Nervous as I was before crowds, I was not looking forward to the hearing, except that it would mean the end of my ordeal and, hopefully, the slanders, which I knew deeply hurt my family. They had been forced to live through the stigma of having people brand me a traitor. Barbara, however, had no intention of staying for my “vindication” or whatever might result. She wanted to go home to Georgia. Over the past several weeks she had grown increasingly restless. The reason was obvious—my insistence that she cut down her drinking, and the security measures in effect at the “safe” house, made it impossible for her to get all the liquor she wanted. Against my better judgment, I agreed to the trip, promising to meet her in Milledgeville after the Senate hearing and a brief homecoming visit to The Pound.

The latter was to include a community-wide celebration, during which I was to be awarded the American Citizenship Medal by the Veterans of Foreign Wars. That this had been planned long before the people of Virginia knew whether I had or hadn’t been cleared was a welcome vote of confidence.

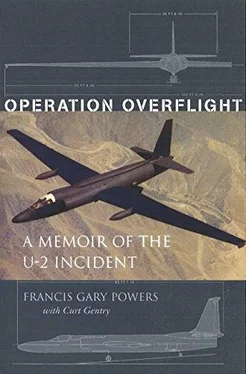

“STATEMENT CONCERNING FRANCIS GARY POWERS.”

Released to the press just prior to the Senate hearing, my “clearance” consisted of eleven typewritten pages. It began: “Since his return from imprisonment in Soviet Russia, Francis Gary Powers has undergone a most intensive debriefing by CIA and other intelligence specialists, aeronautical technicians, and other experts concerned with various aspects of his mission and subsequent capture by the Soviets. This was followed by a complete review by a board of inquiry presided over by Judge E. Barrett Prettyman to determine if Powers complied with the terms of his employment and his obligation as an American. The board has submitted its report to the director of Central Intelligence.

“Certain basic points should be kept in mind in connection with this case. The pilots involved in the U-2 program were selected on the basis of aviation proficiency, physical stamina, emotional stability, and, of course, personal security. They were not selected or trained as espionage agents, and the whole nature of the mission was far removed from the traditional espionage scene. Their job was to fly the plane, and it was so demanding an assignment that on completion of a mission, physical fatigue was a hazard on landing.”

It took the CIA just two paragraphs to get itself off the hook, to gloss over the fact that we were almost totally unprepared for the possibility that one of the U-2s might go down in Russia.

What followed interested me greatly.

“The pilots’ contracts provided that they perform such services as might be required and follow such instructions and briefings in connection therewith as were given to them by their superiors. The guidance was as follows:

“a. If evasion is not feasible and capture appears imminent, pilots should surrender without resistance and adopt a cooperative attitude toward their captors.

“b. At all times while in the custody of their captors, pilots will conduct themselves with dignity and maintain a respectful attitude toward their superiors.

“c. Pilots will be instructed that they are perfectly free to tell the full truth about their mission with the exception of certain specifications of the aircraft. They will be advised to represent themselves as civilians, to admit previous Air Force affiliation, to admit current CIA employment, and to make no attempt to deny the nature of their mission.

“They were instructed, therefore, to be cooperative with their captors within limitations, to use their own judgment of what they should attempt to withhold, and not to subject themselves to strenuous hostile interrogation. It has been established that Mr. Powers had been briefed in accordance with this policy and so understood his guidance.”

My actual instructions, obtained only after I had brought the issue to the fore, were much more concise: “You may as well tell them everything, because they’re going to get it out of you anyway.”

There was no indication in the wording that I had failed to heed this suggestion or gone far beyond what I was required to do.

“In regard to the poison needle,” the statement continued, “it should be emphasized that this was intended for use primarily if the pilot were subjected to torture or other circumstances which in his discretion warranted the taking of his own life. There were no instructions that he should commit suicide and no expectation that he would do so except in those situations just described, and I emphasize that even taking the needle with him in the plane was not mandatory; it was his option.”

I was glad to have that on record. And I was not displeased by what followed.

“Mr. Powers’ performance on prior missions has been reviewed, and it is clear that he was one of the outstanding pilots of the whole U-2 program. He was proficient both as a flyer and as a navigator and showed himself calm in emergency situations. His security background has been exhaustively reviewed, and any circumstances which might conceivably have led to pressure from or defection to the Russians have also been exhaustively reviewed, and no evidence has been found to support any theory that failure of his flight might be laid to Soviet espionage activities.”

Though I was unaware of it at the time, that last statement was open to question. As will be noted, there did exist some rather astonishing circumstantial evidence which indicated that my flight may have been betrayed before I even lifted off the ground.

As for the exhaustive review of my background, I had learned of this during the debriefings, from one of the men conducting the investigation. “I’ll bet we know more about you than you know about yourself,” he remarked, adding, “The amazing thing is how clean you came out. I’ve been doing this sort of thing for a long time, and you’re the closest to Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy, I’ve seen.” I think he meant that as a compliment.

The statement then reviewed at some length the details of my May 1, 1960, flight, concluding: “In connection with Powers’ efforts to operate the destruct switches, it should be noted that the basic weight limitations kept the explosive charge to two and a half pounds and the purpose of the destruct mechanism was to render inoperable the precision camera and other equipment, not to destroy them and the film.”

That was a bit vaguer than I would have liked. Since there was so much criticism on this point, I’d hoped that the agency would make it very clear that even had I activated the switches, the plane itself would not have been totally destroyed.

The statement then concluded that the one hypodermic injection I had been given probably wasn’t truth serum but a general immunization shot; that despite repeated requests to contact the American Embassy or my family, I had been held incommunicado and interrogated for about one hundred days. Paraphrasing me, it observed: “He states that the interrogation was not intense in the sense of physical violence or severe hostile methods, and that in some respects he was able to resist answering specific questions. As an example, his interrogators were interested in the names of people participating in the project, and he states that he tried to anticipate what names would become known and gave those, such as the names of his commanding officer and certain other personnel at his home base in Adana, Turkey, who would probably be known in any case to the Russians. However, they asked him for names of other pilots, and he states that he refused to give these on the grounds that they were his friends and comrades and if he gave their names they would lose their jobs and, therefore, he could not do so. He states they accepted this position. It is his stated belief, therefore, that the information he gave was that which in all probability would be known in any case to his captors.”

Читать дальше