At the far end was an enormous framed picture of Hitler, his eyes staring straight at me. Behind me was Göring. I could just see his face over my shoulder if I turned my head slightly and that made me feel even more nervous. Who was going to come out of the door the other side and along that corridor? I would be going through there any minute. Somebody was going to come out and call my name. Me, all on my own in this place. I could have done with a friend right then. I was wondering if I would see Laurie and Jimmy or Sid and Heb again. Had they finished work and were having lunch? Soup again, no doubt. Maybe they were having a crafty smoke behind the stables.

It felt a long time standing to attention but it was probably about five minutes when Jan decided he had had enough. He was standing to the side of me, his rifle propped up against the wall. Now I had the feeling all along that Jan was a bit of an idiot. Fancy leaving your rifle propped up when guarding a prisoner for a start – and in a place like this. He walked round the front of me and said, ‘ Bleiben hier. Ja. ’ – stay here, yes. I understood and replied ‘ Ja ’. He walked off and away down the steps and disappeared. I could hear voices and he was asking somebody about a drink – ‘ Zu trinken ,’ and if there was a canteen – ‘ Wo ist die Kantine ? He didn’t come back so I just remained standing there on my own waiting for something to happen.

Suddenly two German officers appeared from the other end and they walked towards the opening where their offices were, I imagined. Those boots again, with those steel tips and heels, which went clack, clack, clacking across the polished wooden floor. To give them due, they were the smartest looking officers, and their uniforms were way above anything I had ever seen. Immaculate, everything beautifully polished and starched. They really were just the ticket. One was wearing the Iron Cross on a ribbon round his neck, and there wasn’t a crease in his uniform. They disappeared for a little while and then I heard the boots again. They came back and one said something to the other one.

Oh, God, what was that? Iron Cross came over to speak to me and I was taken aback. He said in absolutely perfect English. ‘Who are you and what are you doing here?’ and I thought, Thank God, an English man! You could always tell a German trying to speak English by their pronunciation of zee instead of th as in the; but there was no trace of that. It was laughable. I was so relieved and then immediately felt frightened again. If he was English and turned German I was in serious trouble. He could be really hostile to any fellow Englishman if he had turned against his own country. If they were going to try me then things could get much worse for me.

‘Where is the guard?’

‘I don’t know, sir.’

‘Has he gone to the office?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Has he gone out?’

So I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ I told him the truth. ‘He went out.’

So Iron Cross went to the far end, opened the door and called out, ‘ Gehen und ihn! ’ – go and get him.

I was watching all this going on when I saw Jan come back in. The silly idiot came up the steps, pushed the door open, entered and stood beside me. He didn’t look over the other side where the two officers were standing right under Hitler. When he finally looked up and across, he saw them, grabbed his rifle and stood to attention. What else could he do? The officers crossed the floor again towards him. Jan stood to attention and they all exchanged ‘ Heil Hitler’ . Iron Cross gave him a terrible dressing down. You didn’t need to speak German to understand what he said. And then they went off back inside and we were left standing there again.

I thought that had helped me a bit; he was in trouble and that might make it easier for me when they came to deal with me. But then I found out that they were nothing to do with me, too high-ranking to be hearing a case like mine.

Clack, clack, more heels, but female ones this time, and a woman in civilian clothes appeared and said something to the guard in German. Jan grabbed hold of my epaulette and started pulling me along as he followed the woman down the corridor. She entered the room first and my guard pushed me inside and disappeared.

There were two officers sitting behind a large desk. One looked like a 2nd Lieutenant and the other a Sergeant Major, Hauptfeldwebel. At the far end of the room at another table sat a uniformed woman tapping away on one of those large sit-up-and-beg manual typewriters. One asked me my name again ‘ Name und Nummer ’ and I said it again. The civilian woman looked on silently. I thought she was probably from the Red Cross and if this was my trial then she was here as a neutral observer to see that things were done correctly. I wished she would say something to me; a word of comfort wouldn’t have gone amiss. The other officer asked me my name and number again and pushed a foolscap sheet of paper across the table to me along with a pen. I was trembling and my palms were sweating. What was this? Didn’t I get the chance to speak? I bent down to pick the pen up and I looked at the paper. Of course it was all in German. No idea what it said. So I put the pen down and pushed the piece of paper back to him.

‘ Ich verstehe nicht. ’ – I don’t understand, I said.

‘Egal, ‘ – doesn’t matter, was the reply and he pushed the paper back to me.

I pushed it away again. ‘ Ich verstehe nicht. ’ As scared as I was, I was not going to sign that piece of paper. I could have been signing my death warrant for all I knew. So I didn’t sign and left it on the table and stood to attention.

The officers looked at each other and started talking; they consulted Red Cross Lady who nodded and left the room. A moment later, she returned with a middle-aged chap in uniform who told me, in broken English, that he had been a prisoner of war in England at the end of the last war. So with his bit of English and my bit of German I learned that the charge of ‘Incitement to Mutiny’ had been dropped and changed to a lesser one of ‘Sabotage, wasting food and damaging army property’. I was so relieved that I nearly cried with relief. Although I was still frightened about what would happen next.

My guard was called back in and off we went again. Jan was still pulling me by my epaulette, taking the same way back. Across the squares, through the gates, on to the road to the station, on to a train, and so on, back to camp. It was dark when I got in and my pals were there, pleased to see me.

Jimmy patted me on the back and said something like, ‘A wee break like that does you the world o’ good.’ Sid gave me bit of bread and butter that he had kept back from supper. Laurie lit me up a cigarette and Heb said, ‘Good to see you in one piece.’

And that was it. I didn’t hear any more about it. It sort of fizzled out. I got away with it, or so I thought.

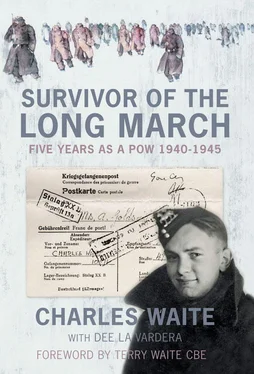

A week passed before I heard anything more; I really thought they had forgotten about it. Jan was still around on duty but he never came out on any job I was on. It was Friday after work and the guards had got us lined up outside. The Unteroffizier arrived and called out my name again. I stepped forward. He held two cards and handed me one typed in English and read out the other in German. I was to be taken to Stalag 20B to do ten days’ solitary confinement. And I was scared all over again.

I went to collect my things, my greatcoat and bundle. My pals rallied round. ‘Don’t worry, could have been worse,’ and collected what biscuits they had saved from their last Red Cross parcels. ‘You’ll be all right.’ I had three or four biscuits of my own and they added some more until I had about a dozen in the end, wrapped in a scrap of paper. A real feast. ