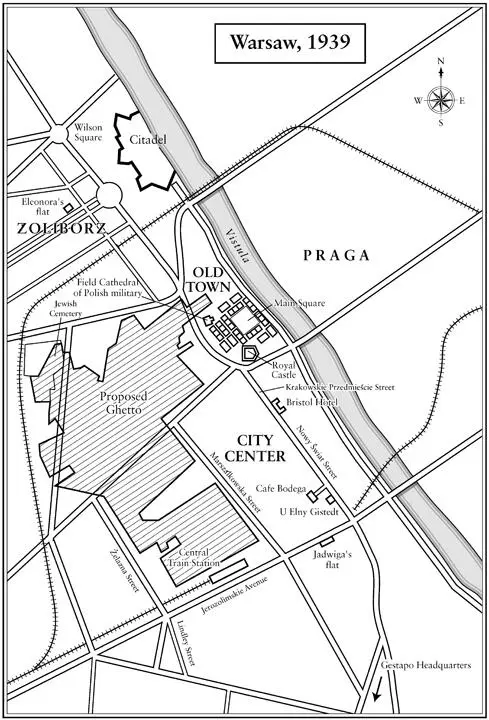

The Germans in this rubric were the master race, along with any Poles who could prove German ancestry and agreed to sign a special “Volksliste” registry. They were given jobs in the administration, property seized from Jews, and exclusive use of parks, public phones, and taxis. Public transport and cinemas were also segregated and notices appeared on shops declaring “no Poles or Jews.” 4

Ethnic Poles, as members of the weaker Slavic race, were to serve as laborers. Hitler considered them to be Aryans with some Germanic blood that had been diluted by mixing with other races. Tens of thousands of Poles were pressed into work in the Reich that autumn. Killing squads known as the Einsatzgruppen preempted resistance by rounding up and shooting some 20,000 members of the Polish educated and professional classes—lawyers, teachers, doctors, journalists, or simply anyone who looked intellectual—and buried their bodies in mass graves. Newspapers were censored, radios banned, and high schools and universities closed on the basis that Poles only needed “educational possibilities that demonstrate to them their ethnic fate.” 5

John Gilkes

At the bottom were Jews, whom Hitler didn’t consider to be a race at all, but rather a parasitic subspecies of human bent on destroying the German people. Hitler had threatened Europe’s Jews with annihilation in the event that “international Jewish financiers” provoked another world war. But in the autumn of 1939, the Nazi leadership was still formulating its plans toward them. The occupation of Poland had brought two million Jews—ten times more than lived in Germany—under Nazi control. The deputy head of the SS, Reinhard Heydrich, advised units in September that the Jewish problem would have to be dealt with incrementally. He issued orders for Jews to be concentrated in cities ready for their deportation to a reservation along the new border with the Soviet Union. In the meantime, Jews were required to wear a Star of David on their sleeve or chest, mark their shops and businesses accordingly, and were subjected to continual harassment. “A pleasure, finally . . . to be able to tackle the Jewish race physically,” Frank declared in a speech that November. “The more that die, so much the better.” 6

Polish women on their way to be shot, 1939.

Courtesy of Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe.

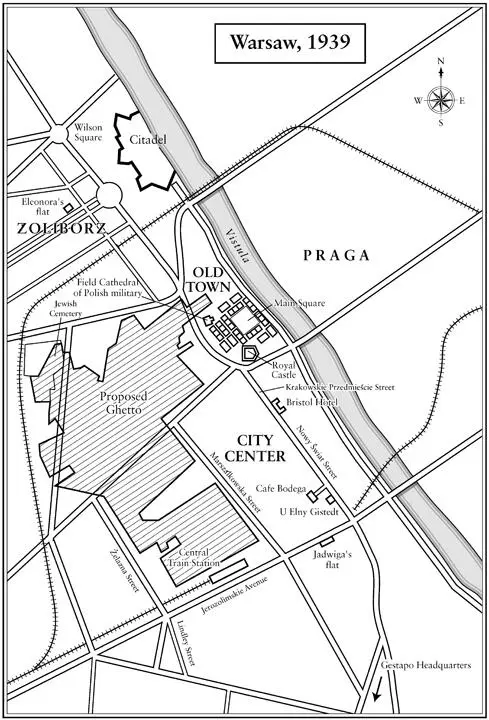

Witold almost certainly noticed Frank’s official decrees plastered on lampposts around the city and understood that the Germans meant to destroy Poland by tearing apart its social fabric and pitting ethnic groups against one another. But he also saw encouraging signs of resistance: stickers declaring, “We don’t give a damn” (a direct translation of the Polish idiom is: “We have you deep in our ass”) and a giant poster of Hitler in the city center that had sprouted curly whiskers and long ears. On November 9, Witold contacted his coconspirator Jan Włodarkiewicz and arranged a meeting of potential recruits at his sister-in-law’s flat in the northern suburb of Żoliborz. Witold hurried through the rainy streets trying to beat the 7 P.M. curfew. 7

