© 2008

To the Mothers of China

and my mother, Xujun

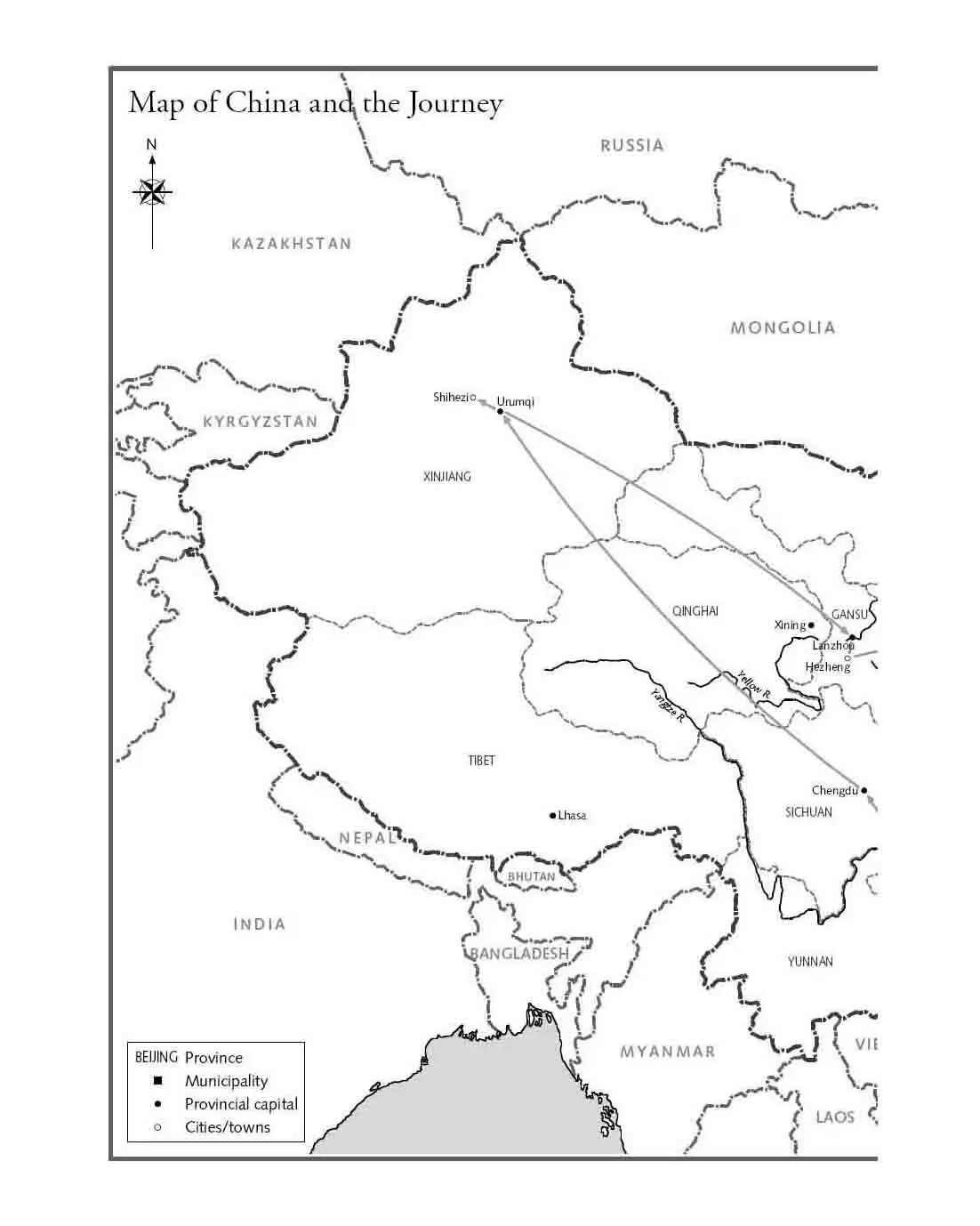

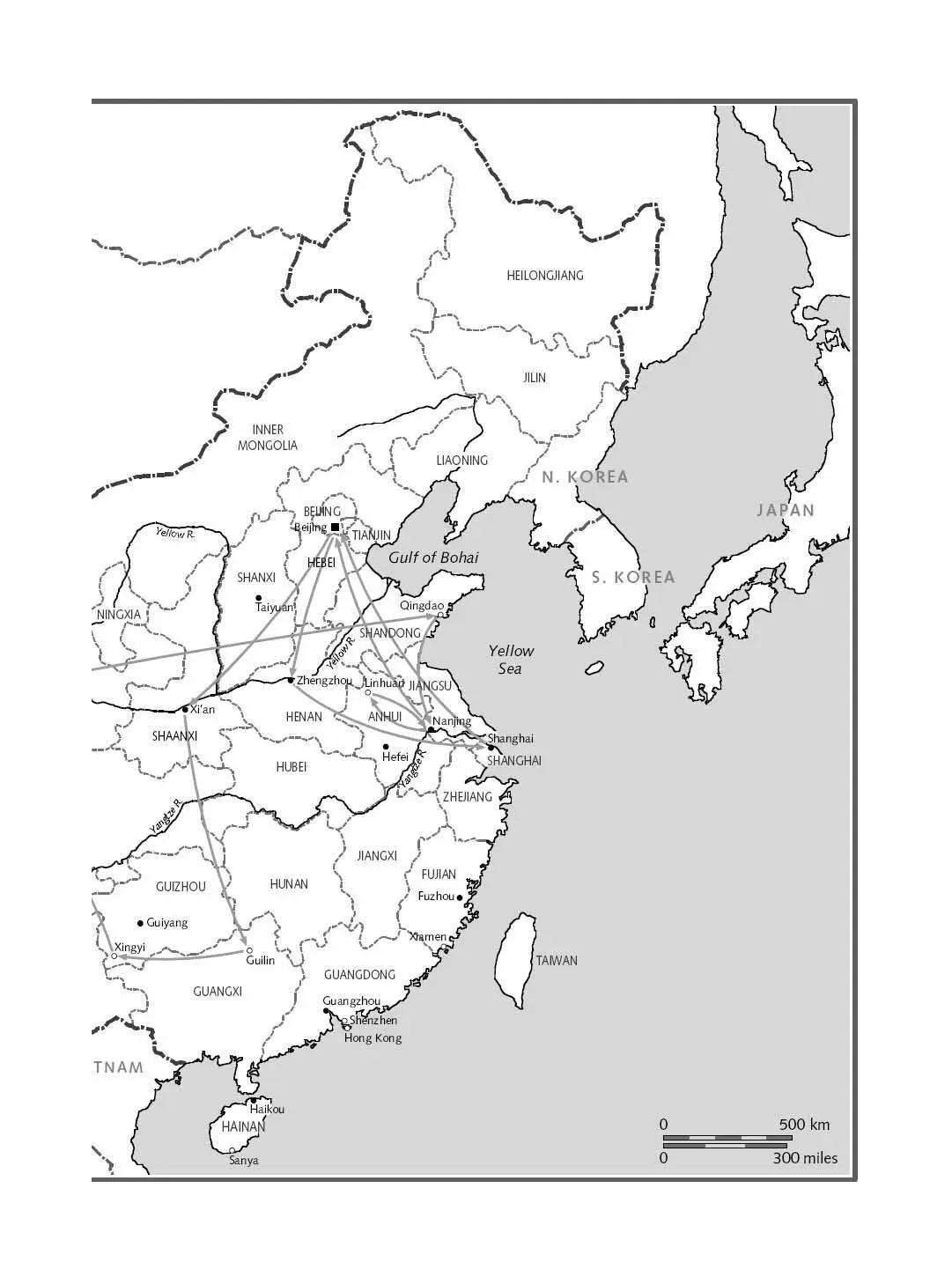

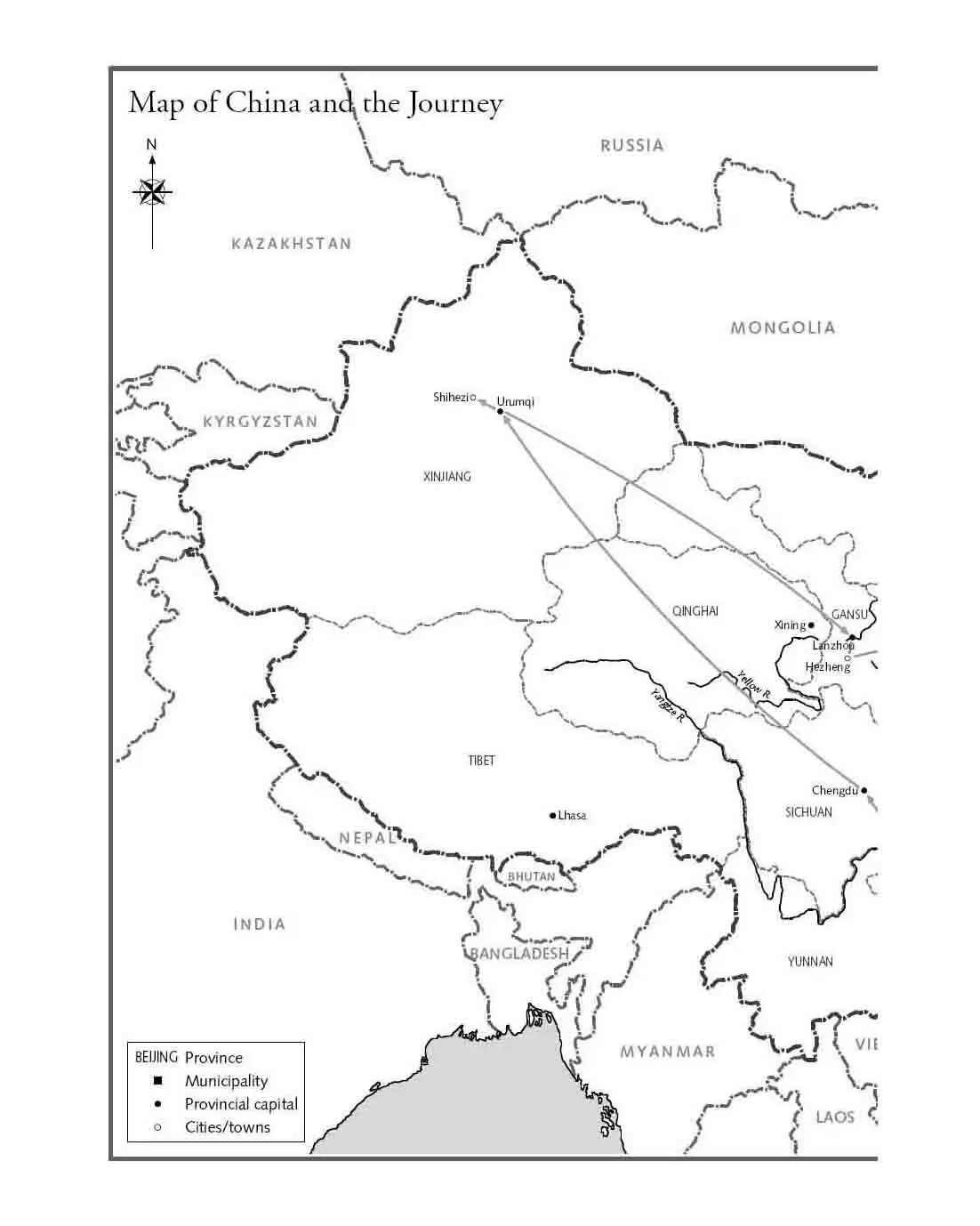

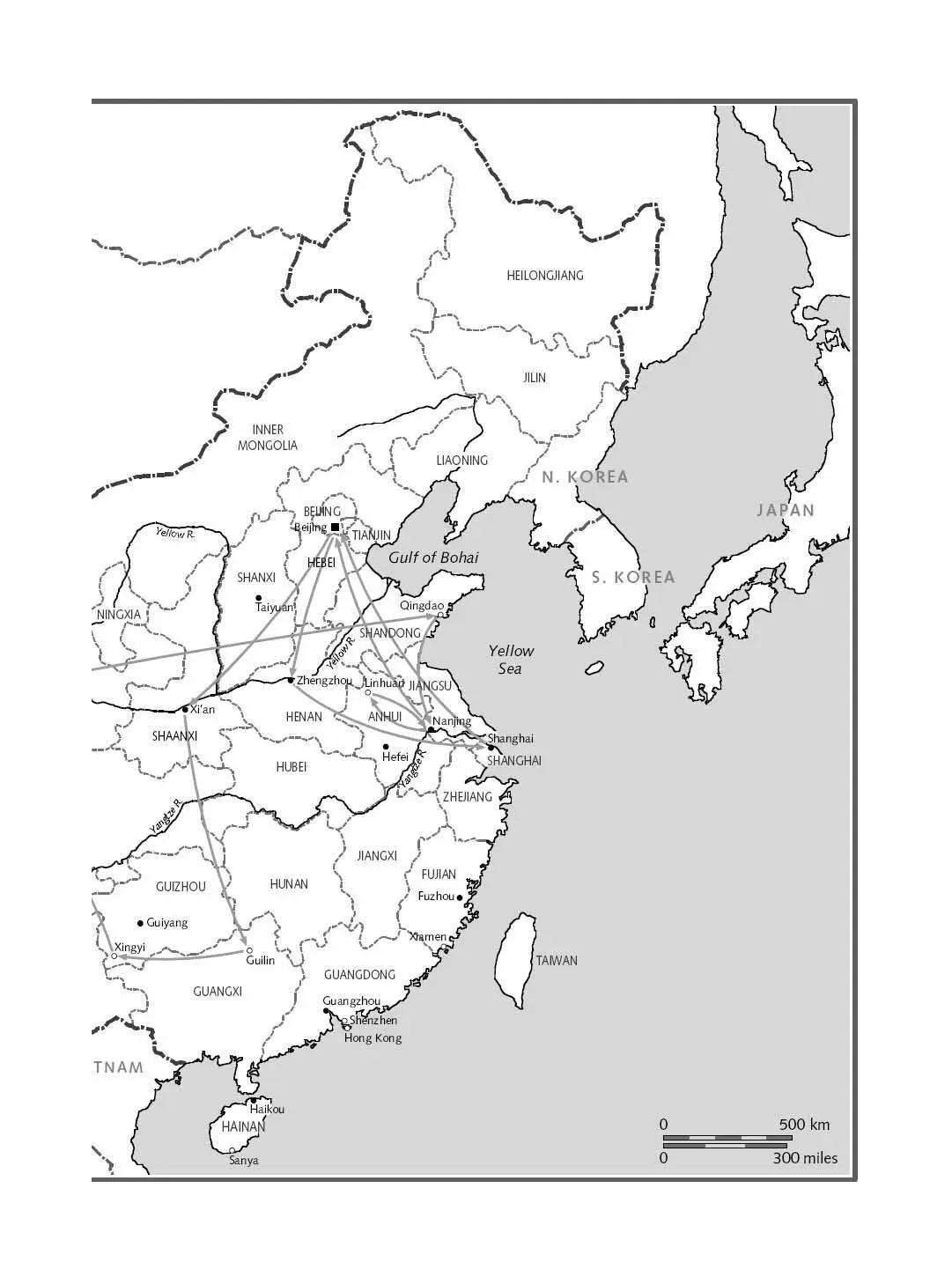

Map of China and the Journey

***

Illustrations

Chapter 1: A herb shop, Xingyi, 2006.

Chapter 2: "Double-Gun Woman" with her family.

Her son-in-law, Lin Xiangbei, with daughter and grandchildren.

Chapter 3: Workers of 148 Corps, 1950s, Shihezi.

With survivors of 148 Corps, Shihezi, 2006. (Photo Kate Shortt)

