Yet surely some who read that editorial believed it, felt I was not only a traitor but also a murderer.

After reading such nonsense, I was thankful the agency was keeping me from a face-to-face encounter with the press. It might have made headlines of a different sort.

Not all the fictions were a result of “imaginative reporting.” Some person or persons in the government had been responsible for the dissemination of more than a few. One was the story which had bothered me so much in Russia. I now learned that the editor of an aviation journal had stated on an NBC-TV White Paper on the U-2 that he had been assured by totally reliable government sources that the U-2 had not been hit at sixty-eight-thousand feet but, suffering an engine flameout, had descended to thirty-thousand feet, at which point it was shot down. U.S. intelligence knew this, he said, because (1) I had radioed this information; and (2) the entire flight had been tracked on radar. The story was certainly a nice plug for the effectiveness of our radio and radar. The only trouble was, both claims were not only not true, they were also not possible.

My early suspicions were not certainties. There were some people in the government absolutely refusing to accept the fact that Russia had surface-to-air missiles capable of hitting high-flying aircraft.

It wasn’t until much later, in 1965, with the publication of President Eisenhower’s memoirs, that I was to learn how far up the chain of command this misapprehension apparently extended.

“HERO OR BUM?” asked one newspaper. “Many questions need answering, not the least of which involve Powers’ own conduct,” noted another. “Should he, like Nathan Hale, have died for his country?” queried Newsweek .

I stopped reading the newspapers and news magazines. Yet it wasn’t that easy. For by this time I had heard, from several people in the agency something even more disturbing. Negotiations for the Abel-Powers trade had begun under William P. Rogers, Eisenhower’s attorney general. The current attorney general, Robert F. Kennedy, had opposed the trade. Moreover, he had said that upon my return to the United States he personally intended to try me for treason.

For God’s sake, why? I asked the people from the agency. As the President’s brother, he was certainly aware of the true facts of the case, including the importance of the information withheld.

There was no clear-cut answer, only conjecture. Rumor had it that, reacting to criticism of his appointment as attorney general when he had never actually practiced law, Robert Kennedy had wanted to “prove himself” with a spectacular trial.

I felt there must be more to it than that.

They were the experts. They knew what was important and what wasn’t. Yet as the debriefings continued—we had by this time moved to a third “safe” house, near McLean, Virginia, not far from Hickory Hill, the Kennedy estate—I couldn’t help feeling disappointed by their lack of thoroughness, the questioning being neither so intensive nor the queries so probing as I had anticipated.

It seemed to me that some of the information I possessed— concerning what I had observed on the May 1 flight and subsequently during my interrogations, trial, and imprisonment—was of intelligence value. For example, that the KGB had asked me some questions and not others seemed significant, as did whether the question was general or specific, was in the nature of a “fishing expedition” or indicated prior detailed knowledge. Such things, I felt, were important clues as to how good their intelligence was, and, though only bits and pieces, might be helpful in constructing a composite picture of the extent of their knowledge.

But the agency apparently felt otherwise. In this, as with other areas I thought important, they showed little interest.

They were far more concerned about what I had told the Russians regarding some of their other clandestine operations, and greatly surprised to discover that quite often I knew little or nothing about them.

There were many questions I felt should have been asked—but weren’t. Yet when I attempted to volunteer information, often as not it wasn’t appreciated. For example, while being questioned about the KGB officials with whom I had come into contact, I was shown a photograph of Shelepin, head of the KGB, and asked if I could identify him. But when I volunteered that it was Rudenko, not Shelepin, who appeared to be the “big wheel” in the interrogations, the man to whom the others deferred, they quickly passed on to something else. Maybe this wasn’t important. Yet, for a comparable example, if in the interrogations of a Soviet spy FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover played a superior role to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, I suspect the KGB would have been greatly interested in that fact.

One of the reasons I had kept the journal was to record things I felt might later be of use to the agency. When I told them about the journal, however, they expressed no desire to see it. I had assumed they would be interested in the fate of their former agent Evgeni Brick. From their reactions I got the distinct impression that they couldn’t have cared less. I had presumed they would communicate my information regarding Zigurd Kruminsh to the British, since he had been a British agent. If they did, there was no follow-up.

From the start, it was obvious they believed my story. The “Collins” message had gotten through. As had the repeated references to my altitude. And, from the simple fact that certain things hadn’t happened which would have happened had I told the Russians about the “special” missions, they realized I hadn’t told everything. I was pleased that they believed me. Yet I remained disappointed in the debriefings. It may be that the information I possessed was worthless. The only way to determine that, however, was to find out what I did know, then evaluate its importance or lack of it. Instead they seemed to have decided in advance what they were interested in, which—to me, at least—seemed a rather faulty intelligence practice. And considering the questions, I couldn’t help discerning an obvious pattern behind them: that the agency was not really interested in what I had to tell them; their primary concern was to get the CIA off the hook.

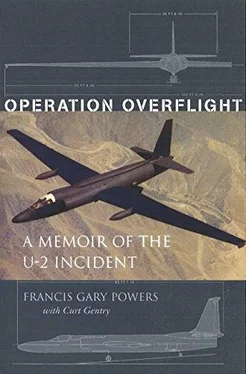

If true, this was not the first attempt to pass the buck, to pin the blame elsewhere. Shortly after my return, on coming into contact with several former participants in Operation Overflight, I heard a most disturbing story.

When I had failed to appear at Bodö, Norway, the ramifications had hit Washington like a burst of flack. I had gone down somewhere in Russia: there could be no other explanation. Yet, because number 360 had a fuel-tank problem, this didn’t necessarily mean I had been shot down, and, since Russia was a very large country, it could be that the plane wouldn’t be found. In any event, it was unlikely the pilot was still alive.

A contingency plan was hastily drawn up, for use in the event the Russians should have the wreckage of the plane and decide to make an issue of it.

The plan was quite simple. One of the higher-ranking agency representatives at Adana, a man whom we’ll call Rick Newman, would confess to overzealously taking it upon himself to order me to make the flight, with no authorization whatsoever. Thus, by blaming a “gung-ho” underling, the President and the CIA could evade admission of responsibility.

The reason for their settling on Newman and not Colonel Shelton was obvious: they needed a civilian, so the Russians couldn’t term it a military operation.

As preparation for putting the plan into effect, Newman was secretly flown from Turkey to Germany and hidden in the basement of the house of our agency liaison there, to make sure he couldn’t be reached by reporters.

Читать дальше