Both men were quite intent on catching me. I continued to run, however, at top speed. Falling farther and farther behind, they cursed me and swore my death upon capture. I struggled on. Luckily, I had taken the vehicle not far from my home (I lived on Sixty-ninth Street and I had taken the car on Sixty-sixth). Therefore, my run was not that far.

Rounding the corner onto my block I was elated to see that my pursuers were at least four houses behind me. I darted down the drive of our next-door neighbor and hopped the fence into our backyard. I then staggered heavily into the house and literally collapsed on my mother’s bed. Pulling myself up, I began to discard my clothing, putting on fresh pants, socks, and sneakers. I deliberately omitted a shirt, so as to look as at-home as possible, just in case.

Not ten minutes later, I heard the police helicopter hovering over my house. I felt good at least to know that my mother was, as usual, at work. Five minutes after I heard the first hum of the helicopter, I heard voices coming from the front room. I quickly hid myself in my mother’s closet, to no avail. I was violently pulled from the closet and promptly arrested. I later found out that it was a mentally ill cat name Theapolis who had snitched me off to my pursuers, who in turn summoned the police.

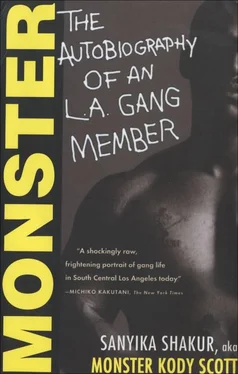

During the trial on assault and grand theft auto charges, my sister, Kendis, perjured herself to save me from a jail term, but was not convincing enough against thirteen witnesses who had originally given chase. I was subsequently convicted and sentenced to nine months in camp. (Camp is the third testing ground in a series of “tests” to register one’s ability to “stand firm,” the streets, of course, being the first and juvenile hall the second. With each successive level—the Hall, camp, Youth Authority, prison—comes longer, harder time. This, coupled with a greater danger of becoming a victim, pits one hard against the total warrior mentality of “Do or Die.” Here, the slogan ends and reality sets in.)

Nine months later I was released from Camp Munz and dropped off in the initial stages of a war that would forever change the politics of Gripping and the internal gang relations in South Central. Although my camp term lent prestige to my name, it did little to help me break through to the desperately sought-after second level of recognition. Crazy De, I learned, was due out in December, so I just did “odd jobs”—wrote on walls, i.e., advertised; collected guns; and maintained visibility.

It was during my stay in camp that my younger brother chose to follow me into banging and ally himself with the Eight Trays. Seventy-nine was the year of the Li’l’s, that is, the year of the third generation of Eight Tray gangsters. All those who were of the second resurrection—beginning in 1975 and ending in 1977—acquired little homies bearing their names. For example, there was Li’l Monster, Li’l Crazy De, Li’l Spike, etc. In a nine-month period, the set doubled.

Meanwhile, the war between us and the Rollin’ Sixties was beginning to heat up. The first casualty was on their side. Tyrone, the brother of an O.G. Sixty, was gunned down during a routine fistfight by a new recruit calling himself Dog. The O.G. whose brother had been killed wanted us to produce the shooter before a full-scale war broke out. The shooter, who few of us knew, as he was new, immediately went into hiding. We thus could not produce him and our relationship with the Sixties soured dramatically.

Up until that point only one of our homies had been killed, and his death was attributed to the Inglewood Families. Threats of revenge grew loud, as did rumors of an imminent war. In the midst of these warnings, our homeboy Lucky was ambushed on his porch and shot six times in the face. Witnesses reported seeing “a man in a brown jogging suit flee the area immediately after shots rang out.” The night Lucky was murdered, Mumpy, a member of the Sixties, was seen at Rosecrans Skating Rink in a brown jogging suit. It had been further noted that Mumpy had been heard telling Lucky that “since one of my homeboys died, one of yours gotta die.” A fight had ensued and had subsequently been broken up by members of both sides.

After Lucky’s death tension ran high in our ’hood. We wanted the shooters to fall under the weight of our wrath. A meeting of both sets was called by the O.G.s, in an all-out last effort to curtail a war, which would no doubt have grave consequences. The most damaging thing that we all held in mind was that we all knew where one another stayed—not more than six months before we had been the best of friends. The meeting was a dismal failure. It erupted into an all-out gang fight reminiscent of the old gang “rumbles.” Diplomatic ties were thus broken, and war was ceremoniously declared. Another casualty quickly accrued to their side, as their homeboy Pimp was ambushed and killed. Several others were wounded.

At about that time, De was released. I relayed to him the drastic chain of events of recent times, and we both chose to give one hundred percent to the war effort. And perhaps, we concurred, this was the issue to carry us both over into the second realm of recognition on our climb to O.G. status.

In retaliation for Pimp’s death—which the Sixties without a doubt attributed to us—our homie Tit Tit was shot, and while he lay in the street, mortally wounded, the gunmen came back around the corner in a white van. Before we could retrieve Tit Tit, they ran his head over and continued on. The occupants in the van had also shot two other people before shooting and killing Tit Tit, though both were civilians. This was the second homie to die in a matter of months. Shit was getting major.

Although we had been engaged in a war with the Families, it had always, somehow, been contained to fistfights and flesh wounds, with the exception of Shannon—who, we contend to this day, died at the hands of the Families. This escalation was new and actually quite alarming, for Crips tend to display a vicious knack for violence against other Crips—as will be duly noted in following chapters. Seemingly every Crip set erupted in savage wars, one against the other, culminating into the Beiruttype atmosphere in South Central today.

The news-catching items of violence to date are a result of clashes between Crips and Crips and not, as the media suggests, “Red and Blue,” “Crip and Blood.” Once bodies began to drop, people who were less than serious about banging began to fall by the wayside. Excuses of having to “be home by dark” and to “go out of town” abounded. The set thus dwindled to, I would learn, fighting shape.

De and I held fast and “seized the time.” China, a very pretty but slightly plump homegirl, became my steady girl. She and I would often dress alike to further prompt our union.

China lent me her eight-track tape player. One afternoon, as De and I were walking with China’s radio, we drew fire from a passing car—no doubt Sixties. Unscathed but very angry, De and I climbed from the bushes.

“Check this out.” De spoke with barely controlled anger. “Kody, we gotta put a stop to these muthafuckas shootin’ at us and shit.”

Looking at me hard in search of some signs of overstanding and compliance, I said, “You right, homie, I’m wit’ it.”

“You serious?” De gave me a sinister smile. “All right then,” he continued, “let’s make a pact right now to never stop until we have killed all of our enemies. This means wherever we catch ’em, it’s on!”

“All right, I’m serious, De,” I said as I pledged my life to the Sixties’ total destruction, or mine—whichever came first.

With that, I spun and threw China’s radio high into the air as an all-out gesture of total abandonment. The radio seemed to tumble in slow motion, twisting and twirling as my gang life up until that time flashed in vivid episodes across my mental screen. From graduation to this—blam! The radio hit the ground, shattered into a hundred pieces, and the screen in my mind went blank.

Читать дальше