Pressing my advantage, I asked if I could have permission to remain in the flat for the next six months. This I got; and it was renewed afterwards every six months without question. I wrote a standard letter stating that I was still in receipt of this entirely notional sixty-five pounds a month, and by return post came the permission. This was one of the few occasions when I had to bluff and trust to luck. It worked, and-1 had overcome the two main hurdles a spy has to surmount. I had a fixed and legal base, and my means of communication were secured. These two obstacles trip up ninety per cent of the spies who end their lives on the scaffold or in the cells. The victims are caught either through their means of communication- by radio monitoring or censorship - or because they have been unable to legalise themselves in the country where they are operating. It is practically impossible to be an efficient spy and be, at the same time, perpetually on the run. It was not too bad for me, as the worst that I had to expect from the Swiss was a period of imprisonment; while, if I failed to get established, I could always go quietly to ground with one of Rado's friends who had little to fear- the penalty for sheltering a spy in a neutral country being comparatively slight. Admittedly I was caught in the end, and caught through my means of communication like most of the rest. But thanks to the thrift of the Swiss and the mellowing effect of scotch whiskey I had almost three years' run for my money.

With myself legalised and the aerial installed I had merely to get the set working and contact Moscow. This was not too easy. I had already spent six weeks in dealing with the police and getting my dilatory mechanic on to the job and now I was anxious to get the set going without delay. But when I resurrected the bits of the transmitter from their hiding places and set the whole thing up, the crystal refused to oscillate. After a great deal of trial and error (after all I was not a trained radio mechanic and Hamel and his professional advice were not available to me in Lausanne) I managed to get the set to work by shortening the lead-in and installing the apparatus in the kitchen. This was not in the least convenient, but it was safer, as it ensured me against casual interruption, for it was unlikely that any unwanted guest who arrived during my transmitting times would penetrate to the kitchen. At least I could do my best to stop him and the arrangement saved my having to think up an easy and quick way of hiding the transmitter, which would have been necessary had I installed it, as I had at first wished, in my living room.

With the set now working, I had only to contact Moscow, and in my innocence I imagined this would be an easy task. Night after night, with my receiver tuned to the wave length given me in my schedule, I called at the arranged times. My tappings went out onto the unreceptive ether. Moscow could not or would not hear. Several times I almost decided to give up for the moment and go to Geneva and ask Rado to put a message over his set-which I knew now to be working in Hamel's flat-asking Moscow to listen carefully and let Rado know if I was getting through or whether the set was still faulty. I banished this temptation, as the one thing we were anxious to do was to keep the two sets as unconnected as possible. I settled down again with renewed patience and continued calling. It was all the more irritating because the whole time I could hear Moscow calling me: "NDA NDA NDA," but they continued merely to call and I could get no indication that they could hear me, merely the perpetual reiteration of the call sign, as maddening to taut nerves as a dripping tap.

Persistence, however, won its ultimate reward. On March 12 for the thousandth time I tapped out the call sign "FRX FRX FRX." Then through the hum and crackle of static and over the background noise of other signals I heard "NDA NDA OK QRK 5." (QRK 5 indicated in the "Q code" that my signals were being heard very strongly.) Contact had been established.

