Dedication

To Philip and Lynn Asquith for their support,

and to my grandparents Stella and Frank Ford

Epigraph

Whoever loves much, does much. Whoever does a thing well does much. And he does well who serves the common community before his own interests.

—Thomas à Kempis

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

Note on Text

List of Maps

Part I

Chapter 1: Invasion

Chapter 2: Occupation

Chapter 3: Arrival

Chapter 4: Survivors

Chapter 5: Resistance

Chapter 6: Bomber Command

Part II

Chapter 7: Radio

Chapter 8: Experiments

Chapter 9: Shifts

Chapter 10: Paradise

Chapter 11: Napoleon

Part III

Chapter 12: Deadline

Chapter 13: Paperwork

Chapter 14: Fever

Chapter 15: Declaration

Chapter 16: Breakdown

Part IV

Chapter 17: Impact

Chapter 18: Flight

Chapter 19: Alone

Chapter 20: Uprising

Chapter 21: Return

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Characters

Select Bibliography

Notes

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

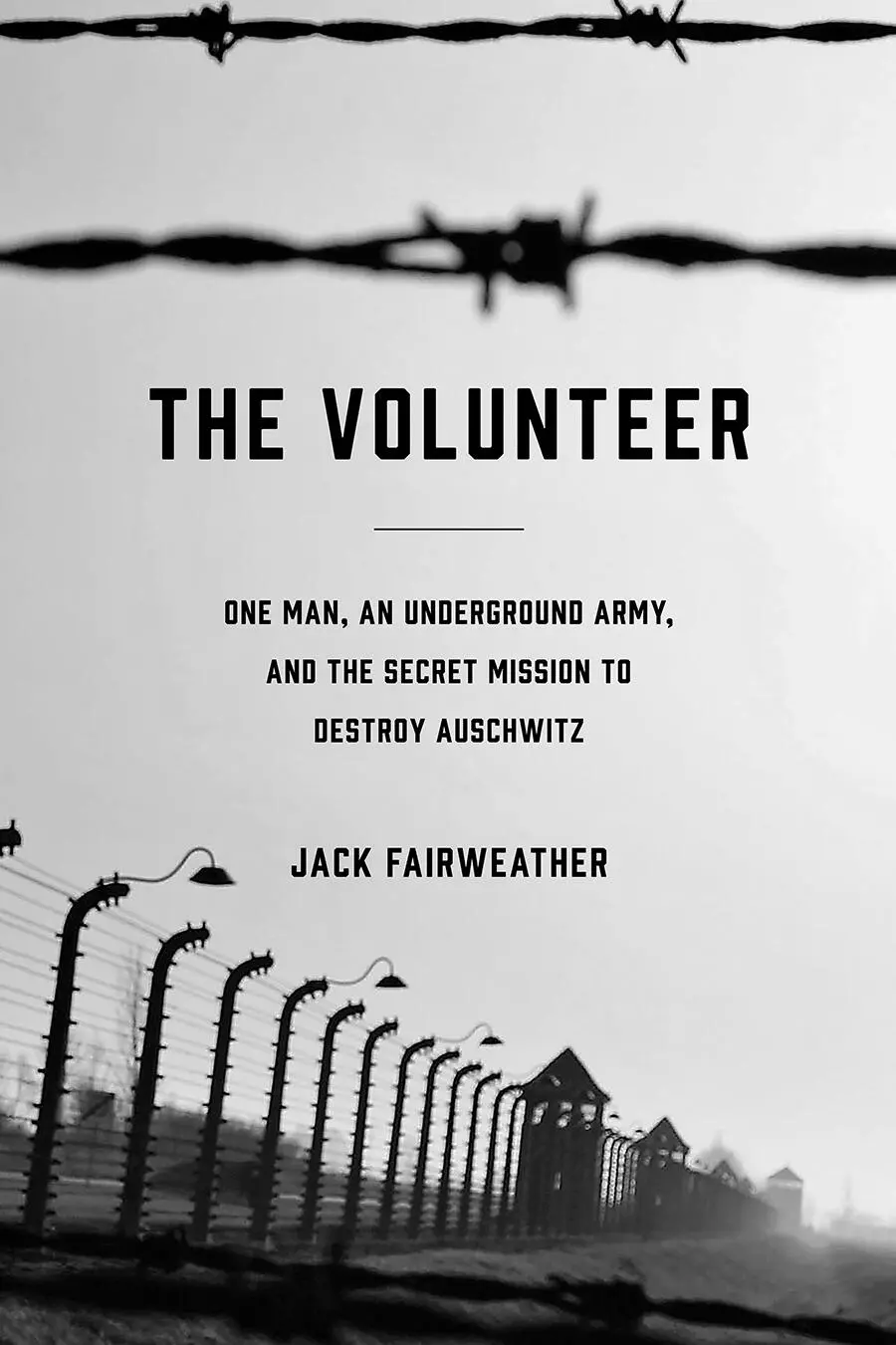

Witold Pilecki volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz . This barest outline of a story sent me on a five-year quest to retrace his footsteps from gentleman farmer to cavalry officer facing the Blitzkrieg to underground operative in Warsaw and then human chattel in a camp-bound cattle car. I’ve come to know Witold well. Yet I find myself returning to that simple sentence and the moment he sat waiting for the Germans to burst into his apartment as I reflect on what his story promises to tell us of our own time.

