I’m not too sure the loss was all that great.

As a people, we Americans grew up a little in May, 1960, and during the days that followed. As with any growing process, it was at times a painful experience.

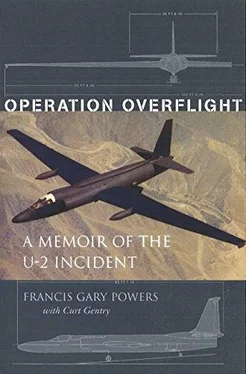

Yet I suspect that, for more than a few persons, reaction to the disclosure that we were keeping our eyes on Russia must have been similar to what I first felt in 1956 on learning of Operation Overflight; pride that the United States could conceive and carry out an intelligence operation of such boldness and importance; relief that we weren’t asleep, weren’t totally unprepared.

I’m also inclined to agree with Philip M. Wagner, when he wrote in the June, 1962, Harper’s that President Eisenhower’s admission that the United States was engaged in espionage “had a number of wholesome effects.”

“For one thing, it invoked a sudden respect for American intelligence work which had not been general in Europe. In invoked that same respect in Russia. It also caused abrupt revision of estimates of American military strength, and such estimates are important influences on the course of diplomacy. If we had been able to keep that secret, what other secrets were we perhaps keeping? Were we as weak as many had been saying? Possibly not. It caused other revisions of judgment. U-2 was damning commentary on the supposed invulnerability of Russian air defense.”

Also, I’m not too sure some of those negative aspects mightn’t prove to be of positive value. It isn’t necessarily bad that we’ve become suspicious of the motives behind some of our governmental pronouncements, that we question whether certain information is being withheld from the public because of “national security” or for strictly political reasons, that our elected leaders are on occasion called upon to justify their actions to the people they represent, that we demand—though we don’t always obtain—a greater honesty from our officials.

The alternative is the kind of government to be found in the Soviet Union, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Communist China, and elsewhere.

Following the U-2 incident, espionage attained an acceptance in the United States reaching the dimensions of a popular fad. Beginning with America’s discovery of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels and the popularity of such TV shows as I Spy it progressed to the much more realistic novels of John LeCarré and others.

In 1960, in the earliest cover stories following the downing of the U-2, the United States denied its engagement in anything so distasteful as espionage.

In 1968, with the capture of the Pueblo, the United States was frank from the outset in admitting that the ship’s mission was intelligence-gathering.

In my trial in August, 1960, when, acting on the advice of counsel, I stated that I was “deeply repentant and profoundly sorry,” many in the U.S. damned me for doing so.

In December, 1968, when a representative of the United States government signed a document admitting that the Pueblo had invaded North Korean waters, at the same time stating that this was a lie, done only to effect the release of the crew, there was little criticism of his action.

For better or worse, we’ve grown up to accept some of the realities of our times, unpleasant though they may be.

But then, we’re not the only ones who’ve done so. In 1960 the Soviet Union was still denying that it used spies. In 1962 the release of Powers and Abel was not an exchange, for Abel was not one of theirs; it was simply a gesture of Soviet humaneness, on behalf of the families of the two men (which, presumably out of modesty, they did not bother to announce in the USSR). It was therefore with more than a little amusement that I read a wire-service report in November, 1969, describing an event in East Berlin. One of that city’s streets was being renamed for Richard Sorge, the remarkable agent who stole German and Japanese secrets for the Russians. Present for the dedication ceremony, according to the account from behind the Iron Curtain, were Russia’s most famous spies, including one Rudolf Abel.

In 1970 the U-2 will celebrate its fifteenth birthday. Those few which remain, that is.

Of the original aircraft, less than one-third survive. None died of old age. None were junked for parts. All met violent ends. Communist China accounted for at least four, Cuba two, Russia one. Communist China has released a photograph of four it downed. The actual number may be higher. These particular planes are owned and piloted by Nationalist China. In addition to the crash which killed Major Anderson, another went down while returning from a Cuban overflight.

Ironically, the aircraft which made so many headlines during the sixties was never produced during that decade. Production ceased in the late fifties.

It’s no secret that the U-2, manned by USAF pilots, again proved its value over Vietnam. Elsewhere, its primary use today is for high-altitude air sampling to detect and measure radio-activity. Not too long ago the U-2 also played a major role in a program to obtain data on high-level turbulence, to determine its effect on supersonic transports.

Some have the impression that the U-2 became obsolete with the advent of the space satellite, just as the covert agent was supposedly superseded by the spy flight. Neither example is true, and I believe it is dangerous if we deceive ourselves into thinking this is so. Each had, and continues to have, its uses and can obtain information which the other can’t. As far as I know, a satellite can’t fly over a country at any time of the day or night and photograph exactly what it chooses. Nor can it fly slow enough to monitor radio and radar messages in their entirety. Too, for all the claims made by both Russia and the United States, I’ve still to see any photographic evidence that its cameras can pick out troops in the field or even smaller objects. Someday maybe. But at present I remain unconvinced.

Yet the fact remains that as an aircraft the U-2 is a vanishing species.

When I began working at Lockheed I had about six hundred hours’ flight time in the U-2. Today I have in excess of two thousand. I know and respect the plane, and would like to see its life extended. Of a number of possible uses which have occurred to me, two may merit mention. One is the possibility that NASA, or possibly one of the larger universities, obtain one of the Air Force U-2s and adapt it for installation of a telescope for use in astronomy. Since it flies above ninety percent of the earth’s atmosphere, the photographs would be exceptionally clear. The other possibility would be for a TV network to purchase several for transmission of weather pictures. Thus, before leaving for work in the morning, the viewer could not only see the weather picture over the area where he lived and worked, he could also follow the course of storm fronts as they moved in and know what was coming up. Only someone who has flown in a U-2 can realize how graphic such an overview can be.

There are, I’m sure, other possibilities such as map making, particularly of heretofore uncharted areas. And in wanting to prolong the usefulness of the U-2, my motives, I must admit, are not entirely unselfish. For the year 1970 will probably mark the end of my association with the U-2. In October, 1969, as this book was in its final stages, I was informed by “Kelly” Johnson that, U-2 test work being scarce, as of early 1970 my services would no longer be required at Lockheed.

As I write this, it’s possible I’ve already made my last U-2 flight.

Regrets? Yes, I have a few. My greatest is not that I made the flight on May 1, 1960; rather the opposite—that we did not do more when we had the chance. We had the opportunity, the pilots, the planes, and, I sincerely believe, the need. Yet from the very start of the program in 1956 we made far fewer overflights of Russia than were possible. Moreover, from early 1958 until April, 1960, we made almost none. If the program was important to our survival in 1956 and 1957—and I’m convinced it was because of the single flight which exposed the Russian bomber hoax and alerted us to the USSR’s emphasis on missiles, then in itself it alone was worth the cost of the whole program, saving not only millions of dollars but, possibly, millions of lives. The overflights became even more important as Russia’s missile development progressed. We could have done much more than we did. I regret that we did not. I only hope that time won’t prove this to have been one of our costliest mistakes.

Читать дальше