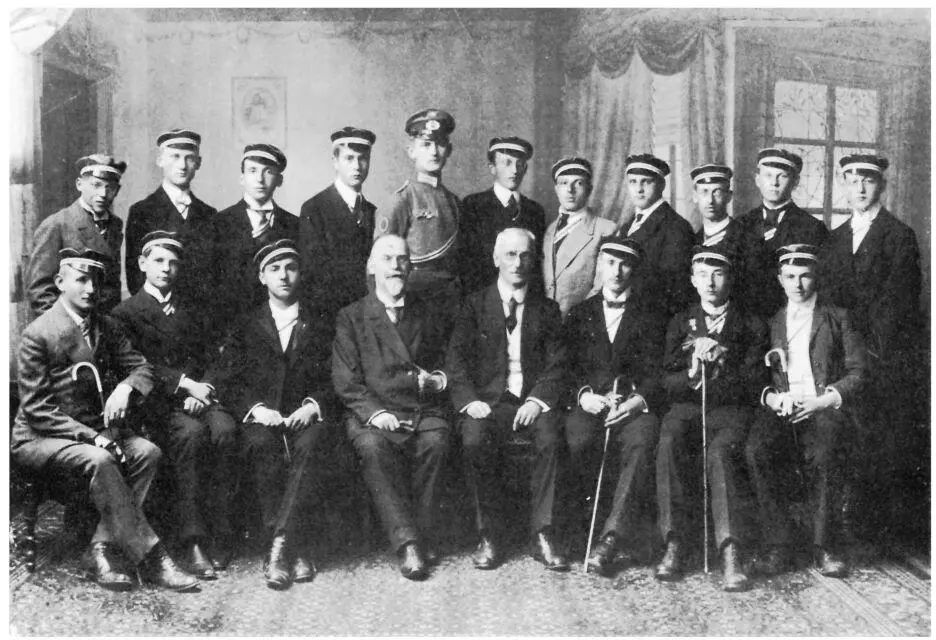

Himmler as a senior schoolboy at Landshut (front row, second from the right)