His sister-in-law, Eleonora Ostrowska, lived in a two-room apartment on the third floor. Żoliborz was relatively untouched by the bombs, although the windows of most apartments were blown out and the electricity wasn’t working, so Witold had to wait for someone to enter in order to get in. Eleonora showed him inside with her two-year-old son, Marek, at her feet. The two had met only briefly before. She was a charming, tough thirty-year-old, her dark blond hair pulled back into a bun, with thin lips and pale blue eyes. Her husband, Edward, Maria’s brother, was a cavalry officer who’d been missing since the start of the war, leaving her to take care of Marek and hold down a job at the agricultural ministry, one of the few government departments that the Nazis hadn’t abolished. 8

Entrance to 40 Wojska Polskie Avenue.

Courtesy of PMA-B.

Jan was one of the next to arrive, wheezing and shuffling up the steps. He’d taken a bullet through the chest on his way to Warsaw that somehow missed his vitals, and had been laid up at his mother’s. Half a dozen more followed, mostly officers and student activists selected by Jan. Eleonora had put brown paper over the windows, but it was cold and they kept their coats on. They gathered around the living room table where Eleonora had lit a candle. 9

Jan had reached some stark conclusions about their situation: Poland had lost because its leaders had failed to create a Catholic nation or use the country’s wellspring of faith against the invaders. Jan believed they needed to see in Poland’s defeat an opportunity to rebuild a country around Christian beliefs and awaken the religious fervor of the younger generation. He harbored ambitions to appeal to right-wing groups, but for now he fashioned a broad rallying cry of resistance to the country’s double occupation. 10

Eleonora Ostrowska, 1944.

Courtesy of Marek Ostrowski.

Witold certainly shared Jan’s anger at the Polish government, a common sentiment in Warsaw, but he rarely sought to share his faith with others and feared that an avowedly religious mission would alienate potential allies. For the moment, he was probably more focused on assessing the viability of building a secret and effective resistance. 11

They talked strategy late into the night before getting to the subject of their roles. Jan would lead; Witold would serve as chief recruiter. They would call themselves Tajna Armia Polska, the Secret Polish Army. At dawn they stole out of the apartment to the Field Cathedral of the Polish Military, a Baroque church on the edge of the Old Town. They knew a priest there and asked him to witness their oath. Getting down on their knees at the dimly lit altar, they swore to serve God, the Polish nation, and each other. They received a blessing in return, before emerging, bleary-eyed but elated. 12

***

Winter came early that year as Witold started to recruit. The snow fell in flurries, the Vistula froze solid, and a hundred resistance cells sprang up across the city. There were other officer-led groups like his, as well as Communist agitators, trade unionists, artist collectives, even a group of chemists planning biological warfare. The Germans had commandeered popular meeting spots like the Bristol and Adria hotels, but new places sprang up that became known as underground haunts. At U Elny Gistedt’s—a restaurant named after the Swedish operetta singer who’d set the place up to employ her out-of-work artist friends—groups of conspirators sat hunched over their tables in fur coats. The conspirators mostly knew each other, and shared the latest news from around the city or scraps gleaned from illegal radio sets about the Allied counter-offensive expected in the spring. 13

At the same time, a black market flourished near the central railway station trading in clothes and food, dollars, diamonds, and forged papers. Peasants from the countryside smuggled goods in the hems of their clothing, hidden pouches, and bras. 14

“Never before have I seen such oversized busts as in Poland at this time,” recalled Stefan Korboński, an underground member. One enterprising smuggler brought butchered pigs into the city hidden in coffins. The Germans, busy setting up their administration, offered only cursory inspections, and even when someone was discovered they might get off with a bribe or, on rare occasions, a little wit, as was the case with the smuggler who tried to disguise a trotter as a peasant woman. “When discovered by gendarmes, even they, bereft though they were of all sense of humor, nearly died of laughter,” wrote Korboński. 15

Читать дальше