ACROSS THE PIER FROM the taxi boats lies the tropically painted and grandly named Coakley’s International Sporting Lounge. Coakley’s consists of a small rum shop with a large covered patio and a pool table that provides the sport. Petagay and I pulled out two of the half dozen bar stools and ordered Kaliks. The name of the local beer comes from the sound of a cowbell, one of the most important instruments, along with whistles and goatskin drums, that create the Bahamas’ frenetically loud Junkanoo music.

Denaldo Bain pulled a couple of cold ones from a glass-front fridge that provided the brightest light in the nice, dark bar. Behind Denaldo, shelves held maybe a hundred liquor bottles, mainly rums. A TV suspended in the corner played a Schwarzenegger movie. Jamaican reggae pumping out of the stereo mercifully drowned the one-liners.

I asked Denaldo, who lays down rap songs when he’s not tending bar at Coakley’s, whether anything strange had happened on his side of the dock in the last few days. He said there’d been a break-in Wednesday night.

“What was taken?”

“Water, Gatorade, snacks… ”

“Any rum?”

“Nope.”

Colt.

“I know he was watching TV, too,” said Denaldo. “I came in the morning and the remotes and my chair were moved.”

Maybe Colt sat down to check to see if he was still making news. Denaldo pointed out the section of screened wall cut out so the Bandit could climb into the patio. After that, he said, Colt jimmied a deadbolt to get into the rum shop. He said that the same night, someone had also hit the administrative building at the center of the dock.

Denaldo, who lives across the water on Briland, said he’d also spotted Colt. “I saw him when I was closing up Wednesday night about ten o’clock. He was just about to go into the water. He stood up a little when we saw him—tall guy, slim, just shorts, bareback. The water taxi man was saying that the night before, someone trifle with the boats. So we look at this guy and no, no, not him, he wouldn’t trifle with the boats, didn’t look that way. This is just a tourist, just a tourist having fun. You know: love yourself. When we drove off, he went into the water.”

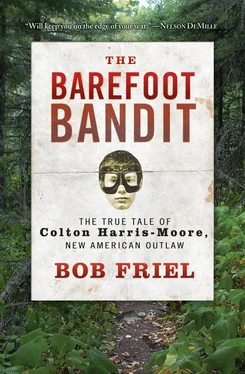

When the police came out to investigate the break-in at Coakley’s, they never mentioned the Barefoot Bandit and suspected the burglar was just a local troublemaker.

I ordered another Kalik and asked Denaldo what exactly had been taken. He pointed to cartons of bar snacks on top of the drink fridge. “He got Honey Buns and some of the Planters Go Packs, but his favorite was the Snickers.”

Ah, Snickers, the candy bar that fueled fifty burglaries. If he lived through this, I could see Colt’s first endorsement deal: “It’s tough staking out airports and marinas all night, so when I need an energy boost, I pull out a Snickers.”

“How about the drinks?” I asked.

“He took a few bottles of water and a couple Gatorades,” said Denaldo. “Oh,” he suddenly added, “and a few Heinekens and Kaliks.”

Regardless of whether Colt actually took the beers (which I kinda doubt), it was very interesting that he hadn’t emptied the place out. Why not fill his entire backpack with Snickers and water? If he’d been willing to carry a boat battery he could certainly handle a dozen bottles of Fierce Grape Gatorade to keep himself hydrated, and more Snickers to keep himself topped up on nougaty goodness. To me, that meant either he already had a campsite or an empty home stocked with food and water… or else he was supremely confident in his ability to forage what he needed whenever he needed it.

I looked up at all the candy bars and pastries Colt had left behind. “He’s going to come back here,” I told Denaldo.

He didn’t seem concerned. They’d put up some plywood over the one torn screen, but that left another forty feet of patio screen for Colt to slip through. And he’d already proved that the door lock was no contest. From Colt’s experience over the last few days, he must have thought things shut down early on the dock, leaving him plenty of dark hours to come back and raid Coakley’s and maybe take another shot at a taxi boat if he hadn’t found one elsewhere.

Tonight would be different, though, because of all the parties happening and people moving back and forth among islands. I wondered if Colt knew that.

I finished my beer and looked at the rum display. This would be a fine place to wait for Colt. I’ve spent many amiable afternoons that stretched into pleasantly lost evenings inside Bahamian rum shops. You order a bottle for your table and the bartender keeps you supplied with Cokes or fruit juice mixers. It’s one of the best ways to meet people because, like pubs in Ireland, Caribbean rum shops serve as the social centers of every small village.

Petagay broke my reverie, saying she was starving. I bought her a Honey Bun.

“No thanks,” she said. Cell service had popped up momentarily and her phone buzzed in a couple of messages. Two stories were floating around the island. “Some people are saying a boat was stolen today down in Governor’s Harbour. Others say a boat is missing from Harbour Island.” Denaldo added that he, too, had heard about a boat theft in Governor’s.

It was close to 10 p.m. Governor’s Harbour was a forty-mile drive south. Harbour Island was a ferry ride across the bay. Both rumors, though, said only that boats were missing. That could mean Colt had found his long-range craft and was already on his way farther down the chain to Cat Island or the Exumas. Both were a day’s travel by scheduled flights even though they were only twenty and thirty miles, respectively, from the southern tip of Eleuthera. And there was no way for me to even start a trip tonight. These were also just island rumors. I suddenly felt the sleeplessness of the last few days catching up with me. Even more, I realized I was hungry, too, and yeah, you’d have to be desperate to be in the Bahamas on Independence Day and settle for Honey Buns and Snickers bars. I turned to Petagay. “Let’s go to the Bluff.”

As I paid our tab, Denaldo remembered one more detail about the burglary.

“Oh yeah… he also took the emergency light.” He pointed to a spot on the wall where the battery still hung, part of a system designed to pop on whenever the power went out, which was frequently. The lights had been unplugged and taken. The grid had intermittingly blinked off Wednesday night, so Colt could have just been ensuring he wasn’t suddenly lit up inside Coakley’s. But why take the lights?

Another explanation for Colt’s machinations aboard the taxi boats suddenly made sense. By MacGyvering together Ricky Ricardo’s boat battery and Coakley’s fixture, Colt could create a powerful spotlight to illuminate a campsite or cave, or even to use on the front of a boat to help him navigate unfamiliar waters. His portable GPS worked well for charting general courses, but depending on the exact model—as well as meteorological conditions—it might be accurate only to within ten or fifteen yards. Like many, many boaters before him, Colt had already learned a tough lesson on the Devil’s Backbone: if you couldn’t see the myriad rocks, reefs, and sandbars in the Bahamas’ shallows with your own eyes, being off course by just a few feet could mean the difference between smooth sailing and coming to grief hard aground. If he was going to be boating after dark, a light would help him read the water in those shallow areas where just a couple hours of tidal rise separated a safe passage from bellying up to a sandbar.

THE TAXI DRIVERS HAD been right: the Bluff was definitely the place to be that night. We heard the music and smelled the barbecues a block away. People swarmed the waterfront, piling in front of the food and drink stands that lined the settlement’s large concrete dock. High-energy calypso pumped from the walls of speakers you find at even the smallest Bahamian public parties. At the booze booth I ordered a rum and Coke in an attempt to maintain the island vibe and stay awake at the same time. Petagay and I then sat on the seawall digging into huge plates of grilled lobster and cracked conch with mounds of peas ’n’ rice on the side.

Читать дальше