Chapter 4: Oil pioneers, north-west China, 1950; and in Hezheng, 2006.

Chapter 5: Acrobats practising, 1950s, and on tour, South America, 1990s.

Chapter 6: The news singer reciting, 2006.

Traditional tea house, 2006. (Photo Kate Shortt)

Chapter 7: Lantern workshop, Nanjing, 1950s, and a lantern-maker, 2006.

Chapter 8: A survivor of the Long March, 1947 and 1987.

Chapter 9: General Phoebe as a child, Chicago, 1933, and in Beijing, 2006.

Chapter 10: A policeman with his family, Zhengzhou, 1960s and 2001.

Chapter 11: A shoe-mender woman, Zhengzhou, 2006. (Photos Kate Shortt)

(Unless otherwise indicated above in brackets, photos are from the author's collection and supplied by kind permission of interviewees.)

Glossary and Abbreviations

CCP: Chinese Communist Party, the ruling party of the PRC, founded 1921.

GMD: Guomindang (also Kuomintang/KMT), the Nationalist Party, founded 1912; for many years the most powerful party in China, defeated by Mao Zedong's PLA forces in 1949, when the GMD retreated to Taiwan where it survived as the dominant political party until 2000.

PLA: People's Liberation Army, founded 1927 as the military arm of the CCP to put down GMD rebellion in the Nanchang Uprising of August 1927; originally known as the Chinese Red Army, it was established as the PLA at the end of the Sino-Japanese war in 1945, when China's civil war continued and the PLA finally defeated the GMD in 1949. Comprising all China's military forces, it is now the world's largest standing army.

PRC: People's Republic of China, established 1949, at the end of the Chinese civil war.

