Warmest best regards ALL ROUND.

Your Mu

13. To Erich Lichtenstein

Berlin, 22 January 1925

Dear Dr. Lichtenstein,1

I am writing to you on the instructions of Dr. Max Krell.2 I seem to recall writing to you once before. By mid-February I shall have completed a novel. However, I am contractually tied to the “Schmiede.”3 I will admit to you quite openly, though with a plea for discretion, that I am not satisfied with either the promotion, the payment, or the appearance of the books. Nor do I think the Schmiede will be overjoyed to learn of my new terms. So it might very well come about that you and I will have business with one another.

At the same time, I would like to write books other than novels, books that are not covered by my contract with the Schmiede. For instance, I have long toyed with a plan to write a book of cheeky and irreverent dialogs on (in the broadest sense) “questions of the day.” I can imagine the book appearing under the title “Alfred and Edward,” or something of the sort.

I am told you are sometimes to be found in Berlin. I will be here until March, and thereafter in Paris. If you are ever in the city, I should like to be informed. In any case, I should be grateful for the kindness of an acknowledgment.

Yours sincerely,

Joseph Roth

N 35, Potsdamerstrasse 115 a. c/o Tome

1. Lichtenstein: Dr. Erich Lichtenstein (1888–1967), reviewer, publicist, and publisher. This letter is an early instance of Roth’s simoniac tendencies as an author, his self-given right to agitate, to inveigh, to two-time, and ultimately to desert publishers. (NB, such behavior on his part comfortably antedated exile and Third Reich.)

2. Max Krell worked as an editor for another publisher, the Propyläen Verlag.

3. The unfortunate “Schmiede” was where Roth’s books for a time appeared. Roth’s swagger is hard to take, and hard to like.

PART III. 1925–1933: Paris, Points South and East, Disappointment, Tragedy, and Triumph

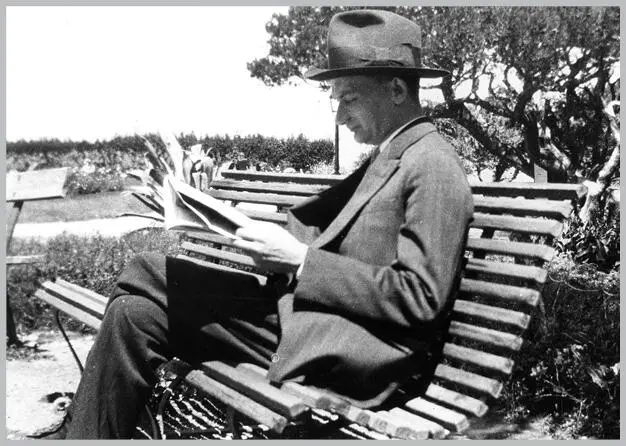

JOSEPH ROTH WITH THE TRADEMARK NEWSPAPER

France — the Midi, Paris, Marseille — marks nothing less than the appearance of grace in Roth’s life. (And for once, not — his phrase — the “grace of unhappiness.”) Something unlooked for, undreamed of, or perhaps only dreamed of, something exceeding any human measure of reason or cognition. It is one of those classic collisions between the highly intelligent and almost post-mature but somehow starved observer and the Abundant Place: other instances that come to mind involve poets: Osip Mandelstam in Georgia, and Elizabeth Bishop in Brazil. Roth for once flaps at the limits of sense — which, as witness the reproving letters to his friend and protégé Bernard von Brentano (or later to Stefan Zweig), is something he hates to do, he disdains anything incoherent, stuttering, pompous, blathering. “I feel driven to inform you personally that Paris is the capital of the world, and that you must come here,” he writes in no. 14 to his boss-cum-friend Benno Reifenberg, “Paris is Catholic in the most urbane sense of the word, but it’s also a European expression of universal Judaism.” (Reifenberg got it, and later got to be the paper’s Paris correspondent himself.) Roth’s delirium, cooled and formed, is still palpable in the beautiful series of pieces he gave the Frankfurter Zeitung (they ran between 8 September and 4 November 1925), called Im mittäglichen Frankreich , “In the French Midi,” and a projected — and sadly, rejected — book version to be called “The White Cities.” I found the white cities just as they were in my dreams,” he writes in the title piece, ending with a landscape of Matisse-like strength, serenity, and loveliness:

The sun is young and strong, the sky is lofty and deep blue, the trees dark green, ancient, and pensive. And broad white roads that have been drinking in and reflecting the sun for hundreds of years, lead to the white cities with flat roofs, which are as they are to prove that even elevation can be harmless and benign, and that you never, ever fall into the black depths.

