I have been guided in writing by Witold’s own rule for describing the camp: “Nothing should be ‘overdone’; even the smallest fib would profane the memory of those fine people who lost their lives there.” It has not always been possible to find multiple sources for some scenes, which is reflected in the endnotes. At other times, I have included camp details that it’s clear Witold would have witnessed but does not mention in his reports. I cite sources in the endnotes in the order in which they appear in each paragraph. When quoting conversations, I note the source of each speaker once. In the case of conflicting accounts, I have given Witold’s writings primacy unless otherwise stated.

Polish names are wonderful and sometimes daunting for an English speaker to read. I have used first names or diminutives for Witold and his inner circle, which also reflects how they spoke to one another. I have also tried to cut down on the use of acronyms, and hence refer, for example, to the main resistance group in Warsaw as the underground. For place-names I have retained prewar usage. I use the name Oświęcim for the town, and Auschwitz for the camp.

List of Maps

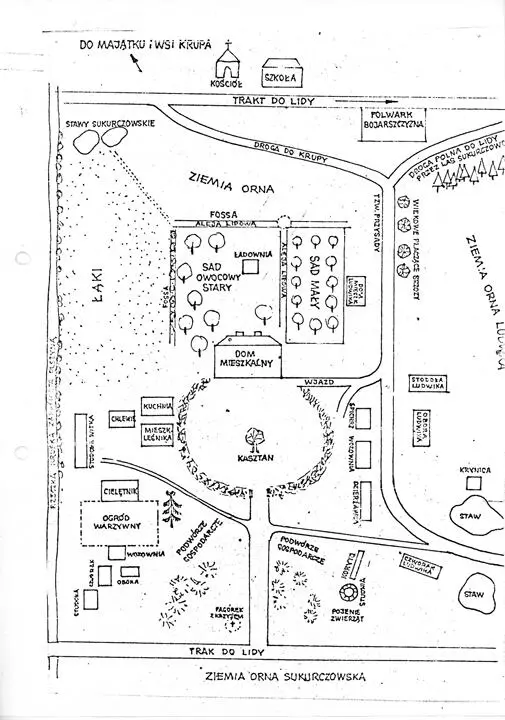

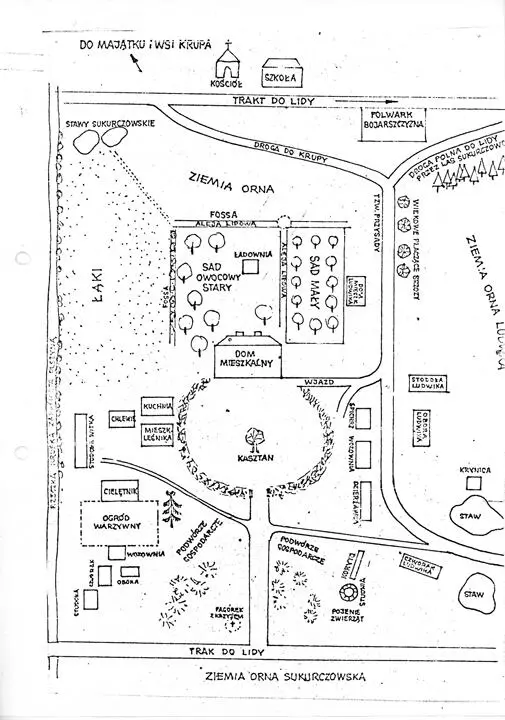

Map 1—Sukurcze

Map 2—Poland, 1939

Map 3—Warsaw, 1939

Map 4—Auschwitz Concentration Camp, 1940

Map 5—Bombing Request Report, 1940

Map 6—Camp Connections, 1941

Map 7—Main Camp Expansion, 1941

Map 8—Birkenau Expansion, 1941

Map 9—Soviet Gassing Reports, 1941

Map 10—Camp Connections, 1942

Map 11—Stefan and Wincenty’s Escape, 1942

Map 12—Jaster’s Escape, 1942

Map 13—Napoleon’s Route, 1942–3

Map 14—Bakery

Map 15—Witold’s Escape, 1943

Map 16—Warsaw, August 5, 1944

I

Chapter 1

Invasion

KRUPA, EASTERN POLAND

AUGUST 26, 1939

Witold stood on the manor house steps and watched the car kick up a trail of dust as it drove down the lime tree avenue toward the yard and came to a stop in a white cloud beside the gnarled chestnut. The summer had been so dry that the peasants talked about pouring water on the grave of a drowned man, or harnessing a maiden to the plow to make it rain—such were the customs of the Kresy, Poland’s eastern borderlands. A vast electrical storm had finally come only to flatten what was left of the harvest and lift the storks’ nests off their posts. But that August Witold wasn’t worrying about grain for the winter. 1

