They made it to a cousin’s house in a neighboring town, where they rested a week and tried again. This time they hired a guide to sneak them across the border at night. It was subzero, and a full moon lit the wind-scourged no-man’s-land. Halfway across Andrzej had stumbled and fallen against a roll of barbed wire that snagged his sheepskin jacket. At that moment a German searchlight had swept the area and caught them as they struggled to free the jacket. They were quickly rounded up but were lucky: the border guards who collected them showed little interest in their case and let them pass. 30

They had arrived in Ostrów Mazowiecka to find it devastated by the unfolding German racial project. Maria was told that on November 11, the Germans had marched 364 Jewish men, women, and children to woods outside the town and shot them, one of the first such massacres of its kind. The execution site was only a mile or so from her mother’s house, and adjoined the family orchard where Andrzej liked to play (despite being told not to go there, Andrzej did, and found a little boy’s sodden cap among the trees). 31

Witold did what he could to make sure his family was properly settled and then returned to Warsaw with a new urgency, only to discover Jan flirting with anti-Semitic views. Witold knew Jan wanted to produce a newsletter on behalf of the group for some time. The underground was awash with publications of different political hues—eighty-four titles were published in 1940—but Jan wanted a newsletter that would focus on the moral underpinnings of the resistance. At least that was how he pitched it to the likes of Witold and Jadwiga Tereszczenko, a friend of Jan’s who’d agreed to be the editor. 32

Witold wasn’t opposed to the idea, and in fact helped arrange one of the distribution points at a grocery shop on Żelazna Street near where he was staying. But in the first issues of Znak , or “The Sign,” he read articles that seemed lifted straight from the manifestos of prewar right-wing groups: strident talk of a Polish nation for the Poles, and creating a true Christian country, views that were disturbingly close to those of the ultranationalists who saw the Nazi occupation as a means of getting rid of the Jews for good. 33

Witold explained as tactfully as he could to Jan that Poles must rally together in the face of mounting German repression. Jadwiga also raised the issue of anti-Semitism among Poles with other editors during late-night writing sessions in her flat, but they dismissed her concerns: the Jews didn’t know whose side they were on and were better off gone. Meanwhile, the walls were going up around the ghetto and Jewish families were being forced to relocate, including Jadwiga’s next-door neighbor. Rather than helping them, ethnic Poles in her block were taking whatever was left behind. There did need to be a moral awakening among Poles, Jadwiga believed, starting with the edict to “love thy neighbor.” 34

Yet Jan was unrepentant and started work on a right-wing manifesto for the organization that he appeared to want to turn into a political movement. He also began talks with nationalist groups about a possible union, including one whose members had sounded out the Germans about forming a Nazi puppet administration. Jan was clearly losing his way, and Witold felt compelled to go behind his friend’s back to stop him. 35

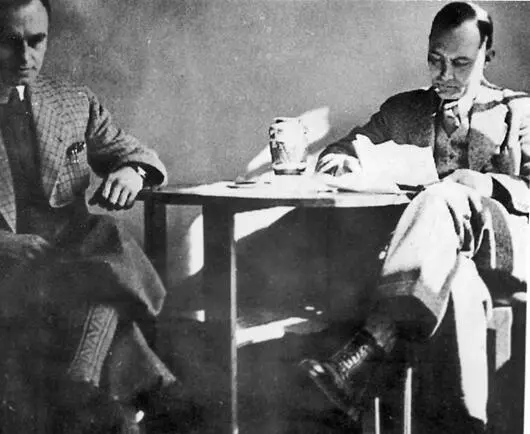

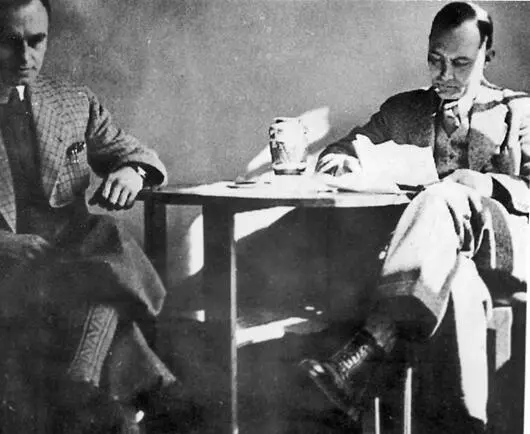

Witold and Jan, c. 1940.

Courtesy of the Pilecki family.

