After the war, flights continued, but on a random basis, chiefly to watch for new military buildups along the borders.

Nor were we interested only in Egypt and Israel. If there was a trouble spot in the Middle East, the U-2s observed it. If a spot turned hot, we’d overfly it, frequently. Once it had cooled down, there would be only occasional missions, to watch for unusual activity. We checked on Syria, whether there was an outbreak of hostilities or not, to keep an eye on its critical oil pipelines. Iraq, another trouble spot, received periodic attention, as did Jordan. Saudi Arabia was of lesser interest. However, since it was along the way, we overflew it also, our route taking us over both the capital, Riyadh, and Mecca. Skirmishes between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots were silently witnessed, as was the heavy fighting between Lebanese Army troops and Moslem rebel forces in 1958. During 1959, when disorders broke out in Yemen, I flew a mission there. It was a memorable flight, not only for the distance covered—it was about as far from Turkey as the U-2 could fly and return—but also because I encountered several varieties of trouble en route. One was a violent thunderstorm, the worst I had ever seen, which obscured our objective. For a while I was unaware whether I could fly above it, it extended so high. The other occurred on the way down. My flight line called for me to remain over the land side of the Arabian coast; on looking in my mirror, however, I saw condensation trails behind the aircraft, until that time unheard of at our altitude. Realizing I could be spotted from the ground, I moved out over the Red Sea, over what I presumed could be claimed as international waters. Then, by slowing down, I managed to climb a little higher to see if the contrails would go away. To my relief, they did.

These were the “special” missions. They began in the fall of 1956 and continued into 1960. If any of the U-2 flights merited the label “milk runs,” it was these. Such flights lacked the tension of the overflights. No one was shooting at us. Presumably no one was aware of our presence. Had we been forced to crash-land, we could always explain that we had been flying over the Mediterranean and had come down in the closest place, a believable story so long as the equipment and photographic films weren’t examined. Fortunately, there were no crash landings.

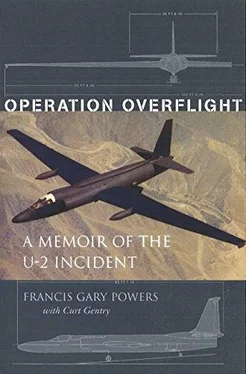

The primary mission of the U-2s was overflying Russia. This was the enemy, the greatest threat to our existence. In importance, the overflights—infrequent as they were—outranked anything else we did, and were the major reason for our presence in Turkey. The border surveillance and the atomic sampling, though vital, were secondary. Although they made up the bulk of our flying, in intelligence value the “special” missions took last place.

In terms of propaganda value to the Russians, however, the order was exactly reversed. We were fairly sure they knew about most if not all of the overflights. What they had no knowledge of were the “special” missions. Of all the information I withheld, this was the most dangerous, because of what the Russians could do with it.

It requires little imagination to conceive the devastating effect on America’s foreign relations had Khrushchev been able to reveal that the United States was spying not only on most of the countries in the Middle East but also on her own allies.

After considerable thought, I decided that unless Prettyman worded his questions in such a way as to indicate prior knowledge of the subject, I would mention neither this nor other sensitive matters.

This was part of the problem. The other part was psychological. The debriefings had been informal, held in the “safe” houses with people I knew had been cleared by the agency. During these, I had been completely honest in my replies, withholding nothing; yet, even then, I had often found myself hesitating before giving answers. For twenty-one months my interrogators had been the Enemy. Almost automatically, a question put me on the defensive. Although the board of inquiry was held in a conference room in CIA headquarters with several friends, including Colonel Shelton and another pilot, among the dozen or so persons in attendance, the semiofficial nature of the proceedings put me once more in this frame of mind. It was a hard habit to break.

After the first several questions I found myself disliking Prettyman; since he was a not unkindly-looking, white-haired old gentleman, this was probably due in large part to my preconditioning. I wasn’t evasive. When asked why I had told the Russians my altitude, I answered that sixty-eight-thousand feet wasn’t my correct altitude, told him what my actual altitude was, and explained what I had hoped to accomplish with the lie. But then neither did I go out of my way to educate him in all aspects of the U-2 program.

I’ve often wondered, in the years since, whether I made the right choice.

Prettyman, on the other hand, did nothing to put me at ease. Some of his questions bordered on the accusative. Several times he indicated, less in actual words than manner, that he had doubts about my responses. On one of these occasions, after some question so minor I’ve now forgotten it, I finally reacted angrily, bellowing, “If you don’t believe me, I’ll be glad to take a lie-detector test!”

Even before the words were out of my mouth, I regretted saying them, I had sworn, after the first polygraph examination, that I would never take another.

“Would you be willing to take a lie-detector test on everything you have testified here?”

I knew that I’d been trapped. From the way he quickly snapped up my offer, I felt sure that he had purposely goaded me into making it.

What could I reply? I wanted very much to say no, as emphatically as possible. But to do so would be the same as admitting I had been lying. Which was not true.

“Yes,” I replied, most reluctantly.

Shortly after that the hearing was concluded. It had lasted only part of a day, but had accomplished what I was now sure was its principal objective. The agency could tell the press that Powers had volunteered to take a lie-detector test.

That evening the agency brought Colonel Shelton and the other pilot out to the “safe” house for dinner. It was a jolly time, with lots of reminiscences.

I apologized to Shelton for using his name so freely, explaining that I had wanted to minimize the number of people compromised. He said he had realized what I was up to when he learned he was running the detachment all by himself. Still I could not help feeling sorry for having placed the burden on him, especially when he described the desolate base to which he had been ostracized.

It was an easy, relaxed evening, in a sense the first such since my return to the United States.

The polygraph test was no easier the second time around. If anything, it was worse, because you anticipated. Still, some of the questions caught me off guard:

“Do you have any funds deposited in a numbered Swiss bank account?”

“Did anything happen in Russia for which you could be blackmailed?”

“Are you a double agent?”

Fortunately, the polygraph operator—the same man who had given me my initial test in the hotel room in 1956—was an expert. He could tell the difference between a reaction activated by anger and one caused by a lie. Because I did react, strongly, to the implications behind such questions.

Excepting only breaks for coffee and lunch, I was “on the box” the full day. When the last electrode came off, I made no vows. I’d done that once. Superstitiously, I wasn’t going to make that mistake again.

As before, I wasn’t told whether or not I had “passed.”

Since my return there had been mounting pressure for a public hearing before Congress. I had hoped the Prettyman report, when released, would clear up all doubts, but realistically I knew it wouldn’t. Having been subjected to a series of official cover stories, which, one after another, had been exposed as fiction, the American people would not be inclined to accept the CIA’s assurances that I was “clean.” Therefore I wasn’t too surprised when I was told that arrangements had been made for me to appear in an open hearing before the Committee on Armed Services of the United States Senate on March 6. The Prettyman report would be made public shortly before this. In addition, the DCI, John McCone, would appear before the committee, in closed-door session prior to my appearance, to brief the senators on those aspects of the incident which were still classified. The President had already stated that I would reveal only that information “in the national interest to give.”

Читать дальше