Yet I also felt something else, something perhaps only a person who has spent time in prison can fully comprehend. I was deeply grateful to the agency and to the government for effecting my release. They could just as easily have left me in prison until May 1, 1970, had I lived that long. In a sense, each day of my freedom before that time I owed to them.

That that freedom was to be qualified, however, that silence was the price I would have to pay for it, was not a pleasant realization. Especially when I suspected that the chief motivation behind the decision was political, the fear that what I had to say might embarrass the agency.

I spent the weekend of the Fourth of July trying to decide what to do.

On July 6 I wrote the following letter:

Dear Mr. McCone:

Recently there has been communicated to me your views concerning my intention to publish an account of my personal experiences preceding, during, and after my imprisonment by the Russian government.

While you have been correctly informed that I have been negotiating with interested publishers with a view toward publishing my personal account, I wish again to dispel any doubts concerning my initiating these negotiations without prior consultation. The invitations to discuss the publishing of my experiences were received from various publishers both before and immediately upon my return to the United States. These invitations were directed not only to me but to various agency officials, including yourself. I made no effort to discuss these offers until I had been advised that there was no objection on the part of the agency or the government to my doing so. While I did not expect any encouragement in this matter, I am distressed that I was misled in believing there was no objection.

I understand now that you are of the opinion that in view of the public acceptance of the presentation of my account to the Senate Armed Services Committee, any further effort by me to comment in extenuation of my experiences would only result in possible injury to the agency and to myself.

I will, therefore, accept your feeling on this subject, and although I am not persuaded by the logic thereof, I will abide by your desires not to publish a book on my experiences at this time. I would be less than candid if I left the impression that I am taking these steps willingly. I am not, however, unmindful of the great effort which was made by the government to obtain my release from imprisonment, and am most grateful for this interest in my behalf. Accordingly, I am advising those publishers with whom I have been negotiating and who have shown an active interest in publishing my experiences that I will not entertain any further consideration of their offers.

Very truly yours, Francis Gary Powers

I had been muzzled. It was only then that I began to have doubts whether the story would ever be told.

My decision to leave the Central Intelligence Agency was motivated by three factors:

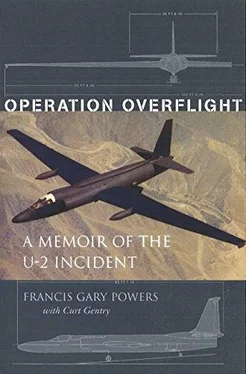

1. Suppression of the book, to which I had reluctantly acquiesced. Already one book, the first of several on the U-2 incident, had appeared, its authors, so far as I knew, having made no attempt to contact me.

2. The obvious fact that I was just killing time. Though I had my own office, with the implication that I could stay on at the agency as long as I wished, I had run out of meaningful work.

3. I was itching to fly.

With nearly twelve years of service, and only a little more than eight to go until retirement, I couldn’t afford not to go back into the Air Force. Yet I still wasn’t ready to lead a regimented life: I wanted to be able to go where I pleased, do what I wanted to do. On checking with the Air Force, I was told there was no hurry as to a decision; I could take my time.

One of my friends at the agency knew “Kelly” Johnson and offered to call him to see if the job at Lockheed was still open. Johnson suggested I fly out to California and talk to him. In September, 1962, I did so.

I was about ready to say I was interested only in a flying job when he asked: Would you like to be a test pilot?

I suspect that at one time or another this has been almost every pilot’s ambition: I knew it was mine. I said I would.

Flying U-2s?

The answer was written across my face in a big grin.

On returning to Washington, I submitted my resignation to the CIA, and reported to work at Lockheed on October 15, 1962.

By this time the U-2 had proven itself again. While at the agency, I had kept abreast of developments in the program, and was aware that Air Force pilots, under the command of SAC, were making overflights of Cuba. I also knew that late in August a U-2 had spotted a number of Soviets SAMs, probably similar to the one that brought me down. What no one knew for certain, however, until a U-2 returned from its overflight along the western edge of Cuba on October 14 and its photographs had been processed and studied, was that sites were being built for medium-range ballistic missiles capable of reaching targets in the United States.

We were to pay a high price for our intelligence on the Cuban missile crisis. While overflying Cuba, USAF Major Rudolph Anderson was shot down by a Soviet SAM.

With his death, no one could any longer doubt that Russian missiles were capable of reaching the U-2’s altitude.

My work at Lockheed was as an engineering test pilot. This consisted of test-flying the planes whenever there was a modification, a new piece of equipment installed, or the return of an aircraft for maintenance.

Getting back into the tight pressure suit was an odd sensation— uncomfortable as ever. But there was one improvement. It had been found that an hour of prebreathing prior to flight would suffice. Again I was back in the high altitudes. Perhaps needless to say, my insurance premiums rose even more astronomically.

Except for a few close calls, I thoroughly enjoyed the work. Two times hatch covers blew out. One knocked a hole in the wing and in the tail. The other jammed the canopy so I couldn’t get out. But each time I managed to make it back. And, while I was working at high altitudes, where the aircraft was most temperamental, there were, I’ll frankly admit, occasions when I was scared. But my confidence in the U-2 remains unshaken. It was and still is a remarkable aircraft, one of a kind.

I only wish there were more of them around.

In 1963 I received the first of what was to be a number of rude awakenings.

You’re going to have to make up your mind, Powers, the general said. If you want to go back into the Air Force, you’ll have to do it soon.

With nearly twelve years toward retirement—

Five and a half, he corrected me. Your time in the CIA won’t count.

On joining the U-2 program in 1956 I had signed a document, cosigned by Secretary of the Air Force Donald A. Quarles, promising me that upon completion of service with the agency I could return to the Air Force with no loss of time in grade or toward retirement, my rank to correspond with that of my contemporaries. This had been a major factor in my accepting employment with the CIA. The same was true of the other pilots, all of whom had signed the same document. A number of them had already returned to the Air Force under those conditions.

The general knew this. But there had been too much publicity about my case. Although they would let me reenlist at comparable rank—an old captain, or a new major—they would have to renege on their promise regarding my CIA service counting as time toward retirement.

I was being penalized for doing my duty, for having spent twenty-one months in a Russian prison!

He was sorry, but that was the way things were.

I could have fought it, I suppose. However, as with my agency contract and numerous other documents I had signed, the CIA retained the only copy. To contest this, I would have to use other pilots as witnesses. Some of them, I was quite sure, wouldn’t lie. But it would be damn rough on them. My attempt to obtain what I had been “guaranteed in writing” might mean the Air Force would penalize them, too.

Читать дальше