I first heard about Witold’s story from my friend Matt McAllester at a dinner in Long Island in the fall of 2011. Matt and I had reported together on the wars in the Middle East, and were struggling to make sense of what we’d witnessed. In typically bravura fashion Matt had traveled to Auschwitz to confront history’s greatest evil and learned of Witold’s band of resistance fighters inside the camp. The idea of a few souls standing up to the Nazis comforted us both that night. But I was equally struck by how little was known about Witold’s mission to warn the West of the Nazis’ crimes and create an underground army to destroy the camp.

Some of the pictures were filled in a year later when Witold’s longest report about the camp was translated into English. The story of the report’s emergence was remarkable in itself. A Polish historian named Józef Garliński gained access to the document in the 1960s, only to discover that Witold had written all the names in code. Garliński managed to decipher large portions of it through guesswork and interviews with survivors to publish the first history of the resistance movement inside the camp. Then in 1991, Adam Cyra, a scholar at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, discovered Witold’s unpublished memoir, a second report, and other fragmentary writings that had been locked away in Poland’s archives since 1948. This material came with Witold’s key to identifying his coconspirators.

The report I read in 2012 showed Witold to be an exacting chronicler of his experience in Auschwitz who wrote in raw and urgent prose. But it was only a fragmentary and sometimes distorted account. He didn’t record critical episodes for fear of exposing his colleagues to arrest, hid devastating observations, and carefully framed events to suit his military audience. Many questions remained, none more critical and elusive than this: What became of the intelligence he risked his life to gather in Auschwitz? Did he provide the British and Americans with information about the Holocaust long before they publicly recognized the camp’s role? Was his reporting suppressed? How many lives could have been saved had his warnings been heeded?

Students of the Holocaust quickly learn that it is a story not only of millions of innocent Europeans being murdered but of a collective failure to recognize and act on its horror. Allied officials struggled to discern the truth, and when confronted with the reality they stopped short of the moral leap necessary for action. But this wasn’t only a political failure. The prisoners of Auschwitz also struggled to imagine the scope of the Holocaust as the Germans transformed the camp from a brutal prison to a death factory. They too succumbed to the human impulse to ignore or rationalize or dismiss the mass murders as separate from their own struggle. Yet Witold did not. Instead he staked his life on bringing the camp’s horror to light.

I have tried in this book to understand what qualities set him apart. But as I uncovered more of his writings and met those who knew him and, in a few cases, fought beside him, I realized that perhaps the most remarkable fact about Witold Pilecki—this farmer and father of two in his late thirties with no great record of service or piety—is that he was not so different from you and me. This recognition brought a new question into focus: How did this average man expand his moral capacity to piece together, name, and act on the Nazis’ greatest crimes when others looked away?

I offer his story here as a provocative new chapter in the history of the mass murder of the Jews and as an account of why someone might risk everything to help his fellow man.

Charlotte, 2019

Note on Text

This is a work of nonfiction. Each quotation and detail has been taken from a primary source, testimony, memoir, or interview. The majority of the two-thousand-plus primary sources this book is based on are in Polish and German. All translations were carried out by my brilliant researchers, Marta Goljan, Katarzyna Chiżyńska, Luiza Walczuk, and Ingrid Pufahl, unless otherwise stated.

There are two established sources for understanding Witold’s life in the camp: the report he compiled in Warsaw between October 1943 and June 1944, and a memoir written in Italy in the summer and fall of 1945. 1Remarkably few mistakes crept into his accounts given the circumstances under which he wrote, on the run and without access to notes. But Witold is not a perfect narrator. Wherever possible I have tried to corroborate his writings, correct errors, and fill in the blanks. The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum has 3,727 prisoner accounts, including two dozen that describe Witold’s activities and hundreds more recording events he witnessed. Other archives with important details and context include Archiwum Akt Nowych, Archiwum Narodowe w Krakowie, Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, the Ossolineum, the British Library, the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, the Polish Underground Movement Study Trust, the Chronicle of Terror Archives at the Witold Pilecki Institute, the National Archives in Kew, the Wiener Library, the Imperial War Museum, the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the FDR Presidential Library, the Hoover Institution, the Yad Vashem Archives, the Central Zionist Archives, the German Federal Archives in Koblenz and Berlin, the Swiss Federal Archives, the Archivum Helveto-Polonicum Foundation, and the International Committee of the Red Cross Archives.

Over the course of research, I have also had access to the Pilecki family papers, and unearthed letters and memoirs kept by the families of his close collaborators that shed light on his decisions. Incredibly, several of those whom Witold fought alongside were alive when I began research and offered their reflections. 2

Читать дальше