On a good day, a trip across the Cascades means lively turbulence. On November 12, 2008, the atmosphere over the mountains was a frightening world of invisible whirlpools and breaking waves, with wind gusts exploding against the little Cessna like aerial depth charges. Colton later told a friend that as he flew into the mountains, the clouds closed around him, describing conditions as a whiteout. A full-on flush of fear replaced his euphoric buzz and screamed at him to either panic or freeze up—two decidedly fatal options for a pilot. One miscalculation on this already remarkably reckless flight would likely be Colton’s last. Turning around at the first hint of weather trouble would have been the only smart option, but also meant a much greater chance he’d go back to prison—and that’s not how he’d planned to play this game. In his mind, it was all or nothing. So he kept going.

Colton claims that at one point the Cessna fell into a stomach-churning nosedive toward the ground, plummeting from thirteen thousand to six thousand feet. His fright took physical form as his last meal splattered across the cockpit while he fought to keep the plane in the air.

He says he believes it took the intervention of a higher power, but he finally regained control. After what surely seemed like an eternity, the skies began to clear. Colton made it across the highest part of the Cascades and into the drier air east of the mountain range. The winds remained deadly strong, but the turbulence grew less violent. There hadn’t been any question of the plane holding together, just the pilot. But he’d made it this far. Gravity now guaranteed the plane would come back to earth—in how many pieces was up to Colton.

Around 9 a.m., the Cessna left the state of Washington and crossed into the sovereign Yakama Nation, a 1.3-million-acre reservation east of Mount Saint Helens belonging to the Palouse, Sk’in-pah, and twelve other tribes of the Columbia River plateau. It’s an area famous for having one of the world’s highest number of UFO sightings, with local aliens reportedly fond of appearing as hovering, “inquisitive” balls of light that sometimes follow motorists. In the 1960s, the reservation was also ground zero for Bigfoot sightings.

It’s good country for wildlife—regular earth animals as well as the mythical. Stands of cedar, ponderosa pine, and tamarack thin out to sagebrush as the hills climb into bald mountains. The land supports large herds of elk and black-tailed deer, along with mountain goats and lots of black bears. Thousands of wild horses also roam free on the reservation. Whether the outlaw who’d rustled the bucking Cessna in order to escape the angry sheriff acknowledged the Wild West symbolism or not didn’t matter. Colton was just searching for a place to put the plane down.

At 9:15, a small band of Yakama hunters stalking elk looked up and saw a plane circling over Mill Creek Ridge, sacred tribal ground in the shadow of 4,710-foot Satus Peak. Totally off-limits to outsiders, it’s an area the Yakama call the Place Where the Wind Lives.

To a pilot, it doesn’t matter much where the wind lives, but knowing its direction and strength is absolutely critical. Airfields have windsocks and weather instruments. Someone attempting to land out in the wild, though, has to gauge wind speed by reading natural signs: bending grasses, rippling ponds, blowing leaves. On this day, with gale force winds howling around Satus Peak, you were just as likely to see flying coyotes.

The Cessna continued to buzz the area for nearly a half hour as Colton scouted a flatish spot, tried to read the wind sign, double-checklisted landing procedures, and double-gut-checked himself. He had to mentally prepare for what pilots call an off-airport landing, which translates into English as, “Oh shit, I’m about to crash on a hillside.”

Landings—even on a perfectly level runway—are where the experience gained by repeated, supervised practice combines with a gradually earned seat-of-the-pants feel for the uneasy interface between air and ground to make an art out of the science of flight.

THE PREFERRED EMERGENCY LANDING—exactly like the preferred nonemergency landing—takes place into the wind for the simple reason that the plane will be moving slower in relation to the ground. The tyrannical side of physics says that the energy of an impact rises as a square of speed. Where the guts hit the ground, that means the faster you’re moving the greater the likelihood of crumpling, cartwheeling, fracturing, and bleeding.

The tribal police chief who rushed to the site said the wind sweeping across the ridge that morning was blowing so strong, “it was hard for a man to stand up.” Converted to mph, that’s about 50, which meant a 100 mph speed difference between landing into or with the wind.

In a steady 50, an experienced pilot could walk the plane in and gently touch down moving at only 10 or 15 mph over the ground. Complications arise, however, when the wind and runway don’t line up—like at Mill Creek that day. Loads of wildly popular YouTube clips keyworded to “crosswind landing” show the spine-chilling final approaches forced on pilots when the wind blows across the runway. In a maneuver called crabbing, the plane flies straight toward the landing spot while its nose remains pointing into the wind like a big-haired woman crossing the street facing the wrong way just so her bouffant doesn’t get blown out of place. The plane literally flies sideways until it’s very close to the ground, where the wind generally calms and where, if all goes well, the pilot can bring the nose around at the last second to face forward.

The spot Colton finally chose to put down was a small clearing at the top of a rugged switchback road where tribal hunters park their 4 × 4s before hiking into the surrounding hills. Adjacent to the clearing was another thousand feet or so of relatively flat ground covered in scrub.

He almost made it.

Evidence on the ground showed that Colton apparently crabbed the plane toward the clearing but, possibly due to the unpredictable gusts, he hit short. The impact wasn’t very violent, leaving only a small gouge in the hard-packed dirt, but the landing wasn’t over. The Cessna bounced back into the air and leapt forward, flying over the clearing and up a slight hill, then crunched back to earth, its landing gear bending and metal skeleton twisting from the force of the crash. The plane shuddered across the ground, propeller slicing through sagebrush, until it nosed over into a ditch and finally came to an abrupt stop.

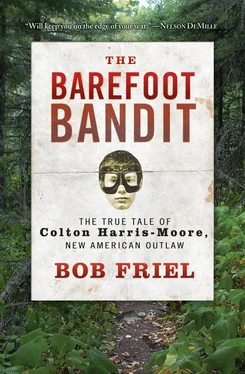

After nearly four hours, the alternately thrilling and terrifying flight was over and the pilot’s heart was still beating. He’d started the morning as Colton Harris-Moore, trailer-bred juvenile delinquent and petty thief. When he popped open the door of that stolen Cessna, though, and stepped into the wilds of Washington State haunted by the legends of Sasquatch, D. B. Cooper, Twin Peaks , and Twilight , he became Colt, the new millennium’s ballsiest outlaw.

Move over Bigfoot, meet Barefoot.

The hunters had seen the Cessna circle behind the ridge once again, but it didn’t reappear. They dialed the Yakama Tribal Police and told them a plane had gone down. The police chief himself, Jimmy Shike, jumped into his SUV and raced for the road that led up into the mountains.

They say “Any landing you can walk away from is a good one.” Colt ran away from his first solo landing. He headed for the trees and had barely gotten out of sight before Chief Shike drove up to the clearing.

The chief braced himself against the wind and strode up to the Cessna, which lay nose down, ass in the air, like a paper airplane stuck in the grass. The damage didn’t look too extensive at first glance, certainly survivable, but when he didn’t see a forlorn pilot sitting beside the pranged plane, Shike expected to find someone inside the cockpit, unconscious or worse.

Читать дальше