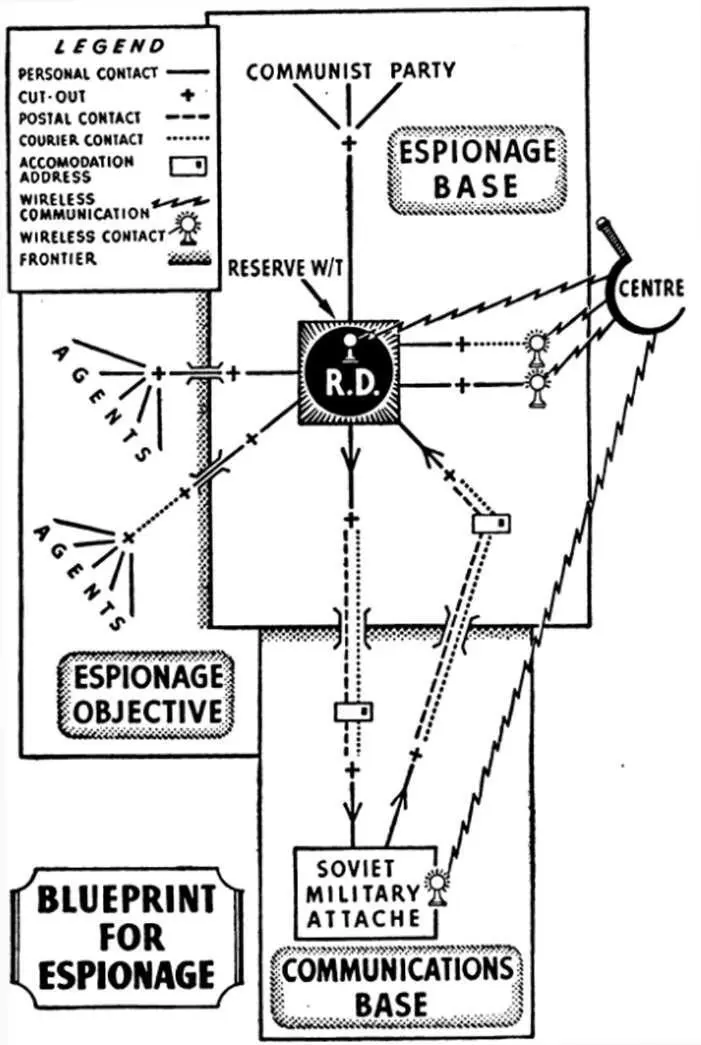

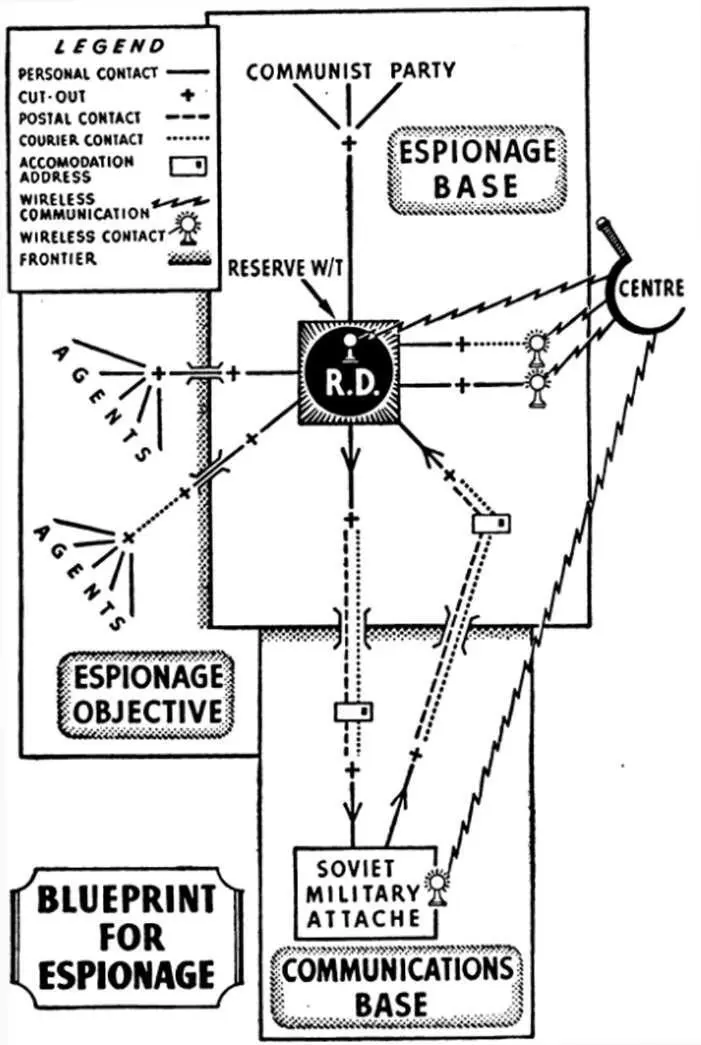

There now follows a description of the layout of a Red Army espionage network in theory. It is the blueprint which all networks abroad attempt to follow. I can of course speak only for the Red Army system, as that is the only one I know. I should imagine that the Red Fleet or N.K.V.D. (now M.V.D.) network would be organised on approximately the same lines. It is, in fact, an eminently practicable, simple, and effective system, giving the maximum degree of efficiency with the minimum danger of compromise.

The head of the network is, of course, the resident director. Except in exceptional circumstances, he does not reside in the country against which his network is operating but lives and directs the organisation from a convenient neighbouring country against whose interests he is forbidden to work. It naturally happens on occasions that a resident director obtains information concerning his country of residence. In such cases, in normal times, he would hand the development of the source over to another resident director whose network was directed against the first director's country of residence. For example if the resident director in Switzerland of the network against Germany discovered a source who was capable of producing information from the Swiss General Staff, he would hand the source over to the resident director of the network working against Switzerland, who would probably be resident in France, and leave the latter to work out ways and means of getting the information to Moscow. The reason for this is obvious. The local police or counterespionage authorities are likely to take a much greater interest in the activities of anyone they suspect of working against them than they are in an individual who, while resident in their country, is working against a foreign power. Also the chances of compromise through treachery or double agents are much greater if the resident director is living, as it were, on top of his sources. It is, in fact, an extension of the old maxim about dirtying one's own doorstep.

The resident director is also, usually, not a native of his country of residence. He is usually not a Russian either, and in fact few Soviet nationals are used in Russian espionage networks. The Centre (i.e., Moscow) finds that the difference between the way of life in Russia and other countries is so great that it is difficult for Soviet citizens to adjust themselves. Also a Soviet citizen is a much more likely target for suspicion than a person of another nationality. It used to be said that "even- Japanese is a spy." This applies equally well to Russians, as it is impossible for a Russian to get abroad until he has been checked and double-checked by the N.K.V.D. and is known to be one hundred per cent politically reliable. This is equally well known to all foreign counterespionage authorities, who as normal routine take a considerable interest in the activities of any Russian national in their midst.

The resident director is also usually forbidden to search for and develop sources of information. It is not for him to recruit agents or to conduct operations. His tasks are to control the communications system, cope with finance, sort out, evaluate, and edit the information that comes in to him, encipher it for onward transmission to the Centre, and generally to supervise and conduct the work of the whole organisation; seeing that the right lines are being developed and exploited at the right time, but keeping in the background and restricting knowledge of his identity to the minimum number of people. He is usually unknown to his agents, couriers, and radiotelegraphists, maintaining contact with them only through his liaison agents or "cut-outs," who are the only people aware of his identity.

Читать дальше