The radio waves crackled with news of German troops massing on the border and Adolf Hitler’s threat to reclaim territory ceded to Poland at the end of World War I. Hitler believed the German people were locked in a brutal contest for resources with other races. It was only by the “annihilation of Poland and its vital forces,” he had told officers at his mountain retreat in Obersalzburg on August 22, that the German race could expand. The next day Hitler signed a secret nonaggression pact with Josef Stalin that granted Eastern Europe to the Soviet Union and most of Poland to Germany. If the Germans succeeded in their plans, Witold’s home and his land would be taken and Poland reduced to a vassal state or destroyed entirely. 2

A soldier stepped out of the dusty car with orders for Witold to gather his men. Poland had ordered a mass mobilization of half a million reservists. Witold, a second lieutenant in the cavalry reserves and member of the local gentry, had forty-eight hours to deliver his unit to the barracks in the nearby town of Lida for loading onto troop transports bound west. He had done his best to train ninety volunteers through the summer, but most of his men were peasants who had never seen action or fired a gun in anger. Several didn’t own horses and planned to fight the Germans on bicycle. At least Witold had been able to arm them with Lebel 8 mm bolt-action carbines. 3

Witold hurried into his uniform and riding boots and grabbed his Vis handgun from a pail in the old smoke room, where he’d hidden it after catching his eight-year-old son, Andrzej, waving it at his little sister earlier in the summer. His wife, Maria, had taken the children to visit her mother near Warsaw. He’d need to summon them home. They’d be safer in the east away from Hitler’s line of attack. 4

Witold heard the stable boy readying his favorite horse, Bajka, in the yard and took a moment to adjust his khaki uniform in one of the mirrors that hung in the hallway beside the faded prints depicting the glorious but doomed uprisings his ancestors had fought in. He was thirty-eight years old, of medium build and handsome in an understated way, with pale blue eyes, dark blond hair brushed back from his high forehead, and a set to his lips that gave him a constant half smile. Noting his reserve and capacity to listen, people sometimes mistook him for a priest or a well-meaning bureaucrat. He could be warm and effusive, but more often gave the impression of holding something back. He held exacting standards for himself and could be demanding of others, but he never pushed too far. He trusted people, and his quiet confidence inspired others to place their trust in him. 5

Map of Sukurcze from Witold’s sister’s memoir.

Courtesy of PMA-B.

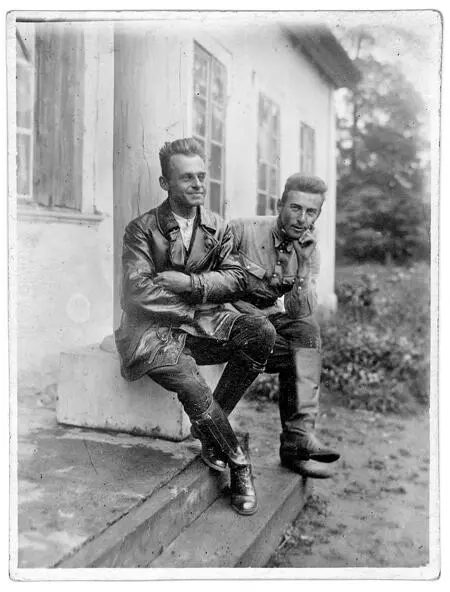

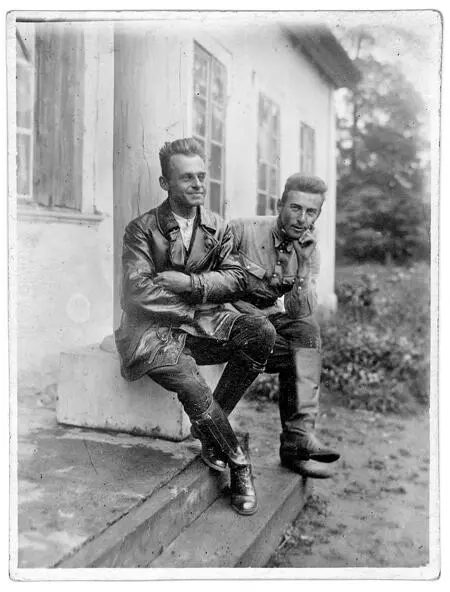

Witold Pilecki and a friend in Sukurcze, c. 1930.

