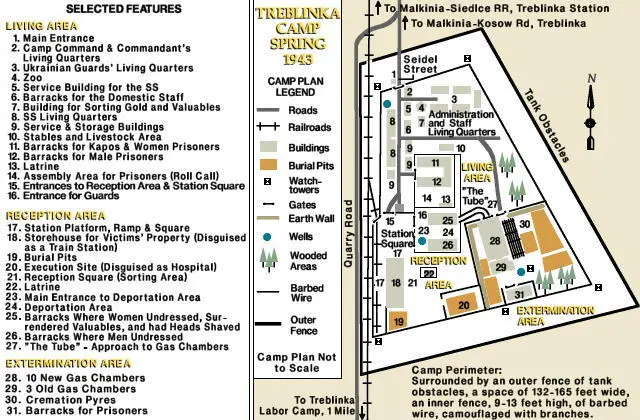

— We arrived in Treblinka in early September 1944, thirteen months after the day of the uprising. For thirteen months from July 1942 the executioner’s block had been at work — and for thirteen months from August 1943, the Germans had been trying to obliterate every trace of this work.

It is quiet. The tops of the pine trees on either side of the railway line are barely stirring. It is these pines, this sand, this old tree stump that millions of human eyes saw as their freight wagons came slowly up to the platform. With true German neatness, whitewashed stones have been laid along the borders of the black road. The ashes and crushed cinders swish softly. We enter the camp. We tread the earth of Treblinka. The lupin pods split open at the least touch; they split with a faint ping and millions of tiny peas scatter over the earth. The sounds of the falling peas and the bursting pods come together to form a single soft, sad melody. It is as if a funeral knell — a barely audible, sad, broad, peaceful tolling — is being carried to us from the very depths of the earth. And, rich and swollen as if saturated with flax oil, the earth sways beneath our feet — earth of Treblinka, bottomless earth, earth as unsteady as the sea. This wilderness behind a barbed-wire fence has swallowed more human lives than all the earth’s oceans and seas have swallowed since the birth of mankind.

The earth is casting up fragments of bone, teeth, sheets of paper, clothes, things of all kinds. The earth does not want to keep secrets.

And from the earth’s unhealing wounds, from this earth that is splitting apart, things are escaping of their own accord. Here they are: the half-rotted shirts of those who were murdered, their trousers and shoes, their cigarette cases that have turned green, along with little cog-wheels from watches, pen-knives, shaving brushes, candlesticks, a child’s shoes with red pompoms, embroidered towels from the Ukraine, lace underwear, scissors, thimbles, corsets and bandages. Out of another fissure in the earth have escaped heaps of utensils: frying pans, aluminium mugs, cups, pots and pans of all sizes, jars, little dishes, children’s plastic mugs. In yet another place — as if all that the Germans had buried was being pushed up out of the swollen, bottomless earth, as if someone’s hand were pushing it all out into the light of day: half-rotted Soviet passports, notebooks with Bulgarian writing, photographs of children from Warsaw and Vienna, letters pencilled in a childish scrawl, a small volume of poetry, a yellowed sheet of paper on which someone had copied a prayer, ration cards from Germany… And everywhere there are hundreds of perfume bottles of all shapes and sizes — green, pink, blue… And over all this reigns a terrible smell of decay, a smell that neither fire, nor sun, nor rain, nor snow, nor wind have been able to overcome. And thousands of little forest flies are crawling about over all these half-rotted bits and pieces, over all these papers and photographs.

We walk on over the swaying, bottomless earth of Treblinka and suddenly come to a stop. Thick wavy hair, gleaming like burnished copper, the delicate lovely hair of a young woman, trampled into the ground; and beside it, some equally fine blonde hair; and then some heavy black plaits on the bright sand; and then, more and more… Evidently these are the contents of a sack, just a single sack that somehow got left behind. Yes, it is all true. The last hope, the last wild hope that it was all just a terrible dream, has gone. And the lupin pods keep popping open, and the tiny peas keep pattering down — and this really does all sound like a funeral knell rung by countless little bells from under the earth. And it feels as if your heart must come to a stop now, gripped by more sorrow, more grief, more anguish than any human being can endure…

Scholars, sociologists, criminologists, psychiatrists and philosophers — everyone is asking how all this can have happened.

How indeed? Was it something organic? Was it a matter of heredity, upbringing, environment or external conditions? Was it a matter of historical fate, or the criminality of the German leaders?

Somehow the embryonic traits of a racial theory that sounded simply comic when expounded by the second-rate charlatan professors or pathetic provincial theoreticians of nineteenth-century Germany — the contempt in which the German philistine held “Russian pigs”, “Polish cattle”, “Jews reeking of garlic”, “debauched Frenchmen”, “English shopkeepers”, “hypocritical Greeks” and “Czech blockheads”; all the nonsense about the superiority of the Germans to every other race on earth, all the cheap nonsense that seemed so comical, such an easy target for journalists and humorists — all this, in the course of only a few years, ceased to seem merely infantile and was transformed into a threat to mankind. It became a deadly threat to human life and freedom and a source of unparalleled crime, bloodshed and suffering. There is much now to think about, much that we must try to understand.

Wars like the present war are terrible indeed. A vast amount of innocent blood has been spilt by the Germans. But it is not enough now to speak about Germany’s responsibility for what has happened. Today we need to speak about the responsibility of every nation in the world; we need to speak about the responsibility of every nation and every citizen for the future.

Every man and woman today is duty-bound to his or her conscience, to his or her son and to his or her mother, to their motherland and to humanity as a whole to devote all the powers of their heart and mind to answering these questions: what is it that has given birth to racism? What can be done to prevent Nazism from ever rising again, either on this side or on the far side of the ocean? What can be done to make sure that Hitlerism is never, never in all eternity, resurrected?

What led Hitler and his followers to construct Majdanek, Sobibór, Bełżec, Auschwitz and Treblinka is the imperialist idea of exceptionalism — of racial, national and every other kind of exceptionalism.

We must remember that Fascism and racism will emerge from this war not only with the bitterness of defeat but also with sweet memories of the ease with which it is possible to commit mass murder. It has turned out that it is really not so very difficult to kill entire nations. Ten small chambers — hardly enough space, if properly furnished, to stable a hundred horses — ten such chambers turned out to be enough to kill three million people.

Killing turned out to be supremely easy — it does not entail any uncommon expenditure.

It is possible to build five hundred such chambers in only a few days. This is no more difficult than constructing a five-storey building.

It is possible to demonstrate with nothing more than a pencil that any large construction company with experience in the use of reinforced concrete can, in the course of six months and with a properly organized labour force, construct more than enough chambers to gas the entire population of the earth.

This must be unflinchingly borne in mind by everyone who truly values honour, freedom and the life of all nations, the life of humanity.

Translated from the Russian by Robert Chandler

Treblinka: testimony and reportage Richard Glazar, Trap with a Green Fence: Survival in Treblinka , trans.

Roslyn Theobald (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1995)

Vasily Grossman, The Road: Short Fiction and Essays, trans. Robert and Elizabeth Chandler with Olga Mukovnikova (London: MacLehose Press, 2010)

Читать дальше

![Нед Виззини - Be More Chill [Расслабься] [litres]](/books/396819/ned-vizzini-be-more-chill-rasslabsya-litres-thumb.webp)