Page 618: “Oswald told him that he had already offered to tell a Soviet official what he had learned as a radar operator in the Marines.”

Page 665: “Oswald stated to Snyder that he had voluntarily told Soviet officials that he would make known to them all information concerning the Marine Corps and his specialty therein, radar operations, as he possessed.”

Page 369: “He stated that he had volunteered to give Soviet officials any information that he had concerning Marine Corps operations, and intimated that he might know something of special interest.”

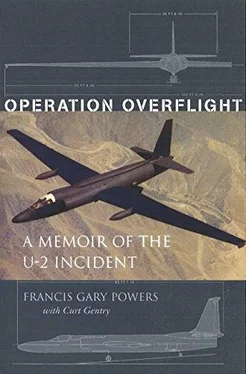

During the six months following the October 31, 1959, embassy meeting, there were only two overflights of the USSR. The one which occurred on April 9, 1960, was uneventful. The one which followed, on May 1, 1960, wasn’t.

Here the trail ends, except for one tantalizing lead, discovered during the research for this volume.

Among the Warren Commission Documents in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., is one numbered 931, dated May 13, 1964, CIA National Security Classification Secret

In response to an inquiry, Mark G. Eckhoff, director, Legislative, Judicial, and Diplomatic Records Division, National Archives, in a letter dated October 13, 1969, stated: “Commission Document 931 is still classified and withheld from research.”

The title of Document No. 931 is “Oswald’s Access to Information About the U-2.”

The former President could write about the U-2 episode; retired agency officials—Dulles, Kirkpatrick—could write about it, as could others in no way connected with the program. The man most directly involved could not.

In August, 1967, I again requested permission to write a book concerning my experiences.

I was more hopeful this time. Raborn had been replaced by Richard Helms, a man who had worked his way up through the ranks of the CIA and undoubtedly knew more about intelligence than any other director since Dulles. There were also indications that intelligence, not politics, was Helms’ primary concern.

I was told that the request would be made of the “big man” at what seemed “the most opportune moment.”

“This isn’t the right time to bring it up,” I was told in a telephone call a couple of weeks later.

Nor was the moment opportune the next time they called. For in the interim the “spy ship” Pueblo had been captured by the North Koreans, and the last thing the government wanted, I was told, was more publicity.

With the seizure of the Pueblo , interest in the U-2 story was reactivated. Although the two events differed in at least one important particular—the Pueblo was outside the territorial waters of North Korea, I had intruded right into the heart of Russia—there were obvious parallels. And some not so obvious, because they involved that portion of the U-2 story which had never been made public. I wondered how many Pueblo episodes would have to occur before we accepted the basic lessons we should have learned from the U-2 crisis.

This was one factor in my decision to go ahead with the book. There were others. My job was not risk-free; if anything happened to me, chances were the story would never be told. Too, and this was not the least of my considerations, in a few years my children would be reading about the U-2 incident in school. I wanted them to know the truth.

In the fall of 1968 I was contacted by John Dodds, editor-in-chief of Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. Dodds was aware of the earlier negotiations for the book, and was anxious to publish my story if I was ready to write it. I was more than ready.

Sue and I flew to New York and talked to him. On our return to California I informed the agency of the Holt offer and, for the last time, asked permission to publish my account.

After waiting several weeks, my patience finally came to an end. Since they had helped perpetuate the Francis Gary Powers mercenary label, I’d play the part. Sarcastically I wrote to them that I was going to write the book, and while entertaining bids, and since they had been so anxious to suppress it, I’d be glad to consider their best offer.

It was, in its own way, my declaration of independence.

To my surprise, I did receive an answer, in the form of a telephone call asking me if I would be willing to come to Washington to discuss the matter. I did, informing them at the outset that I intended to accept the offer made by Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Only then was I told the agency had no objection to my writing the book. While they, of course, couldn’t give such permission in writing, they did want me to know that they would be glad to do anything possible to assist me.

Although not ungrateful for their offer, I politely declined it. Undoubtedly access to their records would shed light on some of the more puzzling aspects of the U-2 episode. On the other hand, such cooperation would carry with it an unspoken obligation. This was to be my version of the story, not the agency’s. I was determined to tell it as I had lived it, and this, to the best of my ability, I have done.

As the writing of the book progressed, I made an interesting discovery. Although this may also sound like sarcasm, it isn’t. In suppressing the book for nearly eight years, the agency did me a favor. I could now tell the story far more fully and frankly than would have been possible in 1962.

I have omitted only a few particulars, and in fairness to the reader I will state their nature.

I have not included the actual altitude of the U-2. By now it may be presumed that Russia, Cuba, and Communist China all know it. Yet, just on the chance that it isn’t known and that the life of a pilot might be placed in jeopardy, it will go unmentioned.

I have not itemized the number of overflights, nor related what intelligence information was received. My reasoning on this matter remains the same as when I first withheld this information from the Russians. Having held it back through many hours of interrogation, I have no intention of giving it to them now for the price of a book.

I have not mentioned certain phases of my training, both in the Air Force and in the agency, which might still be in use and thus beneficial to an enemy.

I have not included the names of other pilots, agency personnel, or representatives of Lockheed and the many other companies involved in the U-2 program. It is not my business to “blow their cover.”

And I have omitted some matters which I feel could affect present national security.

These are the only things excluded.

In the fall of 1969, as the book was nearing completion, I did something else I had wanted to do for a very long time. I wrote a letter.

Dear Zigurd:

It’s been a long time since I last saw you standing in the window at Vladimir as I was being led away. As happy as I was to be leaving, there was a great sadness in me that you were remaining behind those bleak walls.

I’m sure you’ve heard that I was exchanged for Soviet spy Colonel Rudolf Abel. You probably have not heard much of what transpired after my release.

One of the things happening to me now is that I am writing my life story, to be published in the spring of next year. The research and reviewing of my journal and diary brought back memories, many of which I have tried to forget.

I am sending this letter to you in care of your parents, at the address you gave me the night before I left Vladimir. If you are allowed to correspond, I would like very much to hear from you. If the above-mentioned proves to be a good address, I will send you a copy of my book as soon as it is published. It will bring you up to date on the many things that have happened since I last saw you.

I hope your parents are well and happy. It would please me if you would convey to them my best wishes and my sincerest appreciation for the aid and kindness they showed me while we were at Vladimir.

Читать дальше