Courtesy of the Pilecki family.

As a young man he’d wanted to be an artist and had studied painting at university in the city of Wilno, only to abandon his schooling in the tumultuous years after World War I. Poland declared independence in 1918 out of the wreckage of the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires but was almost immediately invaded by Soviet Russia. Witold skirmished against the Bolsheviks with his scout troop and fought on the streets of Wilno. In the heady days that followed victory, Witold didn’t feel like picking up his paintbrushes. He clerked for a while at a military supply depot and a farmers’ union. Then in 1924 his father fell ill and he was honor bound to take on his family’s dilapidated estate, Sukurcze, with its crumbling manor house, overgrown orchards, and 550 acres of rolling wheat fields. 6

Suddenly, Witold found himself the steward of the local community. Peasants from the local village of Krupa worked his fields and sought his advice on how to develop their own land. He set up a dairy cooperative to earn them better prices, and, after spending a large chunk of his inheritance on his prized Arabian mare, founded the local reserve unit. He met his wife, Maria, in 1927 while painting scenery for a play in Krupa’s new schoolhouse and courted her with bunches of lilac flowers delivered through her bedroom window. They married in 1931, and within a year their son, Andrzej, was born, followed twelve months later by Zofia, their daughter. Fatherhood brought out Witold’s caring side. He tended to the children when Maria was bedridden after Zofia’s birth and taught them to ride and to swim in the pond beside the house. In the evenings, they staged little plays for Maria when she came home from work. 7

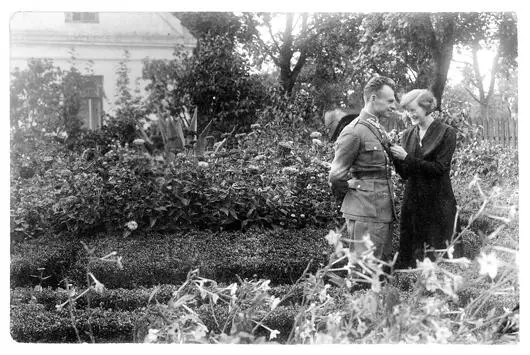

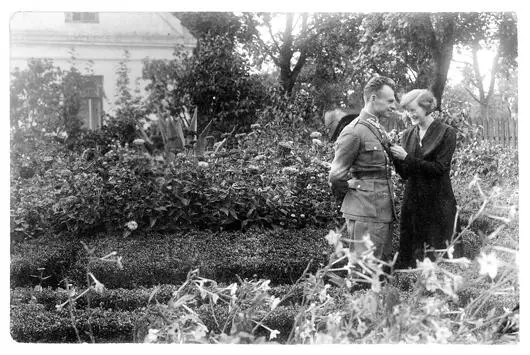

Witold and Maria shortly after their wedding, c. 1931.

Courtesy of the Pilecki family.

But his quiet home life was not cut off from the political currents sweeping the country in the 1930s, and Witold worried. Poland had been one of the most pluralistic and tolerant societies in Europe for much of its thousand-year history. However, the country that had reemerged in 1918 after 123 years of partition had struggled to forge an identity. Nationalists and church leaders called for an increasingly narrow definition of Polishness based on ethnicity and Catholicism. Groups advocating greater rights for Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities were broken up and suppressed, while Jews—who comprised around a tenth of Poland’s prewar population—were labeled economic competitors, discriminated against in education and business, and pressured to emigrate. Some nationalists took matters into their own hands, enforced boycotts of Jewish shops, and attacked synagogues. Thugs in Witold’s hometown, Lida, had smashed up a Jewish confectionary and a lawyer’s office. The main square was filled with shuttered shops belonging to Jews who had fled the country. 8

Читать дальше