As we drove to the Old Senate Office Building, I scanned the list. What part of Virginia are you from? Where did you attend grammar and high school? Where did you go to college? I was admittedly shy; the mere thought of appearing before a large crowd frightened me. This little bit of prebriefing was helpful, and I was thankful to Russell for being so considerate.

We made it out of the automobile and into the building without being spotted. But as we were walking down the corridor to the Senate caucus room, one of the TV reporters recognized me. Within seconds the cameras were focused and questions were coming from every direction.

I thought: This is the first time I’ve ever been on TV! But, before I could panic, I remembered: No, it isn’t. There was Moscow. You should be a seasoned performer by now.

Powers can’t make any statement at this time, my escort insisted, trying to hurry me past. Would I talk to them after the hearing ended? I promised to do so.

There were about four hundred people in the Senate caucus room. Including Chairman Russell, fourteen senators were present: Harry Flood Byrd, Virginia; John Stennis, Mississippi; Stuart Symington, Missouri; Henry M. Jackson, Washington; Sam J. Ervin, Jr., North Carolina; Strom Thurmond, South Carolina; Robert C. Byrd, West Virginia; Leverett Saltonstall, Massachusetts; Margaret Chase Smith, Maine; Francis Case, South Dakota; Prescott Bush, Connecticut; J. Glenn Beall, Maryland; and Barry Goldwater, Arizona.

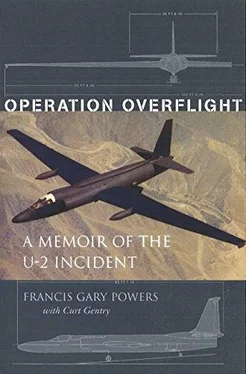

As I sat down at a table, facing them, someone handed me a model of the U-2, and I held it while the flash bulbs snapped. Promptly at two P.M. the chairman called the hearing to order.

Chairman Russell began: “That will be all for those cameras. I will ask the officers to see that rule is enforced and that no further pictures are taken. If you need any additional policemen for that purpose, we will summon them.

“The Armed Services Committee, through the Central Intelligence Agency, has extended to Mr. Francis Gary Powers an invitation to appear in open session this afternoon.

“Before we hear from Mr. Powers, the Chair would like to make a very short statement concerning the circumstances of this hearing.

“The Chair believes it can be fairly stated that this committee and its subcommittees have attempted to deal with subjects involving the Central Intelligence Agency and, indeed, all matters affecting the national security, in an unspectacular manner.

“Accordingly, to some, it may appear that this hearing in the caucus room, under these circumstances, is somewhat uncharacteristic of the proceedings of this committee.

“In this instance, however, the correction of some erroneous impressions and an opportunity for Mr. Powers to reveal as much of his experience as is consistent with security requirements make it apparent that a hearing of this type at this time is not only in the national interest, but is in the interest of fair play for Mr. Powers….

“Mr. Powers, after having been subjected to a public trial in Moscow, you should feel no trepidation whatever in appearing before a group of your fellow citizens and elected representatives. I hope that you feel just as much at ease as you possibly can.

“I understand from Senator Byrd that you are a Virginia boy. What part of Virginia are you from?”

After the initial questions, Chairman Russell asked me to tell, in my own words, exactly what had happened on May 1.1 did, describing the prebreathing, the last check of the maps, my final instructions from Colonel Shelton, and the delayed takeoff—but omitting mention that this had been occasioned because we were awaiting White House approval. Then I described the flight itself, seeing the jet contrails below and realizing I had been radar-tracked, the autopilot trouble, the route—but again omitting certain things, such as how I made my radio fixes, that this would be the first time a U-2 had overflown Sverdlovsk. Although I was accompanied by Lawrence Houston, general counsel for the Central Intelligence Agency, there had been no prior briefing by the agency on what I should or should not say. Apparently by this time it was presumed I knew what was and wasn’t sensitive. All I could do was guess, hoping some of these matters had been earlier covered by McCone.

Interrupted only for occasional clarification by Russell, I then described in considerable detail the orange flash and what had followed, up to my final unsuccessful attempt to activate the destruct switches. From the faces of the senators I couldn’t tell whether or not they believed me. All I knew was that I was telling the truth.

I went on to tell of my descent and capture, the trip to Sverdlovsk, the bringing in of my maps and assorted wreckage, the questioning, my decision to admit that I was employed by the CIA, the trip to Moscow, Lubyanka Prison, and the interrogations. Realizing that I had been talking for what seemed a very long time, I paused and observed that they probably had many questions.

Russell had several. I had been vague as to time. Didn’t I have a wristwatch? No, I replied, explaining that because of the difficulty of putting it on over the pressure suit, I didn’t wear one. Had I ever experienced a jet-plane flameout? Yes, and there was no comparison.

CHAIRMAN RUSSELL: Has there ever been any other occasion when you were in an airplane and were the target of a ground-to-air missile or explosive or shell of any kind?

POWERS: Not that I know of.

CHAIRMAN RUSSELL: YOU have never seen any ground-to-air missile explode?

I replied that I hadn’t, although I had seen motion pictures of such happenings, adding, “I am sure that nothing hit this aircraft. If something did hit it, I am sure I would have felt it.”

I’d had twenty-one months to think about this question and was convinced—as were “Kelly” Johnson and others—that the plane must have been disabled by the shock waves from a near-miss. Had it been a direct hit, I doubted seriously whether I would be here testifying before the Senate.

While I was talking, one of the Senate pages handed me a white envelope. I slipped it into my pocket and promptly forgot it.

CHAIRMAN RUSSELL: I wish you would clear up the matter of the needle, Mr. Powers. Were you under any obligation to destroy yourself if you were captured?

POWERS: Oh, no. I don’t remember exactly who gave me the needle that morning, but they told me, “You can take it if you want to.” They said, “If something does happen, you may be tortured. Maybe you could conceal this on your person in some way, and if you see that you cannot withstand the torture, you might want to use it.” And that is the reason I took the needle. But I could have left it. I wasn’t told to take it.

CHAIRMAN RUSSELL: DO you have the instructions that you received that morning and that you usually received before you—

Russell stopped abruptly, realizing he had almost mentioned my other overflights.

He was referring to the three paragraphs in the CIA clearance regarding what I was to do in the event of capture. On his instructions, I read them into the record.

Russell then questioned me about the red-and-white parachute I had seen. Earlier, when this had been brought up during the debriefings, one of the agency intelligence men had told me there was evidence indicating that in their attempt to get me the Russians had also shot down one of their own planes. I wasn’t told the source of this information, only that from contacts within Russia they had learned about the funeral of a fighter pilot who presumably had piloted the aircraft.

This fit in with what I had suspected.

However, since this was an area which might be sensitive— involving, as it did, our intelligence apparatus within Russia—and because, too, my information on this was secondhand, I didn’t mention it to the committee. I did observe that the second chute was not a part of my equipment.

Читать дальше