"In the thirty or forty years I've been sitting here, the city centre's changed every time someone has taken over the local government," she said, pointing to the buildings towering over her poky lane. "Those houses to your left date from the 1950s. Hardly anything was built during the Cultural Revolution, but the ones opposite are from the 1980s, while the buildings to the right went up within the last two years. Now I hear the new mayor wants to rip them down and start again! As soon as they have a bit of cash in their pockets, officials always want to show off, changing everything too quickly for anyone to catch up. But no one's ever thought of fixing this crumbling old lane of ours, even though hundreds of people live here. I'll retire when they finally do something about that," she laughed.

We waved goodbye to Yao Popo, but every straight nose I have since seen has made me think of her – an old woman whose yearning for beauty had not been ground out of her by poverty.

2 Two Generations of the Lin Family: the Curse of a Legend

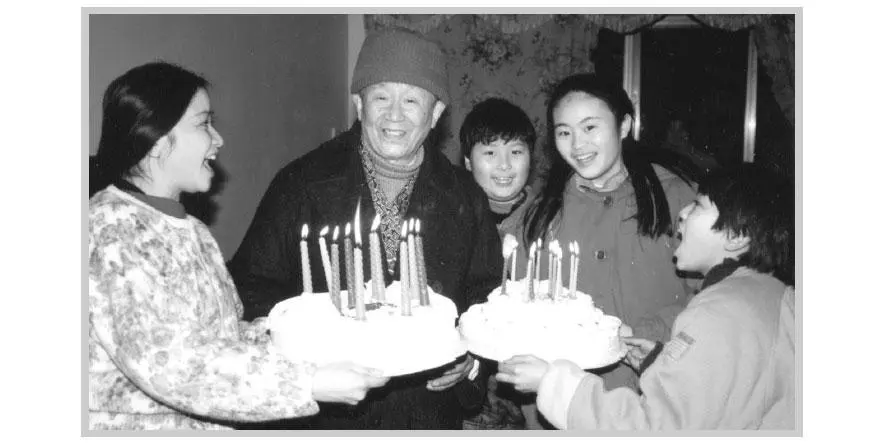

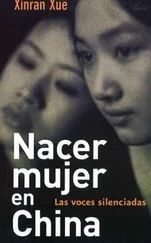

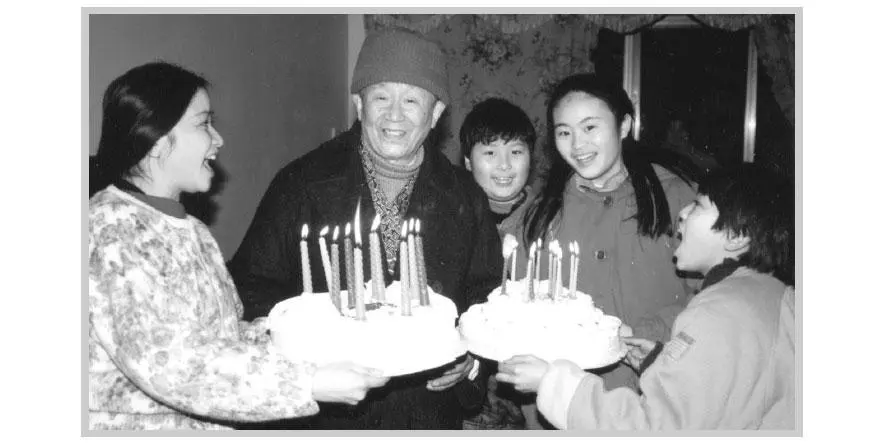

From left , the "Double-Gun Woman", Lin Zhuxi (Mr Lin's father), her son-in-law Lin Xiangbei, and his wife.

Mr Lin with his daughter and grandchildren.

LIN XIANGBEI, aged eighty-nine, son and son-in-law of revolutionary martyrs, interviewed in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in south-western China. Lin's father called him "comrade" when he was ten, and Lin joined the Communist Party before he was twenty. But he was branded a counter-revolutionary because he married the daughter of Chen Lianshi, the legendary "Double- Gun Woman", a Chinese revolutionary, and because his father had been Chen Lianshi's lover. He spent over twenty years as a political prisoner and lost family members on both sides during the struggle between the Communist Party and the National Party from the 1930s to the 1970s. Six of his seven children survived more or less as orphans.

In China, the "Double-Gun Woman" is a national heroine: a legendary female revolutionary, ruthlessly dispatching enemies and traitors with a gun in each hand, dry-eyed even at the deaths of her husband and children – as fast as a bandit, as tough as a peasant.

