James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Watson - AVOID BORING PEOPLE - Lessons from a Life in Science» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

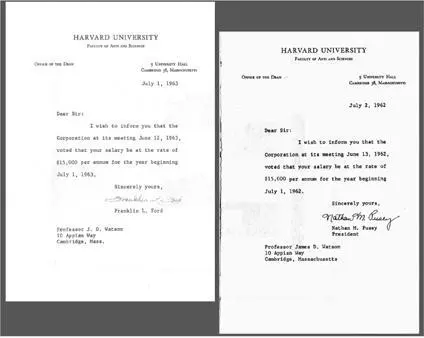

Venting my wrath to student friends who wrote for the Crimson would be fun but likely to backfire and generate the official reply that Harvard never could adequately reward all the important ways the faculty enrich the academic milieu. Instead I talked to Harvard's best chemist, Bob Woodward, who was himself bound to receive the Nobel Prize soon. Attempting to calm me down, he told me he thought Harvard's failure to reward me reflected bad judgment on the part of our mediocre president as opposed to a deliberate insult. Bob offered to write Franklin Ford that if he were similarly treated, he would feel equally upset toward those who led Harvard. Later, Franklin Ford called me to his office to say that no insult had been intended—rather, priority had been given to rewarding other professors whose salaries

were particularly low. The following year my salary went up by $2,000. My Spartan existence at 10 Appian Way, then as before, had allowed me routinely to spend less than I was earning. I thought about money only when I wanted to acquire for the walls of my apartment a painting or drawing beyond my means. Still, I would have been $1,000 poorer before taxes every subsequent year had I not spoken up about my displeasure.

The letters that bookended the year I got a Nobel Prize but no raise from Harvard

More crucial to my morale than salary was how the science in my lab was going. Here I had cause for pleasure in the quality of my latest batch of graduate students—John Richardson, Ray Gesteland, Mario Capecchi, and Gary Gussin. With messenger RNA discovered, they knew how to proceed on their own. Underlying many of their successes was increasing use of phage RNA chains as templates for protein synthesis. To start us off, Ray Gesteland worked with Helga Doty to determine the molecular character of the RNA phage R17, whose RNA

component of only some three thousand molecules most likely coded for only three to five different protein products.The key surprise of the summer of 1963 was finding that RNA phages start their multiplication cycle through attachment to sex-specific thin filaments (or pili) coming off the surfaces of male E. coli bacteria. Such filaments are absent from female E. coli cells, explaining the until then mysterious fact that RNA phages grow only on male bacteria. Doing the electromicroscopy was Elizabeth Crawford, a summer visitor from Glasgow, with her molecular virologist husband, Lionel. Soon after their arrival, the three of us went up to the White Mountains, where we unintentionally aroused the ire of a nest-guarding goshawk that repeatedly dive-bombed us as we came down from a not undemanding walk up to the four-thousand-foot Carter's Dome.

Just before Labor Day, I flew to Geneva on my way to lecture at a NATO-sponsored molecular biology summer school at Ravello, Italy, across the bay from Naples. Among the other lecturers were to be Paul Doty, Fritz Lipmann, Jacques Monod, and Max Perutz. My high-ceilinged room in the Villa Cimbrone would have been perfect but for the nightly ravages of mosquitoes. Good fortune gave me as one of the sixty students the young German protein chemist Klaus Weber, then experimenting on the enzyme ß-galactosidase for his Ph.D. at Freiburg. Klaus had come to Ravello to broaden his knowledge of nucleic acids and by the two-week program's end he'd accepted my invitation to come the following year to work on RNA phages in my Harvard lab.