In a life full of calamities — his father’s madness before he was even born, Friedl’s schizophrenia, the end of the Dual Monarchy, Hitler’s coming to power — the loss of the Paris correspondent’s job for the Frankfurter Zeitung seems perhaps the most gratuitously wounding of all. It is too tantalizing to imagine Roth’s life with — in the full, officially possessing sense of the word — Paris. Perhaps his critical, oppositional spirit would have asserted itself sooner or later anyway; the novelist would have shouldered his way out past the journalist. But as it was, the Frankfurter gave, and the Frankfurter took away: for Roth, the flat roofs of the white cities were to have hurtful and malign black depths below them after all. In its unwisdom (and in the financial and organizational and political nervousness and turmoil of the twenties), this Jewish-liberal institution made the Nationalist — and later Nazi — Friedrich Sieburg its Paris correspondent, reasoning that Sieburg could do reporting as well as feuilleton. Roth in 1934 made a sour little joke about Sieburg’s busily seeking God in France (it’s an expression meaning something like “high on the hog”), while the Germans had happily found Wotan at home in Germany — but his feelings toward the man were not amusing or benign. Roth — hardly nature’s idea of a docile employee anyway — never subsequently trusted the paper, but then you could argue that he had probably never previously trusted it either. In any case, who could blame him? He remained based in Paris, half out of protest, but demoted, casualized, cantankerous, and impatient to be done with newspapers.

The antagonistic relationship between the FZ and its star writer is one of the burdens of this correspondence. Lines of command at the paper were, to say the least, fuzzy. There was an editorial committee — hence the extraordinary proliferation of newspapermen’s names in some of these letters (a history of Th e New Yorker would be no different, of course). Design, personnel, allegiances, politics, finance, all underwent continual change. Hence one’s sense of Roth’s at times loitering unhappily and unproductively around the head office in Frankfurt — he was watching his own back. Hence, too, his adoption of the slightly younger Brentano — it was so that he too might have someone to command, to patronize, to induct into mysteries, and to lead into battle. From these letters, one feels that there was any number of chiefs at the Frankfurter , and Roth their only Indian. It was a remarkable paper, distinguished, even unrivaled, in its roster of writers, among them Walter Benjamin — but it also had a powerful (and to Roth, never that much of a team player, rather nauseating) sense of its own distinguished remarkability. Newly arrived in Paris, or in Russia, out of sight of it, he still had some interest in its affairs, and wrote painstaking critiques and — practically! — memos to senior colleagues. A few years later, he had none. In 1931, he wrote to Friedrich Traugott Gubler, Reifenberg’s successor as feuilleton editor, “It’s just a paper, only slightly better than the others in Germany. It’s no longer absolutely good or essential. And neither you nor Reifenberg nor Picard will be able to fix it. You will sacrifice your personal lives, the only important thing.” And this is what he then, rather movingly, goes on to prescribe: “Always do what your wife says, spend time with her and the children, discuss everything with her, and don’t do anything just because your obstinate man’s head tells you to.” The Frankfurter ’s sense of exceptionalism — one might almost call it “manifest destiny”—mixed, of course, with relativism, kept it going, trimming as it went, through ten years of the Third Reich, until it was finally closed down in August 1943. Like some of his colleagues, Reifenberg, who stayed at the paper throughout, and was involved in its next incarnation as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of today, was persuaded that they had managed to keep up some coded, clandestine resistance to the Nazis in their columns. Looking at some contributions with a view to putting together an anthology of them in the 1950s, he was forced to realize there was no resistance in any meaningful sense, not that any reader would have understood. The newspaper was trapped in a vainglorious bubble of its own making; and Roth, who after 1933 would have nothing to do with it, and broke off all relations with colleagues still there, was tacitly and belatedly vindicated in his intransigence.

Читать дальше