In part, I was witnessing a vast organizational shake-up, due to President Kennedy’s vow to restructure the agency following the failure of the Cuban invasion. In a world of secrets, the least kept was that John McCone, although an astute businessman—according to the General Accounting office, his California shipbuilding company had turned a hundred-thousand-dollar investment into forty-four million dollars during World War II—knew little about intelligence. He was a political appointee, and, I now learned, Robert Kennedy’s personal choice as successor to Dulles. According to rumor, he was not the first choice. Although I found it difficult to believe—it has since been brought out in other accounts—Robert Kennedy had apparently wanted to take over as director of Central Intelligence, in addition to being attorney general, the idea being scotched because it would have lent fuel to the argument that the Kennedys were attempting to create a dynasty.

If true, it would provide another possible explanation for the story that he had wanted to try me. Powers could be made a symbol of the failure of the old order.

Maybe the shake-up was long overdue. Maybe the CIA had acquired too much independent power and needed to be brought under closer control of the President. I only knew what I saw— bureaucratic chaos. Divided loyalties. Jockeying for favor. A half-dozen people doing jobs previously done by one. Paperwork increasing at such a rate that one suspected the task of collecting intelligence could be dropped, with the paperwork alone sufficient to keep everyone occupied.

Undoubtedly only a portion of this was due to McCone. Perhaps what I was witnessing was simply that the CIA, having outgrown its youthful exuberance, was suffering the middle-age spread that seems to be the lot of most government agencies.

Admittedly I saw only part of the whole picture. But it bothered me.

Another thing also bothered me. Even within the agency many people were unsure of my exact status: had Powers been cleared, or hadn’t he? The people at the top knew, but hadn’t let the word filter down. I encountered no animosity, but I did find a great deal of puzzlement. The CIA clearance, with its evasive wording, had raised almost as many doubts as it had laid to rest.

My attitude toward this remains today much as it was then. I knew what I had and hadn’t done. I did not feel I had to clear my name. Nor did I feel I had to justify my conduct to anyone. People would have to accept me as is. Those who couldn’t, I wasn’t interested in having for friends. Fortunately, over the years the former have predominated.

Yet this did not mean that I was happy at having been placed in this position.

I enjoyed my work with the training section because I felt it was important. The tricks the Russians used in their interrogations, the difficulty of improvising a workable cover story, the decision of how much to tell and how much to withhold, how to avoid being trapped in a lie, how best to cope with incarceration—these were only a few of the problems we explored. I also read the accounts of other prisoners, pointing out where my experiences differed or were the same. And I consulted with the people in psychological testing to give them clues as to what to look for in screening certain covert personnel.

It was satisfying work—later I learned that a number of my suggestions had been incorporated into the training program for certain personnel—but I was also aware that it was temporary, something to do until such time as I could make some decisions. Not all of them concerning my future employment.

Nothing had changed with Barbara, except to grow worse. Again there were the suspicions: unexplained absences from the apartment; charges on the phone bill for long-distance calls I thought were in error but had been made to an unfamiliar number in Georgia; constant pleading to be allowed to go back there for a visit, although, estranged from her mother, she could never provide a good explanation for the necessity of such a trip. And the certainties: bottles under the bed, in closets, in dresser drawers. One night in April, following a familiar argument, in which I insisted that if she couldn’t stop drinking by herself she would have to have medical aid, she swallowed a whole bottle of sleeping pills. I rushed her to the hospital, just in time.

Following her recovery, I tried to get her to remain in the hospital for treatment of her alcoholism. But she refused; she still would not admit she was an alcoholic. I had hoped this close call would bring her to her senses, make her realize she needed competent help. It didn’t. Upon her release the situation remained unchanged. In May she simply packed a bag and returned to Georgia.

On returning from a trip to the West Coast, I stopped in Phoenix to see some friends. While deplaning I was paged to contact TWA for a message. Few people knew my itinerary; so I knew it was something out of the ordinary. Checking with TWA, I was given a local number to call; on calling it, I was given still another number, this one in Washington, D.C. The CIA agent who answered informed me that Barbara and a male companion had been in some kind of trouble at a drive-in restaurant in Milledgeville. Refusing to leave when asked to do so by the management, they had caused such a scene that police had to be called. By some means, word of the incident had reached the CIA. The situation had been resolved, but the agency felt I should know what had happened.

On arriving in Milledgeville, I laid down the law. She had to have medical help, had to leave Milledgeville, and had to stop seeing certain people, including her male companion. I was going back to Washington, I told her; if she wanted to accompany me, it would have to be under those conditions. Otherwise I was going alone and would take whatever action I deemed necessary. Believing this was just another empty threat, Barbara chose to stay in Milledgeville.

In August I returned to The Pound, ostensibly for a visit but really to think things through. When I did, I was forced to admit there was no helping Barbara, not without her agreement; that in continuing the marriage I was only holding onto the shell of what was and what might have been; all else was ashes—had been for a long time. Before returning to Washington, I took off my wedding ring.

Georgia was still my legal residence. Not long after this I returned to Milledgeville to consult an attorney. While there I asked the questions avoided since my return. The answers confirmed my worst suspicions while in prison. But now it no longer mattered. I filed suit for divorce. The decree became final in January, 1963.

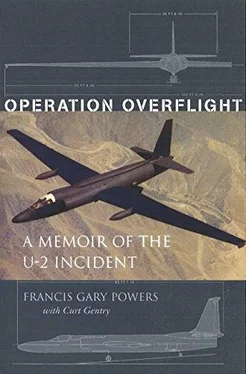

In May, 1962, I was given verbal permission to write the book. I was not informed as to who made the decision, but I was sure the request had gone all the way up to McCone, since no one else would be willing to take such responsibility.

Consulting with an attorney, I went through the offers, finally deciding on a joint proposal advanced by the publishing firm Holt, Rinehart and Winston and the Saturday Evening Post . Negotiations began and had reached the contract stage when, in early July, I was informed, again verbally, that upon reconsideration it had been decided that a book at this time would not be advantageous either to me or to the agency. While they could not forbid me to publish the book, they strongly suggested that I not do so.

Word had filtered down through several levels. However, it was clear that the decision to grant permission had been vetoed by someone higher up than McCone. That left few possibilities.

A good amount of time and money had been spent on the negotiations, and a number of people inconvenienced. I didn’t like that. Neither did I appreciate the implication that I might be adversely affected if the truth were told.

Читать дальше