At completion of the summer session, Leo Szilard flew down from Geneva to help lead further discussions about establishing in Europe a meeting and course site similar to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. In Europe primarily to promote his latest scheme for preventing the nuclear annihilation of the planet, Leo came to Ravello on his way to a Pugwash disarmament meeting in Dubrovnik. Among those also briefly staying at the Villa Cimbrone were Ole Maaloe from Denmark, Sydney Brenner and John Kendrew from Cambridge, Ephraim Katchalski from Israel, and Jeffries Wyman, now living in Rome. By the end of the two-day meeting, widespread support existed

for forming a European Laboratory of Fundamental Biology as well as a European Molecular Biology Organization of some one hundred to two hundred leading European biologists.In a Rome art gallery on my way back, I lacked the courage to buy an almost affordable surrealist painting by an artist then unknown to me, Victor Brauner. During the following days, however, I acquired a small Paul Klee drawing from Gallery Moos, located below Jean Weigle's Geneva flat, and several André Derain drawings from Galerie Maeght in Paris. A week later, Princess Christina saw my new works of art at a small Sunday afternoon party I gave to help introduce her to Harvard life. Accompanying her was Antonia Johnson, the daughter of a leading Swedish industrial and shipping family, also to spend the coming year in the Radcliffe quad. To make the occasion more friendly, I invited some of my students, particularly those doing undergraduate research. But forty-five minutes later, when Christina and Antonia went off to another welcoming occasion, I remained unsure whether we would have reason to greet each other with more than a nod in passing during the year ahead. Neither Christina's nor Antonia's course choices were likely to bring them to a Harvard science building. On the other hand, Christina was likely to be friendly with my Radcliffe friend and future tutee Nancy Haven Doe, who had gone to the Spence School. She came from the New York social scene, which Radcliffe's first princess was bound to sample.

In the meanwhile, I became increasingly immersed in Biology Department politics. Carroll Williams was no longer chairman, having been succeeded by the into-Harvard-born behavioral biologist Don Griffin, who specialized in bat navigation. After being a Harvard junior fellow, he quickly rose in the academic ranks at Cornell before being called back in 1956. Don had natural affinities with Harvard's organismal biologists, so it was not anticipated that his first major goal as chairman would be to reduce the power of Harvard's separately funded biology museums, such as the Museum of Comparative Zoology and the Harvard Herbarium. Until this landmark turnabout, tenured museum scientists not only chose future museum curators but also had a say as to appointments to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS).

Back in June 1963, the tenured faculty, following Don's lead, voted that only professors supported by FAS monies would have automatic voting rights. At the same time, they opened up the possibility of key museum members having three-year terms on the Committee of Permanent Professors if so approved by two-thirds of the FAS-funded faculty. In this way, widely respected museum scientists such as the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr would retain voting rights. Carroll Williams, who still held much political power in the department, later tried hard to have the decision reversed. If the museum deadbeats were removed from the department scene, Carroll would no longer be seen as a neutral party in the tension between old-fashioned organismal biologists and the new group of molecular biologists. Instead he would be perceived as the leader of a conservative biology caucus openly determined to stop DNA-centered work from ever dominating Harvard's biology. It remained unclear whether Carroll would prevail until the fall of 1963, when a letter came from Franklin Ford reaffirming the opinion that only faculty paid by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences should vote on their respective department appointments.These sensible voting qualifications, however, did not adequately guarantee first-rate appointments to the biology faculty. At least one-third of the Biological Laboratories remained unchanged since its construction thirty years earlier. Particularly out of date were its teaching labs, library, animal quarters, and machine shops. Moreover, the practice of relying on the senior faculty's government grants to renovate the out-of-date labs of incoming junior faculty put the latter cohort in a servile role. New funding would have to materialize from the Faculty of Arts and Science, not just from federal grants, if Harvard was to hold its own with Stanford, Caltech, MIT, and Rockefeller. Keith Porter, Paul Levine, and I prepared a report on facilities, which Don Griffin passed on to Franklin Ford. In it we outlined three possible scenarios for action. The first proposed extensive remodeling of the Biolabs; the second, a new five-story wing to the east; and the third, a ten-story building whose site demanded demolition of the historic brick Divinity School residence hall on Divinity Avenue, to the front of the Biological Laboratories.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «AVOID BORING PEOPLE: Lessons from a Life in Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.