We’d just finished eating when the the Falcons, one of the Bahamas’ best party bands, came onstage and kicked into a cover of “Harbour Island Song,” which celebrates pink sand on your feet and dancing in the street.

The crowd pressing toward the stage parted for small groups of Bahamian women in impossibly tight jeans who wanted to get their booties bouncing. Then everything suddenly went silent… except for the drummer, who kept thumping the bass. Power to the sound system had gone out, cutting all the mics and guitars. I took the opportunity to sidle up to an RBPF chief inspector who stood out from the crowd in his bright tunic, red-sashed cap, and swagger stick. I started to say hello but double-taked because hidden behind the six-foot-three well-fed inspector was a scrawny patrolman about a foot shorter whose cartoonishly large round motorcycle helmet made him look like Marvin the Martian.

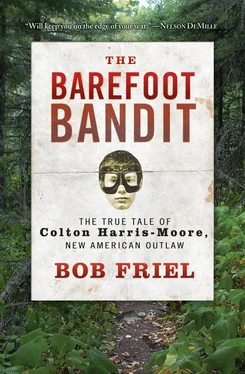

I nodded to Marvin, who stood stiffly at attention, ignoring me. I looked up at the chief inspector, wished him a happy Independence Day, then said, “I hear the Barefoot Bandit may be in the area.”

He looked me up and down, then finally said, “We have that information,” and he made it clear that was all I was going to get.

“EVERYTHING FOR US AT that point was just information, information, information,” says another chief inspector, Roston Moss. “There was only suspicion, no proof that this individual had landed on Eleuthera.”

At forty-two, Moss is already a twenty-five-year veteran of the Royal Bahamian Police Force. He’s spent most of his career in Nassau, home to the Bahamas’ meanest streets. At the end of February 2010, however, he was reassigned to Harbour Island. Normally, Briland, like Orcas, has a sergeant as its top cop, but there’d been a recent surge in crime, primarily what Kenny Strachan calls “looting.” In just the week before Moss arrived, the tiny island suffered eight burglaries. The night after he got there, robbers broke into an American tourist’s hotel room and hit him with a cutlass (the pirate-era name still used in the Bahamas for a machete). Since Harbour Island is the Bahamas’ prime destination for the rich and famous, it was extremely important to the country’s overall tourist industry to quell the crime wave and ensure it maintained its pastel-colored, celebri-quaint reputation. So Nassau sent the big man—Chief Inspector Moss stands six feet two inches, 295 pounds—to take over the station.

To assist him, Moss had eight regular officers and five reserve officers. They provided twenty-four-hour policing for the 1.3-square-mile island (compared to forty-square-mile Camano and fifty-seven-square-mile Orcas, both of which have fewer cops). As soon as he took charge, Moss also created a citizens advisory board to enhance the local crime watch.

Moss followed the events on Great Abaco after the stolen plane landed and knew about the boat found off Preacher’s. It wasn’t until Thursday, though, after the incidents and sightings at Three Island Dock, that he felt there was enough evidence the Barefoot Bandit was in his area to plan a search.

“On Friday, the ninth, at eight a.m., myself and seven officers started the manhunt in North Eleuthera,” says Moss. He split his men into two teams. Four drove around the top of the main island while Moss and three others searched by sea in a “go-fast boat,” scouting the beaches and rocky shorelines of Spanish Wells, Russell Island, Current Island, and Harbour Island.

“We were looking for footprints, a tent, a boat out of place… ,” says Moss. “But there was no sign of him.” Moss called off the search at 7 p.m. Friday, and resumed it Saturday morning, Independence Day. At five that afternoon, after again finding nothing suspicious, Moss stopped by the homecoming party at the Bluff to grab something to eat before heading back across to Briland.

AFTER NEARLY TEN MINUTES of solo boom, boom, booming, the Falcons’ drummer was drenched with sweat and looked about to pass out. I felt the same way. The cell towers were dead again. The only rumor we could scare up from anyone at the Bluff was another sketchy report about “the Bandit.” In the Bahamas, where so many people are often barefoot, almost everyone dropped that part of his nickname. The Bandit had maybe been spotted and maybe jumped off a boat and swam away. Didn’t sound likely.

A sudden screech of feedback and an electrician jumping three feet into the air after sticking something somewhere it shouldn’t have gone told me that the music wasn’t coming back for a while. Worse, the line at the drink booth was now twenty minutes deep.

Decision time. Whereas I’d made pretty good gut calls up to this point, I now made one of the worst.

I could take a chance and go over to Briland, maybe wind up having to spend the night on the beach if I couldn’t scare up a hotel room. We could go back to Coakley’s and wait until it closed and hope Colt showed up. I was going on thirty hours with no sleep, though, and if he did show, either my snoring would scare him away or I’d wake up with a bare foot drawn on my forehead. Option three won: go crash on Petagay’s couch.

We had people all over Eleuthera and the surrounding islands keyed up to call us if anything broke. Besides, what were the chances something big would happen in the next few hours? My gut told me he was still around and wasn’t planning on going anywhere tonight.

I hate being half right.

WE SWUNG BY THE airport on the way home. The police substation was empty, closed down. There was no security at all besides a chest-high chain-link fence along the runway. Commuter planes sat close to the tiny, dark terminal. Private planes—at least a dozen, including seven that Colt could fly—were farther down the tarmac. No lights, no police, no guards, and the world’s most successful plane thief somewhere within a few miles.

One of the planes on the field was a Cessna 400 that looked ready to leap into the air if you just tickled its tail. Suddenly I felt a strange urge to hop the fence, jump in, and take off.

At Petagay’s, I lay sweating beneath a ceiling fan with Bella’s dog, Jazzy, beating her tail against the couch as I fell asleep petting her.

BACK AT THE BLUFF, they finally fixed the sound system and Homecoming cranked up again. Ferry boats carried so many Brilanders over to Three Island Dock to go to the party that the couple of taxi vans still working couldn’t keep up with the flow. A crowd gathered near Coakley’s waiting their turn. One of the dock staff from Romora Bay Resort, nineteen-year-old Mauris Jonassaint, stood at the end of the dock talking to a friend while they waited for a ride. Suddenly they heard a boat engine coming toward them. The water was pitch-black except for the reflection of lights from Harbour Island, two miles away. Mauris says he figured it was a boat coming to pick someone up, but he could tell it was moving way too fast through the shallows.

A small white hull appeared out of the darkness headed right for the dock. Everyone started waving it off, shouting, “Whoa! Slow down!” When the driver got close enough to see that there was a crowd of people there, he immediately spun the boat around and started back for open water. “But he didn’t slow down,” says Mauris. “Just went back out at full speed. Mauris and the others watched, dumbfounded, as the tall white guy, in a light T-shirt and camouflage shorts, drove the little boat aground on a submerged rock within sight of the pier.

Colt had busted into a vacation home at Whale Point, a finger of North Eleuthera that points at Harbour Island from across an 850-foot-wide inlet. He broke in looking for one thing: a key to the shiny new thirteen-foot Boston Whaler Super Sport sitting on a trailer outside. He found it inside the garage, then muscled the half ton of boat and motor into the water and started its forty-horsepower Mercury outboard. The unsinkable $10,000 Whaler, designed for use as a yacht tender or as an all-purpose sport boat, wasn’t big enough to get Colt farther down the Bahamas chain, but it was plenty of boat for buzzing between the islands at the top of Eleuthera.

Читать дальше