That first night on the back deck of the ship, I had told Lyuba that I never had a desire for a child. Physically, pregnancy had never appealed to me but I missed the chance for a family. I was living another life, a life I have not regretted. “Is it a form of protest?” the Russian woman had asked. Did that mean I was trying to challenge traditions, living on the edge? Now, so used to my life as a lesbian, I couldn’t trade it.

I was so drawn to Lyuba and enjoyed our lovemaking. The festival had been such hard work, and when it was almost over all kinds of emotions, feelings of love and gratitude and frustration got entwined with the passion. My intense feelings led to a yearning for intimacy. And Lyuba was there. I didn’t think at the time that it may not be right. I wanted to be touched, to be close. It was an expansive feeling of love in the context of the festival.

What happened in Moscow? It was terrible. A change of heart or a change in context. Perhaps an excuse to sever the relationship, on my part, and maybe on hers too. Sabotage.

I often went to my close friends’ dacha when I was in Moscow. It was in Pobeda, about an hour by train from the Kiev station, not far from where Sophia Parnok spent her last days. My friends, Lena and Sveta, like Alice and Gertrude, had been a couple for over twenty years and many queer friends came to their dacha and visited. When I arrived one evening, tired and hot from the elektrichka ride and standing most of the way, Sveta met me at the door. I hugged her and she said in a low voice: “Lyuba is here. The one from Tomsk.”

I was shocked. “How did she get here?”

“I don’t know. She called Lena and I think she wanted to come here because of you, and so they came out together earlier today.” I remembered I had left her Lena’s number once as a way to contact me if she needed to.

I walked into the dining room and Lyuba acted as if she had always been there, always known my friends at the dacha. She was engaged in some conversation with Vitya and didn’t come right over to greet me. I could tell immediately she had been drinking. Then I saw a bottle of vodka in the middle of the table. The whole situation upset me—she was coming into my territory, my friends, on her own. It was odd the way she set up these connections independently, because of me, or to get to me? She rose and angled over to me, giving me a cursory hug. I hugged and greeted Vitya and Lena. I didn’t know what was going to happen, but I didn’t want her there in that condition blabbing about who knows what.

The evening was difficult. I had had issues with alcoholics, and I feared she was joining the crowd. We had let go of each other by mail, ending the affair, but I felt she was coming after me obliquely. Moscow was a very long way from Tomsk. Why was she here? And why did she seek out my friends?

We slept in separate beds. The next day we left together. I found myself furious with her for drinking and seeking me out. We argued on the elektrichka while everyone else in the train sat like statues. She claimed she just wanted to meet my friends—who weren’t mine alone. I said I could barely talk to her last night and that she still reeked of alcohol. The argument was irreparable. We didn’t contact each other again.

And then a letter came, trying to rekindle something. I couldn’t. So much had worn down the love. My life had changed in the U.S. It was no use. The memory of making love during white nights in St. Petersburg that time we were there remains. “And pink flamingos flew into Tomsk after the festival, did you know that,” she had said before things got sour. What a phenomenon! Weren’t they supposed to migrate to Africa? Yet they flew to Siberia.

I will never forget when Lyuba first put her arms around me on that cool, moonlit night on the deck and we kissed so deeply. The rest did not matter—the details, I mean. Back home, I simply felt less lonely for a while. Someone cared about me on the other side of the world. I loved wearing her ring. It was big and beautiful like she was. Halfway around the world someone was thinking about me. When the moon was full above the hill, I wondered if she could see the same moon even though it was midday in Tomsk. She had looked at it fifteen hours earlier, perhaps.

Was it the same?

If I am making a difficult decision or feeling in a funk, I go to a place in my mind that brings together key people and aspects of my life. I visualize a vast open field where horses graze, a green field with an area sheltered by craggy oak trees. I sit with my imaginary wise old friend/mentor, a tall and strong woman with flowing gray hair. My cat steps toward us in his stealthy way; friends from long ago and now, acquaintances I care about, my sister who died at eighteen, a friend I met in San Francisco, those who nurture and have nurtured me, and others I have met all draw near. The air is fresh and easy, the sun ablaze. The creek beside us gurgles and nature embraces us. This is how I imagine the natural alliance between gender and queer theory—a field of shared knowledge and interdisciplinary work.

An important milestone in my life was interviewing close to a hundred queers, sexual minorities, in Russia in the 1990s. I had many rich meetings with people, and their openness, their willingness to explain themselves to me, was humbling. I even helped make connections between Russian and U.S. transgender people. An extensive interview with a man who had spent a total of eighteen years in prison in Siberia for being gay was especially revealing. He was a gentle, animated person, a rich storyteller in Russian, with the expressiveness of a true performer. In his late fifties, his white hair curling at the ends and a broad smile showing a gold tooth, he related the story of his first adolescent love affair with another boy as if it had just happened. His time in prison and other details he chose to relate captured a life that few people have known.

“What would I want?” he said when I asked at the end of the interview if there was anything he’d like to add. He sighed and smiled, ”To live freely, to be able to get together openly in a club. I want to live and relax among my own kind, our people—to talk, to sit in a cafe, not in some closet. That’s what I want, just one thing, an open society.” A dream of community, a desire to be among his own kind, and an open society!

People want to be accepted for who they are, but we live in a world in which we can be easily stereotyped or even put in prison, brutalized, or killed for who we are. In the U.S., we had the vicious cases of a young gay man, Matthew Shepard, beaten to death in Wyoming, and Brandon Teena, who was raped and killed in Nebraska for being transgender (as depicted in the film, Boys Don’t Cry ). Young people are bullied in the schools everywhere, which sometimes drives them to suicide—and being gay, lesbian, or a boy who seems girlish are by far the greatest bullying points in schools.

“In a 2005 survey about gay bullying statistics, teens reported that the number two reason they are bullied is because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender expression. The number one reason reported was because of appearance. In fact, about 9 out of 10 LGBT teens have reported being bullied at school within the past year because of their sexual orientation,” according to the website bullyingstatistics.org.

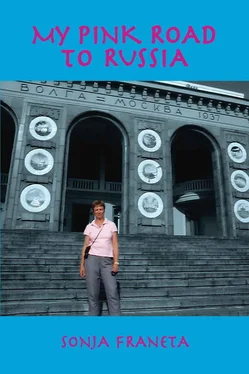

In September of 1996, I helped bring a queer film festival to Tomsk, Siberia. One of the films was by Yugoslav director Zelimir Zilnik, Marble Ass . It takes place in Serbia (part of the former Yugoslavia) during the beginning of the nationalist war there. The main characters in the film are a gun-wielding macho man who has just returned from battle, hungry for more killing, and two transgender (male-to-female) prostitutes for whom killing is the furthest thing from their minds. The film depicts a feminine view of war through the eyes of transgender women who have refused to be men. The prostitutes’ words, their relationship, their gentleness, and their refusal to participate in the violence all around them is touching and profound. Especially significant is the fact that the film came from an extremely misogynistic society in which the the government was promoting war against ethnic groups, and against women as a gender. The transgender women are important symbols.

Читать дальше