James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

10. MANNERS APPROPRIATE FOR A NOBEL PRIZE

INDIVIDUALS nominated for Nobel Prizes are not supposed to know their names have been put forward. The Swedish Academy, which judges candidates and awards the prize, makes this policy very explicit on their nomination forms. Jacques Monod, however, could not keep secret from Francis Crick that a member of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm had asked him to nominate us in January for the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. In turn, Francis, when visiting Harvard that February to give a lecture, let the cat out of the bag at a Chinese restaurant where we were having supper. But he told me we should say nothing to anyone, lest it get back to Sweden.

That we might someday get the Nobel Prize for finding the double helix had been bruited about ever since our discovery. Just before my mother died in 1957, she was told by Charles Huggins, then the University of Chicago's best-known physician-scientist, that I was certain to be so honored. Though many were initially skeptical that DNA replication involved strand separation, this doubting chatter went silent after the 1958 Meselson-Stahl experiment demonstrated that very phenomenon. Certainly the Swedish Academy had no doubt as to the correctness of the double helix when they awarded Arthur Kornberg half of the 1959 Physiology or Medicine prize for experiments demonstrating enzymatic synthesis of DNA. When photographed shortly after learning of his Nobel, a beaming Kornberg held a copy of our demonstration DNA model in his hands.

As the October 18 date for announcing the year's Nobel in Physiology

or Medicine approached, I was naturally jittery. Conceivably the responsible Swedish professors had requested more than one nomination, reflecting split opinions during preliminary caucusing. Nonetheless, as I went to bed the night before the prize announcement, I couldn't help fantasizing about being awakened by an early morning phone call from Sweden. Instead a nasty cold I'd caught awakened me prematurely, and I was depressed to realize at once that no word had come from Stockholm. I remained shivering under my electric blanket, not wanting to get up when the telephone rang at 8:15 A.M. Rushing into the next room, I happily heard a Swedish newspaper reporter's voice tell me that Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins, and I had won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Asked how I felt, all I could say was, “Wonderful!”First I phoned Dad and then my sister, inviting each to accompany me to Stockholm. Soon after, my telephone began to buzz with congratulatory messages from friends who had already heard the news on the morning broadcasts. There were also calls coming from reporters, but I told them to try me at Harvard after I'd given my morning virus class. I felt no need to rush through breakfast with Dad, so the class hour was almost half over when I walked in to find an overflowing crowd of students and friends anticipating my arrival. The words Dr. Watson has just won the Nobel Prize were on the blackboard.

The crowd clearly did not want a virus lecture, so I spoke about feeling the same elation when we first saw how base pairs fitted so perfectly into a DNA double helix, and how pleased I was that Maurice Wilkins was sharing the prize. It was his crystalline A-form X-ray photograph that had told us there was a highly regular DNA structure out there to find. If Linus Pauling's ill-conceived structure had not gotten Francis and me back into the DNA game, Maurice, keen to resume work on DNA the moment Rosalind Franklin moved over to Birkbeck College, might by himself have been the first to see the double helix. He was temporarily in the States when the prize story broke, and held his press conference next to a big DNA model at the Sloan-Kettering Institute. The long-standing rule that a Nobel Prize can be shared by at most three individuals would have created an awkward if not insolv-able dilemma had Rosalind Franklin still been alive. But having been

tragically diagnosed with ovarian cancer less than four years after the double helix was found, she'd died in the spring of 1958.

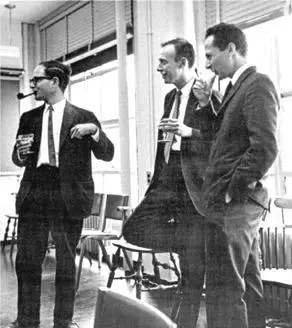

Celebrating my big news with Wally Gilbert (left) and Matt Mesekon (right)

After class ended, I soon found myself with a champagne glass in hand and talking to reporters from the Associated Press, United Press International, the Boston Globe, and Boston Traveler. Their stories were picked up by most papers across the country, clippings from which came to me through the Harvard news office. Often they were accompanied by AP photos showing me in front of my class or holding the hand-size demonstration model of the double helix built at the Cavendish back in 1953. Able to afford the luxury of modesty, I tried to downplay potential practical applications, saying that a cure for cancer was not an obvious consequence of our work. And with my stuffy head and hoarse voice quite apparent, I emphasized that we had not done away with the common cold. This became the quotation of the day in the October 19 New York Times. When asked how I would spend the money, I said possibly on a house and most certainly not on hobbies such as stamp collecting. To the question as to whether our work

might lead to genetically improving humans, I answered, “If you want to have an intelligent child, you should have an intelligent wife.”

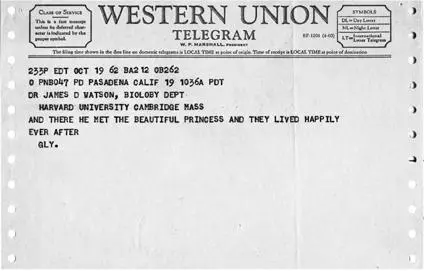

Richard Feynman s congratulatory telegram, signed with his RNA Tie Club code name, GLY

A number of the next day's articles described me as a boyish-looking bachelor whom friends found lively and kindly. Not surprisingly, some reports had bad gaffes such as Maurice's picture above my name, while others reported that I had worked during the war on the Manhattan Project, again confusing me with Wilkins, who had come to the United States in 1943 to work on uranium isotope separation at Berkeley. Naturally the Indiana papers played up my IU background, with the Indiana Daily Student quoting Tracy Sonneborn that I was a formidable reader with no tolerance for stupidity and a great respect for smarts. In a similar vein, the Chicago Tribune took pride in reporting my Chicago upbringing and appearance on Quiz Kids, quoting my father that it was through my childhood interest in birds that I got into science.

A hastily arranged evening blast at Paul and Helga Doty's Kirkland Place house allowed my Cambridge friends to toast my good fortune. Earlier I had talked by phone to Francis Crick, no less elated in the other Cambridge. Most of some eighty congratulatory telegrams

arrived over the next two days, while the next week brought some two hundred letters I would eventually have to acknowledge. Joshua Lederberg, whose Nobel Prize had come three years earlier and who'd lived through the pandemonium that goes with it, advised me to follow his trick of replying with postcards from Stockholm. As he was then briefly hospitalized, Lawrence Bragg, our old boss at the Cavendish, had his secretary write of his delight. Unique in addressing me as “Mr. Watson,” President Pusey wrote: “It seems almost superfluous to add my congratulations to the many friendly messages you will be receiving.” And I had to wonder whether I had been mistaken in backing Harvard's Stuart Hughes for the Senate when not he but Edward M. Kennedy took the time to write, “Your contribution is one of the most exciting scientific achievements of our time.”There were also the inevitable letters expressing not congratulations but the writer's personal hobbyhorse. One from a Palm Beach man, for instance, declared that marriages between cousins are the cause of all the great evils that have afflicted mankind. Here I thought better of writing back to ask whether there had been any such marriages among his ancestors. Several days later, the managing director of the Swedish company that manufactured Läkerol throat pastilles wrote to say that he was having an export carton sent direct from his New York distributor. He noted his product's absence of harmful ingredients, which feature made it suitable for everyday use even in perfect health. Soon I began popping several of his pastilles each day after my cold turned into a sore throat. Unfortunately, they were of no effect, my throat misery persisting through days of celebration.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.