At some point that spring, Witold sought out the head of the rival Związek Walki Zbrojnej, Colonel Stefan Rowecki, to discuss joining forces. The forty-five-year-old had supported the creation of an underground civilian administration that answered directly to the Polish exile government in France, and which regularly issued calls for a “truly democratic” country with equal rights for Poland’s Jews. Rowecki, a self-professed Sherlock Holmes fan who deployed a variety of disguises, rarely expressed his own views but was an astute observer of the national mood. He had already written to Polish leadership in France of his concerns that the Nazis were deliberately stoking racial hatred to divert Poles from anti-German activity. There had been a significant escalation in attacks by ethnic Poles on Jews, Rowecki reported, and he was concerned that a right-wing politician might emerge as a German stooge who would use the persecution of the Jews to justify their position. 36

Like Witold, Rowecki had few illusions about what the underground could achieve against the might of the occupiers. But he felt that their resistance served a deeper purpose of rallying morale as they slowly built capacity. In the meantime, he wanted the underground to start documenting Nazi crimes to inform the West and pressure the Allies to act. 37

Rowecki had established a network of couriers who traveled in secret over remote mountain passes of the Tatras and on to France. So far, his reports had yet to stir the imagination of Western leaders, although the Germans were embarrassed by some of the revelations, and had even released one group of academics they’d detained after an international outcry. Rowecki believed that the accumulating details would help stiffen British and French resolve. 38

Witold came away impressed by the caliber of the quiet, secretive man and convinced of the need to submit to his authority. But Jan immediately dismissed a merger at their next meeting, pointing out that he had sent his own courier to the Polish exile government for endorsement. He then announced the manifesto he’d prepared was to be jointly signed by several fringe groups. 39

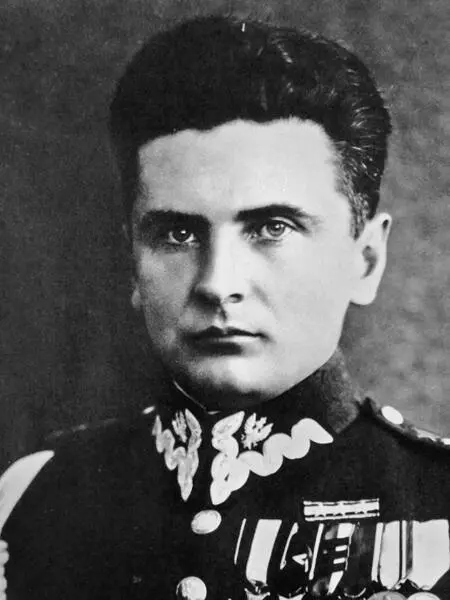

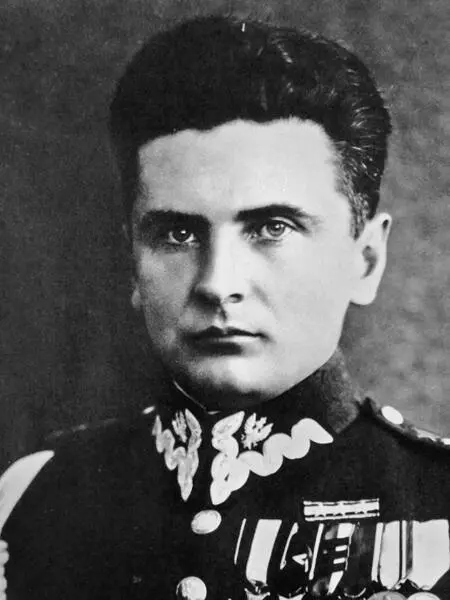

Stefan Rowecki, prewar.

Courtesy of the Polska Agencja Prasowa.

“Such a declaration would destroy all our work!” Witold exclaimed. “Let us focus on the armed struggle. We can worry about constitutional matters later.” 40

Jan looked taken aback. He’d been counting on Witold to fall into line. Instead, several others agreed with Witold, including the group’s new chief of staff, a doughty colonel named Władysław Surmacki. Jan capitulated and agreed to meet with Rowecki, a victory of sorts for Witold. 41

But Jan pressed ahead with his declaration, which was just as divisive as Witold had feared. There was no reference to Jews or other minorities in the article, but the subtext appeared clear. “Poland has to be Christian,” the declaration announced, “and Poland has to be based around our national identity.” Those opposed to such ideas should be “removed from our lands.” Witold knew that their partnership was ruined. “On the surface we agreed to keep on running the organization,” Witold recalled, but there was no hiding the “deeper resentment.” 42

Władysław Surmacki, c. 1930.

Courtesy of PMA-B.

***

On May 10, Hitler’s forces swept into Luxemburg and the Low Countries on their way to France. This was the moment the underground had waited for when the combined might of the Allies would take on the Germans, and either defeat or else distract them enough to make an uprising in Poland worthwhile. Jan’s mother had set up an illegal radio in her flat. They gathered to listen, eagerly at first, and then with increasing grimness as the BBC reported that German forces had routed the British at Dunkirk and swept into Paris. It soon became apparent that Germany was about to inflict a cataclysmic defeat on the French, and that the war was going to stretch on indefinitely. 43

Читать дальше