless, I am going to push my intuition further and suggest that the painting is also rife with an allusion to the Annunciation. After I had left Washington and returned to New York, I began mulling over the Annunciation problem and understood that the resemblance I had seen was not only gestural but spatial. On a hunch I turned first to Fra Angelico, who painted several Annunciations, and in his work from the San Marco frescoes in Florence I found an image as motionless as Vermeer’s Woman with a Pearl Necklace. Intended for monastic meditation, the picture is stripped of all ornament and architectural detail. The event takes place in a bare gray cell. As was conventional, the Virgin is on the right as you face the painting, the angel on the left; but in this work there is nothing between them. The space is filled by a soft light that comes from the left, illuminating the back of the angel and the front of the Virgin. But the space is also filled by Mary’s gaze. Her eyes, turned toward Gabriel, are the hypnotic focus of the work; and although her posture doesn’t resemble Vermeer’s woman, it must have been her eyes that my ruminations on Woman with a Pearl Necklace had called forth.

Nevertheless, there was a particular painting I had in mind, although its details had been lost to me, and in it was a Virgin with uplifted hands. I became convinced that I had seen the work in Sienna almost seventeen years ago and knew that I would recognize it if I came across it — and I did. It was a work by Duccio in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Sienna. That it was by Duccio isn’t strange. His Madonnas in the same museum are among my favorite paintings in the world; and when I was there, I spent a long time with them. Because Duccio inhabits that borderland between the icon and the human face of the Renaissance, I have always found his figures achingly beautiful. In Vermeer, I have seen something similar. The threshold is a later one, but in Vermeer the sacred and the human are also joined, and the memory of the icon lives in allegory — the form of allusion in Dutch painting of the time. 2But the Annunciation I remembered by Duccio when I saw it reproduced was The Annunciation of the Death of the Virgin. So, surely, if Vermeer knew his Italian art, he would be making no specific reference to this work. After digging about, however, I discovered that the Virgin is shown with uplifted hands in a number of Annunciation paintings, that this posture does belong to the iconography of gesture in both Italian and Flemish paintings of the period. Two examples to turn to are one by Giusto de’ Menabuoi (1367) and one by Dieric Bouts, painted a hundred years later. 3

At the recommendation of a friend, I turned to a book by Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (Oxford University Press, 1972). Among other things, the author discusses physical gesture in painting of the period, noting that “the painter was a professional visualizer of holy stories” for a public that through spiritual exercises was well versed in a similar task — seeing in their minds events from the lives of Christ and Mary. He cites a sermon by Fra Roberto Caracciolo da Lecce on the Annunciation as an example of popular preaching on the Immaculate Conception. In the sermon, Fra Roberto first discusses the “angelic mission.” One of its categories is time: the Annunciation took place on Friday, March 25, either in the morning or midday during the spring, when the earth was blooming after winter, an idea only broadly relevant to the Vermeer painting, in that it is obviously midday light that pours through the window. The “angelic colloquy,” also discussed in the sermon, is a dissection into five stages of the biblical passage in Luke. Baxandall points to the colloquy as a guide to understanding the Virgin’s gestures in paintings that depict the Annunciation at its various moments, from the first stage, Conturbatio (Disquiet) to the last, Meritatio (Merit). What Baxandall’s discussion clarified for me was that although pictures of the Virgin were heavily coded, they weren’t dictated by the church. Within that code there was significant range for the painter’s own vision of how the Virgin’s body would express Disquiet, for example. The painted images are a combination of convention, spiritual teaching, and imagination.

But it was the second stage of the colloquy that grabbed my attention: Cogitatio (Reflection). The Virgin receives the salutation of the angel and reflects on it. Knowing this places the mirror in Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a whole new context. Isn’t that mirror, contiguous to the radiant window, a buried allusion to the Annunciation, and very likely to this second stage — Reflection?

Because I wanted to see more Annunciation paintings, I took a tour of the Metropolitan Museum, in New York, looking for them at random. I turned a corner and ran straight into the Petrus Christus painting of the event (a work that has also been attributed to Jan van Eyck) and was stopped in my tracks. I had seen it before but had never registered it deeply in my private catalog of remembered paintings. Although the Virgin’s gesture is not like that of the woman with the pearls (she has one hand near her neck, clasping the folds of her cloak, while the other hand holds a book), I had discovered a Virgin whose posture is as erect and whose gaze is as clear and unflinching as Vermeer’s woman. Between the Virgin and Gabriel is the Holy Spirit, depicted as a bird that gives off painted rays of light. The Virgin stands at the threshold of a door that divides the painting between inside and outside. The angel stands beyond the domestic interior. As I looked at this painting, it became even more apparent that my insight about the Annunciation — half unconscious as it was — rose out of not one, but many diffuse references in Vermeer’s painting — that not only the woman’s hands suggest the Annunciation, but so do the light from the window, her gaze, her posture, and that it is this accumulation of detail that produces the painting’s feeling of quiet sanctity.

There is one further thing in Woman with a Pearl Necklace that confounded me from the instant I noticed it in the gallery. Above the window frame near the folds of the curtain is a small, egg-shaped detail. The truth is that when I first looked at it, I thought: What’s that egg doing there? That “egg” is probably part of the window’s architecture, and yet it appears to be almost distinct from it. In the museum, I went right up to it, but the closer I came to it, the harder it was to decipher. It appears as light and shadow itself or perhaps paint as light and shadow itself. But what’s it doing there? We know that Vermeer changed the world he painted as he saw fit. Although he was interested in creating a feeling of realism, he changed objects, colors, shadows, even perspective at will to make what he wanted to make. Surely he wanted that oval “thing” on his window or he would have eliminated it. I started looking for that shape on other opened or shut windows in Vermeer’s work, but couldn’t find it. This round architectural detail contrasts with the linearity of the rest of the window. It echoes the shine of the woman’s earring, the subtle gleam of her pearls, the roundness of the dark covered jar, the bowl, and the roundness of her own form — the flesh of her face and arms, all the while looking decidedly egglike. No wonder scholars have gone crazy “interpreting” Vermeer. There is allegorical allusion in his paintings, signs that can be read but that are also hidden inside ordinary rooms and in the faces of “real” people, and necessarily so, because these paintings are neither one thing nor the other. They are both.

Читать дальше