Paul often says that it’s a strange business, this sitting alone in a room making up people and places, and that in the long run, nobody does it unless he has to. Years ago, he translated a French writer, Joseph Joubert, whose brief but startling journal entries have become part of our ongoing dialogue about art. Joubert wrote: “Those for whom the world is not enough: poets, philosophers and all lovers of books.” When I read Death on the Installment Plan in my early thirties, the book in which I imagined the hero in my grandparents’ house, I loved it so much I was sorry to finish it. I closed the book and shocked myself by thinking, “This is better than life.” I didn’t mean or want to think this, but I’m afraid I did. Certainly this feeling about a book is the one that makes people want to write. I don’t know why I feel more alive when I write, but I do. Maybe I imagine that if I scratch hard enough into the paper, I will last. Maybe the world isn’t enough, or maybe the distinction between the world and fiction is not so clear. Fiction is made from the stuff of the world, after all, which includes dreams and wishes and fantasies and memory. And it is never really made alone, but from the material between and among us: language. When Mikhail Bakhtin argues that the novel is dialogical — multivoiced, conflicted, in constant dialogue within itself — he is identifying all those jabbering voices every fiction writer hears in his or her head. Writing novels is a solitary act that is also plural, and its many voices are forever placing us somewhere — here or there or yonder. At the same time, writing collapses these spatial categories. Like a heartbeat or a breath, it marks the time of a living consciousness on the page, a consciousness that is present and here, but also absent. The page can resurrect what’s lost and what’s dead, what’s not there anymore and what was never there. Fiction is like the ghost twin of memory that moves through the myriad cities, landscapes, houses, and rooms of the mind.

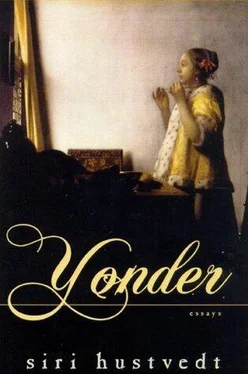

Every painting is always two paintings: the one you see and the one you remember, which is also to say that every painting worth talking about reveals itself over time and takes on its own story inside the viewer. With Vermeer’s work, that story probably lasts as long as the person who sees it. This is my own unfinished story of looking at one of his paintings. Before I walked through the doors of the National Gallery of Art in Washington to look at its historic gathering of twenty-one of Vermeer’s works, I hadn’t decided which painting I would write about. My job was to discuss only one, and while I was paging through the catalog and listening to the museum officials and curators talk about the show, I turned to Woman with a Pearl Necklace. I had never seen the original, although I had admired it in reproduction many times, but suddenly, for reasons I didn’t fully understand, this painting of a woman holding up a necklace in the light of a window jumped out at me. Although I didn’t have the slightest notion of what I would say about it, the choice had been made, and I walked up the stairs already in its grip.

I spent four hours in the gallery, two of which were spent solely in front of Woman with a Pearl Necklace. I looked at it from close up. I looked at it from several feet away. I looked at it from either side. I counted drops of light and scribbled down the numbers. I recorded the painting’s elements, working to decipher the murky folds of the large cloth in the foreground. I noted the woman’s hands, her orange ribbon, her earring, the yellow of her ermine-trimmed jacket, the mirror frame, the light. I never touched the painting, of course, but once I was reprimanded by a guard. Perhaps my nose came too close to the paint or perhaps my obsessive focus on one painting struck him as slightly deranged. He waved me off, and I made an attempt to look less awed and more professional. There was a bench in that room, and after my dance of distances, I sat down on it and looked at the canvas for a long time. The more I looked at it, the more it overwhelmed me with a feeling of fullness and mystery. I knew what I was looking at, and yet I didn’t know. I had to ask myself what I was seeing and why it had become an experience so powerful, I felt I couldn’t have lasted another hour without crying. It seemed to me that both because of and despite its particularity, Woman with a Pearl Necklace was something other than what it appeared to be. This is an odd statement to make about a painting, which is literally “appearance,” and yet I couldn’t help feeling that the mystery of the painting was pulling me beyond that room and its solitary woman.

Every viewing of a painting is private, an experience between the spectator and the image, and yet I would wager that the feelings evoked by this painting are remarkably similar, particularly for those who aren’t burdened with historical interpretations and the problem of puzzling out Vermeer’s intentions. Even the most cursory glance at Vermeer scholarship suggests that there is much disagreement. But I am not an art historian, and those disputes won’t come into the story until later. My intention that day was simply to look at this painting, to study it with fresh eyes, and to let the painting and only the painting direct my thoughts. In that gallery in the museum, I looked at the profile of a young woman who is apparently looking at herself in a small mirror. The mirror is only slightly larger than her own face and is represented by its frame only. In fact, the viewer assumes there is glass in the frame only because of the way the woman stands and gazes toward it. But what we imagine she is seeing — her own face — is not part of the painting. The window is so close to the mirror, and its light so clear and dominant on the canvas, that whether she is transfixed by the mirror or by the window isn’t entirely clear. My first impression of the painting was that she was looking at the window, although the longer I looked at it, the less sure I became. The woman’s gaze is not dreamy but active, the focus of her eyes direct; and although her feet cannot be seen under the shadowed folds of her skirt, they seem to be firmly planted on the floor. Her soft lips aren’t smiling, but there is the barest upward tilt at the visible corner of her mouth. And yet there is no feeling that she is about to smile or that her expression will change anytime soon. Her hands aren’t moving either. She isn’t tying the necklace. She has stopped in mid-gesture and is standing motionless. One look at The Lacemaker (also in the show), a painting in which a girl’s fingers are caught in action, confirmed for me that the hands of the woman with the pearls are frozen. In fact, the painting is stillness itself — a woman alone and motionless in a room. I am looking in at her solitude, and she cannot see me.

In a number of Vermeer’s paintings, the spectator is seen. Girl with a Red Hat and Girl with a Pearl Earring (both in the Washington show) are paintings in which the spectator and the subject exchange looks, and although neither of these paintings is large, each depicts a partial rather than a whole body. We see only the upper body of the girl with the hat, and only the head and shoulder of the girl with the earring. This focus on faces creates intimate access into the painting for the viewer — two faces meet for what becomes an eternal moment. On the other hand, the woman with the necklace doesn’t acknowledge the presence of any onlookers, and the viewer is barred from entrance to the room on two counts. First, the small size of the painting, which holds her entire body, places her in another perspective from that of the onlooker: my dimensions are radically different from hers. And second, the entire foreground of the painting — a large chair and a table draped with dark cloth and topped with a gleaming black covered jar — would have to be shoved aside before anyone from the viewer’s position could even imagine stepping into the luminous space she occupies.

Читать дальше