Han Chinese: the largest single ethnic group native in China, making up about 92% of the population of the PRC.

Hui Chinese: a mainly Moslem Chinese ethnic group, one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognised by the PRC.

xiucai: one of the degrees of the competitive Imperial examinations for entry to provincial government bureaucracy which survived into the twentieth century.

Three Antis (1951) and the Five-Antis (1952): Mao Zedong's campaigns aimed at rooting out corruption and enemies of the state, particularly in bureaucracy and business; targeting his political opposition and capitalists, these movements consolidated his power base

Three Red Banners: the 3 principles held up in the 1950s for the building of socialism – the General (Party) Line, the Great Leap Forward and the People's Communes.

Great Leap Forward: Mao Zedong's Second Five-Year Plan, 1958-60, intended to transform China rapidly into a modern industrial society, which resulted in famine and ended in economic and humanitarian disaster, during which millions of Chinese starved to death.

Reform through Labour (Laogai): a slogan of the criminal justice system of convict labour instigated by Mao Zedong in the 1950s, modelled on the Soviet Gulags.

Four Clean-Ups: a movement, also called The Socialist Education Movement, launched by Mao Zedong in 1963 to cleanse reactionary elements from politics, economy, bureaucracy, ideology.

Reform and Opening: the opening up of China and relations with the West under Deng Xiaoping.

Currency:

1 yuan (CNY) = 10 jiao = 100 fen

1 UK pound = approx. 14 yuan (May 2008)

1 US dollar = approx. 7 yuan (May 2008)

1 yuan = approx. 7 pence/14 cents (May 2008)

Oil:

Oil in China has historically been measured in tonnes rather than the more familiar barrels.

1 tonne oil = approx. 7-9 barrels, depending on the type of oil.

This book is a testament to the dignity of modern Chinese lives.

It has been not only a personal journey for me through the experiences of my parents' generation, but also – for my interviewees – a process of self-discovery, of revisiting and refining their memories of the past. While I have wondered what questions to ask, they have needed to think about what answers to give; about how to describe a twentieth century that, in many respects, has been full of suffering and trauma. For Chinese people, it is not easy to speak openly and publicly about what we truly think and feel. And yet this is exactly what I have wanted to record: the emotional responses to the dramatic changes of the last century. I wanted my interviewees to bear witness to Chinese history. Many Chinese would think this a foolish, even a crazy thing to undertake – almost no one in China today believes you can get their men and women to tell the truth. But this madness has taken hold of me, and will not let me go: I cannot believe that Chinese people always take the truth of their lives with them to the grave.

Why do the Chinese find it so hard to speak frankly about themselves?

"The concept of guilt by association," Professor Gao Mingxuan, an authority on the Chinese penal code, has remarked, "was always very important in ancient Chinese law. As early as the second millennium BC, a criminal's family was punished as harshly as the criminal himself. Over the next thousand years, this principle steadily tightened its grip on the judicial system. In his canonical history of China, written around 100 BC, Sima Qian recorded that 'after Shang Yang ordered changes in the law [ c .350 BC], the people were grouped in units of five and ten households, carrying out mutual surveillance, and mutually responsible for each other's conduct before the law'. If a member of one family committed a crime, the other families in that unit were judged to be guilty by association. By the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC), the principle was applied not only within communities, but also within the army and government. In the case of minor offences, the criminal's family would be exterminated to between three and five degrees of association; with serious offences, to nine or ten. Although the virtues of this penal principle were debated at various points in the imperial past, it remained a mainstay of the Chinese judicial code until the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911)."

China does not have a monopoly on the idea of collective responsibility in criminal law. In 1670, for example, Louis XIV installed just such a principle in France's penal code: entire families – including children and the mentally ill – were to be killed for an individual's crime. Sometimes, whole villages would be condemned, with even the dead posthumously disgraced.

In China, the deep historical roots of the principle of guilt by association gave rise to powerful traditions of clan loyalty, instilling in the Chinese a strong inhibition towards the idea of speaking out openly – out of a fear of implicating others.

None of the cataclysmic changes brought by China's twentieth century – the fall of the Qing dynasty, the chaos of the warlord era, the Sino-Japanese War, the civil war, the Communist revolution – has succeeded in dislodging this strong clan consciousness. The Chinese people still seem to lack the confidence to speak out on what they really think – even as the post-Mao reforms have slowly opened doors between China and the outside world, between China's past and future, and between the individual and government.

Читать дальше