In the Archives of the Imperial Academy stored in Beijing Library (which, by some miracle, survived the Cultural Revolution), we can trace the family history of the Double-Gun Woman, Chen Lianshi, back through several generations. Her earliest traceable ancestor on her mother's side is an imperial academician from Sichuan called Kang Yiming, who served during the reign of the Qing emperor Jiaqing (1796-1820). Her father's forebears were equally illustrious, many of them scholar-officials or high-ranking military men.

After the foundation of the Republic in 1912, several members of the family left Sichuan to study elsewhere, some heading to Japan, some joining Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary Tongmeng Society. Having been, in the last years of the Qing, a high-ranking official renowned for his justness and benevolence, and for his work in helping the poor and needy, her father was selected as member of parliament for the area.

Sources that emerged during the 1980s state that, as a girl, "the Double-Gun Woman demonstrated exceptional intelligence, covering in two and a half years the curriculum that took most students seven. After enrolling at the local women's Normal College, she then passed the entrance examination to one of the country's top universities in Nanjing, where she hoped to help her country by studying to become a teacher. She excelled also at painting." The Double-Gun Woman was clearly neither a poor peasant, nor an illiterate bandit.

In Communist China, the designation of national heroes has been a fiercely controlled business. Under Mao, in particular, only members of the proletariat – workers or peasants – were officially permitted to be heroic. More or less since Chinese history began, the country's great patriotic heroes have been mostly male: unflinching individuals permitted to shed tears in only two cataclysmic sets of circumstances: at the death of their mother, or the loss of the motherland. With the rise to power of the Communists – and of the idea that "women hold up half the sky" – women, too, were allowed to become national heroes, but only in the superhuman, patriotic male mould. When I was very small, I saw Red Crag , a classic revolutionary film of the 1960s featuring the Double-Gun Woman. In a 1995 book about her published in China, Chen Lianshi wasn't allowed to behave like normal women – weeping at the execution of her husband, or at the death of her daughter. She had to be invulnerable: a Party killing machine devoted to robbing the rich to help the poor.

A few years ago, while researching the possibility of publishing a book about the Double-Gun Woman outside China, I was lucky enough to meet her son-in-law, Lin, her grandson and her five granddaughters. After I had heard them talk about their mother and grandmother, she began to take shape in my mind. In particular, three things furthered my understanding of this national heroine and of the historical period she lived through.

The first was a 1926 painting by her, A Fish Rises to Jiang Taigong's Bait. At the time, her husband had been seriously wounded in an armed uprising against a local warlord, in which a great number of their comrades-in-arms had been lost and many others had gone over to the enemy. In these bloodily uncertain circumstances, the unit to which the Double-Gun Woman belonged found itself under constant threat of annihilation. Studying the delicate strokes of the fish scales and the ripples in the water, together with the relaxed lines of the fisherman, it seems incredible that the painting was completed in such dire circumstances. It is equally hard to imagine that the hand capable of such refined brushwork could, hours, or even minutes later, take up a gun and open fire with ruthless impunity. How could a single individual be made up of two such contradictory impulses? The turmoil of twentieth-century China has forced its people – its artists included – to coexist for long periods of time alongside the near constant threat of violence. While war has not succeeded in annihilating modern Chinese culture, it has left an indelible imprint on its development.

Second, I learned that the Double-Gun Woman had had two lovers. The first had been her husband, killed by the Nationalists. What had attracted Chen Lianshi – so exceptional in both looks and talent, a woman who could have had any man she chose – to an obscure young man from the countryside? It was not only his looks and abilities, but also his courage: the courage to stand in the vanguard of his era, to wake – in a people numbed by the suffering of war – a new sense of national pride and dignity. The second was Lin's father, an unconventional idealist who stood by her for the rest of her life though she would never marry him. As a surrogate for the married life they could never enjoy themselves, they eventually betrothed their two children – Lin, and Chen's daughter, Jun. Chen's husband was her inspiration, a soulmate to whom she would remain loyal till her death by refusing ever to remarry, while Lin's father provided her emotional ballast, willing to efface himself almost completely to give her the unconditional love and support she needed.

These two different presences in her life – the great love to whom she devoted herself, and the emotional prop from whom she drew the devotion she herself required – comfortably complemented each other. A great many people feel the need for similar kinds of close, complementary relationships in their lives. But for thousands of years, right up until the 1980s, Chinese women who required ballast outside their marriages were condemned as faithless "bad women", and were punished, even murdered by their fathers and husbands for forming such attachments. Like so many chaste widows of the Chinese past, the Double-Gun Woman, widowed at thirty-five, put up with decades of lonely nights after her husband's death, in order to protect her reputation. I don't know how she stood it. At no point in Chinese history was it ever suggested that remaining virtuously loyal to a dead husband's memory was a form of tyranny, or self-harm. Even the Double-Gun Woman – in all other respects, a liberated, educated modern Chinese woman – found herself unable to shake off the shackles of tradition, demonstrating the slow pace at which civilisation changes and progresses.

Читать дальше