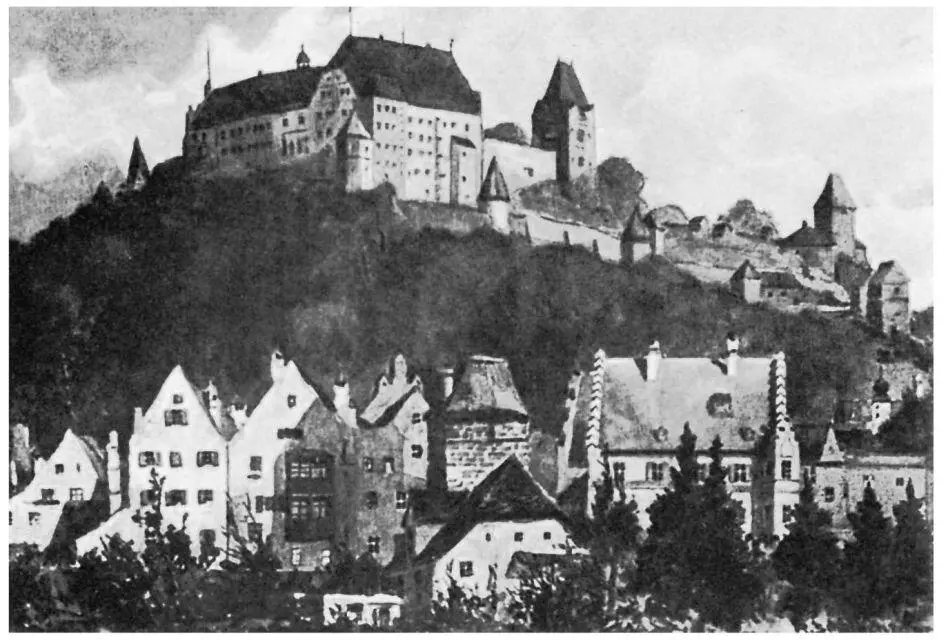

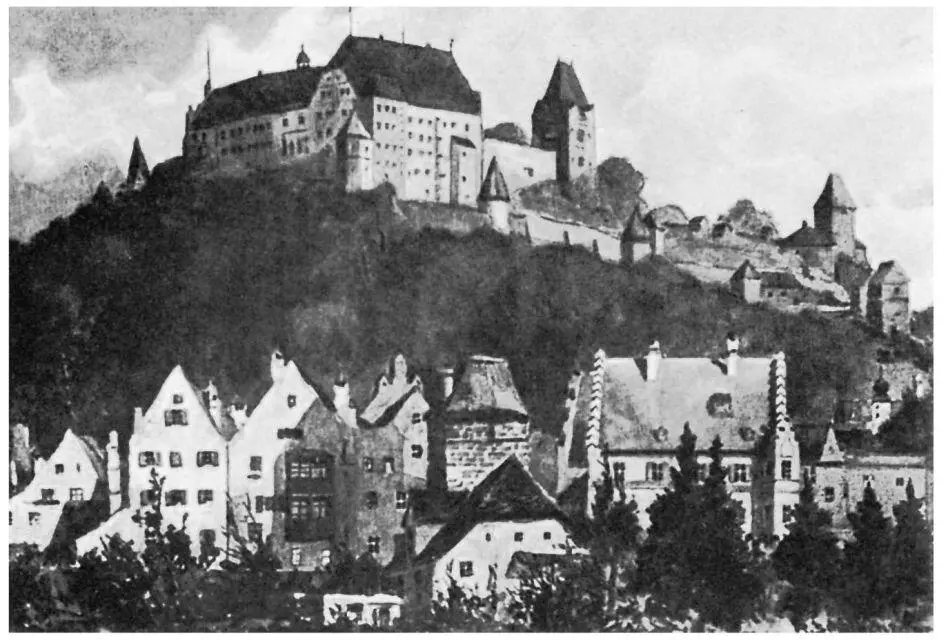

Landshut: the town where Himmler spent much of his youth. Himmler’s house is shown prominently at centre right

The apartment in Amalienstrasse where Himmler lived from 1904 to 1913

Now that the S.S. was an entirely independent force, responsible through Himmler only to Hitler himself, Himmler became absorbed in consolidating its membership and carrying still further his growing obsession with their racial purity and their loyalty to his idea of establishing them as a special Order in the Party and the State. His concern was more for the quality of the S.S. than for their numbers. As we have seen, he had already begun, before 30 June, to remove those men who had been too hurriedly recruited after the seizure of power and who failed to pass his stringent tests. According to Eberstein at Nuremberg, during the period 1934-5 some 60,000 men were released from the S.S. Nevertheless, the S.S. was kept at a strength in the region of 200,000 men and represented a formidable force which made the Army, already divided in its attitude to Hitler, increasingly anxious. But Himmler’s natural caution always made him wary of stirring up trouble. He preferred to work in secret, though he was always prepared to make public statements about the high standards he exacted from the S.S. and its undying dedication to Hitler.

From 1934 the S.S. was forbidden to take part in any troop manoeuvres with the Army, although some of its members were Army reservists, nor did its members openly receive a specifically military training. Nevertheless they were armed with small-calibre rifles and were trained to shoot. They were now vigorously selected for their Nordic excellence. As Himmler put it, the S.S. was to be ‘a National Socialist Soldier Order of Nordic Men’.

As Gisevius said when giving evidence at Nuremberg, 7‘The members had to be so-called Nordic types… if I am not mistaken, the distinguishing characteristics of men and women went as far as underarm perspiration.’ The moral deception involved in recruitment was, Gisevius claimed, often irreparable; men joined frequently out of an honest desire to assist a force dedicated, as it seemed, to order and decency in contrast to the degenerate hooliganism of the S.A., only to find themselves later involved in the criminal practices imposed on them by Heydrich and Himmler. Large numbers of the S.S. were part-time men who pursued their normal activities, except for special occasions and national emergencies, giving only spare time to their S.S. duties. The oath taken by every man on entering the S.S. was: ‘I swear to you, Adolf Hitler, as Führer and Reich Chancellor, loyalty and bravery. I vow to you, and to those you have named to command me, obedience unto death, so help me God.’ 8

