James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

From the concert hall, we went directly to Stockholm's massive 1930s city hall for the Nobel banquet, which was held in the Golden Hall. Running the entire length of the beautiful room with vaulted ceilings was a very long table where all the laureates were seated with their spouses as well as the royal entourage and members of the diplomatic corps. Placed at its center facing each other were the king and queen. I was seated on the queen's side. While Max, John, Francis, and John Steinbeck all had princesses next to them, my conversation bits were to be alternately directed to the wives of Maurice and John Steinbeck. Talking across the table made no sense, because of both its width and the alcohol-enhanced din created by more than eight-hundred celebrants. During the dinner, the chairman of the Nobel Foundation, Arne Tiselius, proposed a toast to the king and queen; the king, in

turn, proposed a minute of silence to honor Alfred Nobel's grand donation and philanthropy.As soon as dessert was finished, John Steinbeck went to the grand podium overlooking the hall to deliver his Nobel address. In it he emphasized man's capacity for greatness of heart and spirit in the endless war against weakness and despair. The Cold War and the existence of nuclear weapons silently lurked behind his message of the writer confronting the human dilemma. He saw humans taking over divine prerogatives: “Having taken god-like powers, we must seek in ourselves for the responsibility and the wisdom we once prayed some deity might have.” Ending his oration, he paraphrased St. John the Evangelist: “In the end is the Word, and the Word is man, and the Word is with men.”

I became increasingly nervous and could not listen attentively, since in just a few minutes I was to be up on the podium to offer the response of the laureates in physiology or medicine. I hoped my extemporizing would rise above platitudes. Only after I was back at my seat did I relax, knowing that I had spoken from the heart. I was pleased at my last sentences, in which I had aimed for the cadence of one of JFK's better speeches. Graciously Francis then passed across the table his place card with a note on the back: “Much better than I could have done.—F.” I could then enjoy John Kendrew expressing his joy at being part of a group of five men who had worked and talked together for the past fifteen years and could now come together to Stockholm on the same happy occasion. Then the party moved to the floor below for dancing, most of it done by the white ties and gowns of the Karolinska medical students.

Late the next morning the laureates in science gave their formal Nobel addresses. Francis, Maurice, and I were allotted thirty minutes each. It was not an occasion for questions from our audience of mostly fellow scientists. At seven-thirty that evening, I went alone to the palace for a second royal reception at which protocol had again somehow failed to place me beside a princess. This time I was between the wife of the Swedish prime minister and Sibylla, the wife of the Crown Prince Gustav Adolf, who had died in a 1947 airplane crash when his

daughters, the princesses, were still young girls. I found it easier to converse with the prime minister's wife than with Sibylla, whose native language was German. Sibylla ate practically nothing, perhaps imagining her still comely figure metamorphosing into the stereotypical one for royal consorts of the past century

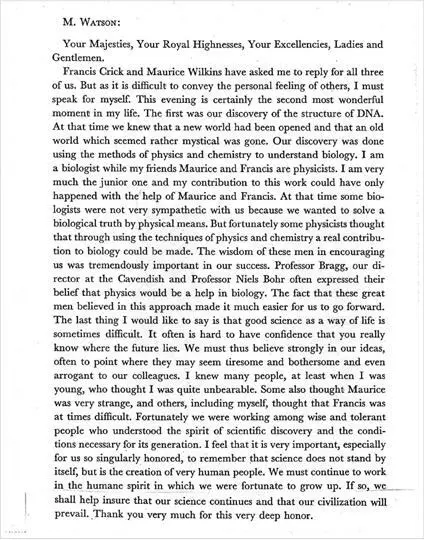

The transcript of my Nobel speech

Before lunch the next day at the American ambassador's residence, I was taken to the Wallenberg's family Enskilda Bank to exchange my advance check of 85,739 kroner for one denominated in dollars, approximately $16,500. Earlier at Nobel House, I had been given a bronze copy of my gold Nobel Medal that I could safely leave lying about my desk. There had been past thefts of the gold originals, and I was urged to keep it in a bank vault. Seemingly hundreds of photos from the past days’ festivities were then shown so that I could order copies of the ones I wished. Immediately my eye alighted on one of Francis and Princess Désirée, sitting across from me at the Nobel banquet.Ambassador J. Graham Parsons greeted me graciously, giving no sign of the hawkish inclinations that had reputedly caused his recent banishment from the Washington corridors of Southeast Asia decision making. Also welcoming us was our embassy's number two man, Thomas Enders, whom I asked if he was related to John Enders, the Harvard Medical School's polio specialist who had won the Nobel eight years earlier. In fact, this Enders was the Nobel laureate's nephew, happily no longer living behind the Iron Curtain as a junior diplomat in Poland.

Nobel Week concluded traditionally on Saint Lucia's Day. Like all the laureates, I was awakened by a girl in a white robe and a crown of flaming candles, singing the Neapolitan hymn that long ago became virtually synonymous with this Swedish winter festival. With our father departing that afternoon for a week in France, Betty and I again put on formal finery for the Luciaball of the Medicinska Föreningen. At dinner reindeer was served as the main course. Afterward our party moved on to a much smaller private affair that let me banter long with Ellen Huldt, a pretty dark-haired medical student, with whom I then arranged to have dinner the next night.

Before getting into a taxi to fetch Ellen, I penned a letter to President Pusey, telling him of my visit that afternoon to the Royal Palace to see Princess Christina. With my diplomatic escort, Kai Falkman, I entered one of its private reception rooms to find her with her mother, Sibylla. Over tea and cakes, I related how much I enjoyed teaching the lively students of Harvard and Radcliffe and assured the mother that

her daughter would greatly enjoy a year at Radcliffe. After returning home I sent back to Sweden several copies of Harvard's newspaper, the Crimson, to let Christina have a feel for Harvard undergraduate life.As Nobel week ended, I was to depart for a visit to West Berlin arranged by the State Department, where my lecture before its scientists was to be yet another reafflrmation of the United States’ unswerving commitment to those peoples trapped by the Cold War. Before flying there via Hamburg, I spent my last night in Sweden with John Steinbeck and his wife at the studio home of their friend the artist Bo Beskow. Liking Ballet School, one of his semifigurative blue paintings, I found its price to be within my somewhat improved means and arranged for it to be sent to Harvard. It long hung on the wall of the Biological Labs library.

In Berlin, I stayed for three nights at the guesthouse of the Freie Universität, a postwar creation sited among the buildings that once housed many of Germany's best scientists before Hitler. Until the Nazis came to power, Leo Szilard and Erwin Schrödinger had lectured on quantum theory there, with the voice of Einstein always figuring prominently in any discussion. Now of the past giants, only the Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Otto Warburg remained.

Soon to greet me was Kaky Gilbert, who the year before her Radcliffe graduation had assisted Alfred Tissières and me with experiments on messenger RNA. As a student at the Freie Universität, she would be showing me West Berlin. Unfortunately, she could not get permission to join me on my half day's visit to East Berlin, where I was surprised by the extraordinary Hellenic and Assyrian collections of the vast Pergamon Museum. Kaky did, however, accompany me to lunch at the residence of the head of the American mission in West Berlin. There I met the Prussian-acting Otto Warburg, whose legendary contribution to enzymology made him the most talked-about biochemist of our time. Though half Jewish, Warburg's longtime interest in cancer had led Hitler, always paranoid about contracting it, to let him continue working in Berlin throughout the war. He told me that my Harvard colleague George Wald was much too interested in philosophy, in contrast to his total lack of interest in it. Later, when

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.