We did, however, and laughed appreciatively. Donovan then asked me whether the Russians had ever discussed the Red Chinese with me. I replied that they had never brought up the subject in conversation; in reading the Daily Worker , however, and on listening to radio news as translated by my cellmate, I had heard them occasionally bemoan the unfairness of excluding China from the UN. However, I added, both my cellmate and I agreed that that was probably the last thing in the world the Russians wanted.

In the same spirit of charity extended to me by Donovan, I will only say that his recollections of our conversation are hazy.

Later there was a letter. Negotiating to sell his book to Hollywood, he was willing to offer me twenty-five hundred dollars for use of my name and story. Permission wasn’t necessary, he said, but he had personally arranged this for me. As an extra added incentive, he might also be able to arrange for me to play myself in the movie, should I so desire.

I was tempted to reply that since the mercenary Powers had passed up sixty times that amount by deciding not to write his book, he was placing a rather high price on my vanity.

But I didn’t.

I was, and remain, grateful to him for the part he played in my release. But I also want to keep the record straight.

My first meeting with former CIA Director Allen Dulles seemed preordained, one of those meetings decreed by fate. The second meeting, while not a surprise, did catch me off guard.

In March, 1964, the Lockheed Management Club hosted a dinner at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Chief speaker was Dulles. Sue and I were there, to hear our former boss. We entered the room just behind Mr. and Mrs. Johnson, who were escorting Mr. and Mrs. Dulles. Spotting me, Mrs. Johnson said, “Oh, Mr. Dulles, I believe you know Francis Gary Powers.”

It was not a name he was likely to forget.

His greeting was most cordial, as was mine. I had never considered Dulles responsible for the role into which I had been placed; that decision, I believe, had occurred during the reign of his successor.

After acknowledging his introduction, Dulles departed from his prepared speech: “I want to say, too, as I start, that I am gratified that I can be here for another reason, because I would like to say to all of you, as I have said from time to time when the opportunity presented, that I think one of your number—Francis Gary Powers— who has been criticized from time to time, I believe unjustly, deserves well of his country. He performed his duty in a very dangerous mission and he performed it well, and I think I know more about that than some of his detractors and critics know, and I am glad to say that to him tonight.”

Dulles’ talk was taped. Later “Kelly” Johnson had his remarks transcribed and a copy sent to me.

In April, 1965, I was asked to come back to Washington to be awarded the Intelligence Star.

My first reaction, quite frankly and quite bluntly, was to suggest they shove it.

We made the trip, however, for several reasons. It was less than two months before the birth of Gary, and would be the last opportunity to visit our families for some time. Following the ceremony, there was to be a dinner at Normandie Farms, Maryland, with a number of friends from the early days of the U-2 program in attendance, many of whom, including Bissell, I hadn’t seen in years.

I’m not sure why, having once declined the opportunity, it was decided to make the presentation in 1965. By this time McCone had submitted his resignation, and a Johnson appointee, retired Vice Admiral William F. Raborn Jr., was scheduled to be sworn in as DCI in little more than a week. Perhaps it was felt that this was a bit of leftover business to be gotten out of the way before the new DCI took over. At any rate, although the ceremony was impressive, it was cheapened for me not only by what had preceded it, but by the realization that the presentation was worded in such a way as to commend me for my “courageous action” and “valor” prior to 1960. Apparently it was felt the Virginia hillbilly wouldn’t catch such a subtlety, or notice, when I examined the scroll accompanying the medal, that the date on it was that of the earlier ceremony, April 20, 1963.

Word of the secret ceremony leaked to the press. The accounts were wrong in one particular, however. Instead of the actual April date, they said it occurred on May 1, 1965, the fifth anniversary of my flight.

That was, I’m quite sure, the last thing the agency wished to commemorate.

As is probably obvious from my account, I’m patient, unusually so, and always have been. While some might consider this a virtue, I think of it as a fault. But it’s the way I am, and try as I might, I haven’t been able to change it.

For a time I put thoughts of the book aside. My work, my family, our friends, were more than enough to fill my time. Too, more than a few of my recollections were not pleasant. I was not anxious to relive them.

And no man, even in the privacy of his innermost thoughts, likes to admit he has been used.

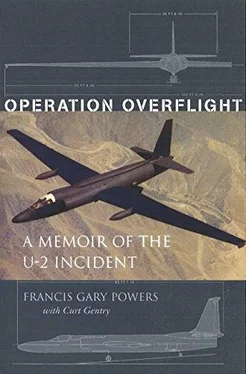

Meanwhile, other books dealing with the U-2 incident continued to appear, among them Allen Dulles’ The Craft of Intelligence , Harper & Row, 1963, which related the story of the exposure of the Russian bomber hoax; and Ronald Seth’s The Anatomy of Espionage , E. P. Dutton, 1963, which considered the U-2 flights in relation to the whole broad spectrum of intelligence-gathering.

In his chapter on the U-2 story, Seth did something a great number of others hadn’t. He studied the trial testimony, concluding: “Indeed, throughout the whole of his trial, [Powers] comported himself with a dignity and spirit which might have been found lacking in many another. All the way down the line, Powers was badly served—by his President and others who ought to have known better, by faulty intelligence which led him to believe that he was invulnerable, and by attempts just before the trial to accuse the Russians of having brainwashed or drugged him.”

One book of special interest was Lyman B. Kirkpatrick’s The Real CIA , Macmillan, 1968, for its glimpse of what happened in the inner chambers of the agency when realization dawned that I hadn’t made it to Bodo. It caused, according to Kirkpatrick, former executive director of the Central Intelligence Agency, “one of the most momentous flaps that I witnessed during my time in the federal government.”

Kirkpatrick’s account is not wholly uncritical of the handling of the affair. With remarkable understatement, he notes: “It was fairly obvious that the unit of the CIA that was responsible for the cover story had not thought the matter through very carefully.” He continues: “To my knowledge nobody has ever yet devised a method for quickly destroying a tightly rolled package of hundreds of feet of film. Even if Francis Powers had succeeded in pressing the ‘destruction button,’ which would have blown the plane and the camera apart, the odds would still have been quite good that careful Soviet search would have found the rolls of film.”

Yet this mistaken assumption—that the plane would have been totally obliterated, all evidence of espionage destroyed—apparently was believed at the highest level, by the President himself.

Kirkpatrick was in California at the time of Khrushchev’s shattering announcement. Cornered by reporters, his single comment was, “No comment.” He notes: “Later I was pleased to learn that one of the newscasters, in commenting upon the episode, characterized my statement as the only intelligent one made by the government during the event.” With that I am inclined to agree. From a strictly selfish viewpoint, my interrogations would have gone easier had there been a little less talk.

Kirkpatrick concludes: “The development and use of the U-2 was a remarkable accomplishment, and the fact that it came to the end of its starring role over Russia on May 1, 1960, should not dim the achievements of the men who made it possible…. Francis Powers, and the others who flew the plane, also deserve full credit for their courage and ability. Powers conducted himself with dignity during his interrogation and trial and revealed nothing to the Russians that they did not already know. Upon his return to the United States in 1962, after he was exchanged for Rudolf Abel, a review board headed by Federal Judge E. B. Prettyman went into the minute details of his conduct while a prisoner and found that he had conducted himself in accordance with instructions. He was decorated by the CIA.”

Читать дальше