My problems were by no means unique. Like any returning veteran, I needed time to adjust, wasn’t anxious to make any big decisions, at least not yet.

I left the hospital with all my problems intact. As for the checkup, it had only revealed what I already knew, that one souvenir of my sojourn in Russia was a bad stomach condition which I would probably have for the rest of my life.

Ironically, most of the foods I had dreamed about eating while I was in prison in Russia, I now couldn’t have.

This particular souvenir caused me trouble until 1968, at which time—after Lovelace Clinic and others had failed to alleviate the condition—a private physician prescribed medication that immediately relieved the pain. Only during the past two years have I been able to eat salads, corn, and sundry other foods I so missed. The condition remains, however; one day off the pills, and the symptoms come back. Imprisonment may be an effective method of diet, but I don’t recommend it.

Two men from the agency drove me to The Pound. I had expected they would remain, but to my surprise they returned to Washington. I was finally on my own.

Lonely I was not. My sisters, their husbands and their children, plus more relatives than I knew I had, attended the homecoming. Some eight-hundred people crowded into the National Guard Armory at Big Stone Gap, Virginia, to witness the VFW award ceremony. There were two high-school bands. Beside me on the platform sat my mother and father. This was really their day. More than any other single person, my father could claim credit for effecting my release, by first suggesting the trade for Abel. I was immensely proud to see him receive his due.

On my own initiative, rather than instructions from the agency, I had decided if possible to avoid the press. However, when it’s raining, the roads have turned to mud, and cars are stuck outside your front door with no one else to help pull them out, what can you do? Too, they had gone to the trouble of driving all the way to The Pound, and it seemed unfair not to see them. One, Jim Clarke of radio station WGH, Newport News, Virginia, arrived about eleven o’clock the night of the award ceremony. Most of the family had already gone to bed exhausted. After some persuasion, I consented to tape an interview which was broadcast a few days later. As with the other reporters, I told him little more than I had told the Senate. Although Clarke was pleasant and did his best to put me at ease, his interview had one bad aftereffect. At one point I stated I “thought” I had seventy seconds on the destruct device. As mentioned earlier, not all of the timers worked uniformly, some with a variance of as much as five seconds either way. Tired after the long emotional day, my mind blanked. I couldn’t remember exactly how accurate this particular timer might have been.

Later, at least one reporter picked up that qualifying word and used it to resurrect the whole conspiracy theory first proposed by the Soviets, that is, that the pilots weren’t sure they had a full seventy seconds; they were afraid the CIA had rigged the device to explode prematurely, killing them too.

After that I refused all interview requests. I felt—with some justification, I believe—no small amount of resentment toward at least some members of the fourth estate, particularly those who had presumed to try me in absentia before all the facts were in and when there was no way I could defend myself.

While in The Pound I saw McAfee, my father’s attorney, and asked him about the two-hundred-dollar fee demanded for an interview with Kennedy. McAfee refused to identify the person, however. He would say only that it was someone in the White House. I had no choice but to leave it at that.

From The Pound I went to Milledgeville, Georgia, to pick up Barbara. By this time I had decided to accept the CIA’s offer, at least until such time as I could make up my mind as to what I wanted to do.

I had been in Milledgeville only a short time before I sensed a strong hostility toward Barbara there. She explained it was because she was a “celebrity”; people resented her fame. But I felt something else on coming into contact with residents: pity, not for Barbara but for me. It was as if everyone knew something I didn’t and felt sorry for me. I didn’t like that a bit. Fortunately, our stay was brief. On returning to Washington, we found an apartment in Alexandria and I went back to work for the CIA, grounded in the first nine to five job I’ve ever had in my life.

Since my return I had received a great deal of mail, some sent in care of my parents, but much of it directed to me at the CIA. Of several hundred letters, only a few were critical. Most were warmly congratulatory. I heard from friends not seen since boyhood, pilots I’d last seen in the service. The majority, however, were from people I had never met, many from mothers who had prayed for my release. And there were some surprises, among them a letter from Cardinal Spellman, thanking me for coming to his defense during my trial.

As surprising were the large number of offers to buy the rights to my story. On reporting to work at the agency there was a whole sheaf of telegrams and urgent telephone messages. One book publisher, wasting no time on preliminaries, offered a flat $150,000 advance.

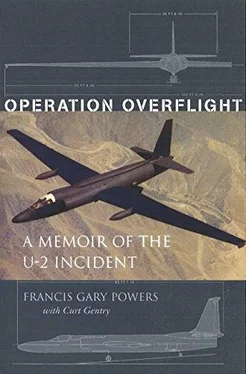

Thus far my side of the story hadn’t been told. Because of national security, I realized it might be years before some aspects could be made public. However, there was much that could—no, should — be known, if for no other reason than to avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future. For mistakes had been made, bad ones. The U-2 incident was an almost classic textbook case of unpreparedness. Too, the story told the American people was heavy with lies and distortions. This seemed a good way to set the record straight. I made inquiries within the agency as to whether there would be any objection to my writing a book about my experiences. I realized it would take some time for the request to travel up the chain of command, but was prepared to wait.

At the same time, I also asked if I could write to my former cellmate. The answer came back quite promptly. Negative. It would look bad if anyone found out you were writing someone inside Russia.

Though I abided by the decision, it was less for this reason than another. I didn’t want to cause Zigurd any trouble. And there was just a chance that by writing to him I might do so.

Admittedly, my previous experience with the agency had spoiled me. I had been part of a select, smoothly functioning team of experts who had a job to do and did it, with a minimum of fuss. As such, I had seen only glimpses of the actual organizational structure of the CIA. They were enough, however, to convince me that things had now changed.

By this time both Dulles and Bissell had left, the latter offering his resignation as deputy director of plans just seven days after my release. Bissell had survived the U-2 episode, but not the Bay of Pigs, becoming just one of the scapegoats for that tragic fiasco. Controversy over it was still raging within the agency. The plan had been good but poorly executed. It never would have worked. Kennedy was responsible for its failure by withdrawing air support. Kennedy had never authorized air support in the first place, therefore couldn’t have withdrawn it. So the arguments went.

Although a year had passed, everyone still seemed to be searching for someone else on whom to pin the blame.

Maybe I was naïve. Maybe it had always existed without my noticing it. But politics now seemed to dominate the agency, almost to the exclusion of its primary function, collecting intelligence. Everything had to be justified, especially in the light of how it might appear in the press. Decisions were avoided because of possible backlash if they proved wrong (though this was not new to me with my military background). Concern appeared to be less with what the facts were than with how such information would be accepted. And it takes little insight to realize that when intelligence is shaped to be what its recipients want to hear, it ceases to be intelligence.

Читать дальше