Heydrich had in 1932 founded a leadership school at Bad-Toelz in Bavaria, a centre for training which was to be maintained, with considerable variation in its curriculum, until well into the years of the war. Heydrich was as much concerned with the intelligence as he was with the physique of the S.S. leader. Sport, gymnastics and other activities that imposed the meaning of discipline on the students were the basis of their education, together with the Nazi version of history, geography, militarism and racial consciousness.

Himmler was determined to establish a centre for the S.S. leadership which would be worthy of the racial purification they represented. Though Himmler’s mind had moved far from the Catholicism in which he had been brought up, the self-dedication of the Catholic monastic orders influenced him in devising his plans for this centre. Even Hitler compared him with Ignatius Loyola. Walter Schellenberg, who had studied both medicine and law at the University of Bonn and was one of the bright young intellectuals who joined Heydrich’s S.D., was later to become one of the inner circle of men who made a study of Himmler and learned how to control him. In his Memoirs he writes: ‘The S.S. organization had been built up by Himmler on the principles of the Order of the Jesuits. The service statutes and spiritual exercises presented by Ignatius Loyola formed a pattern which Himmler assiduously tried to copy.’ 9The Jesuitical ideal in Himmler’s mind merged with his medieval vision of the Teutonic knights, whose combination of religious observance and brutalized chivalry inspired him to found a similar S.S. Order of Knights in a Germanic castle of their own.

The Order of Teutonic Knights founded at the close of the twelfth century with the combined aim of conquest and conversion, had its centre in the castle of Marienburg, which became the residence of the Grand Master of the Order. The Teutonic Knights boasted alike of their valour and their statesmanship, their self-denial and their skill as administrators, and at the height of their power in the fourteenth century they stretched their conquests through Poland as far as the Baltic States. The image of the Grand Master became a part of Himmler’s obsession, but his mind, incapable of largeness of thought or inspiration, could only absorb simplified concepts from past history out of which he attempted to create dogmas for the present. He began to see himself as Grand Master of a modern Teutonic order designed to rid Nordic German society of degenerate infiltration by Jewish blood. Like the medieval Teutonic Knights, he also looked east towards that other great threat to German purity, the inferior Slav races with their evil communist doctrines. As he put it himself in 1936: ‘We shall take care that never again in Germany, the heart of Europe, will the Jewish-Bolshevistic revolution of sub-humans be kindled either from within or through emissaries from without.’ 10

For inspiration he founded the new Teutonic castle of Wewelsburg in the forests near Paderborn, an ancient town in Westphalia with historic associations that went back to Charlemagne. Wewelsburg was built on the foundations of a medieval burgh; it was designed for him by an architect called Bartels and took a year to construct, at a cost of some 11 million marks.

According to Schellenberg, the castle was run like a monastery and a hierarchic order of leadership after the pattern of the Catholic Church was imposed on those members of the S.S. privileged to visit Wewelsburg for the regular retreats organized by Himmler, who was, in Jesuitical terms, General of the Order. Each member of the secret Chapter had his own chair with a silver name-plate, and ‘each had to devote himself to a ritual of spiritual exercises aimed mainly at concentration’, the equivalent of prayer, before discussing the higher policy of the S.S. 11

Wewelsburg was Himmler’s only indulgence in the kind of luxury with which most of the Nazi leaders were surrounded. The castle was as magnificently appointed in the medieval manner as Carinhall, Göring’s vast residence north of Berlin which he was extending and reconstructing at the same time as Himmler was building Wewelsburg. The design and association of the rooms were supposed to conjure the spirit of Germany’s greatness; each was named after an historic figure such as Frederick the Great, and a collection of relics of the past was assembled in the castle’s museum. Himmler’s own room was named after Heinrich I, Henry the Fowler, the king who a thousand years before had been the founder of the German Reich.

Читать дальше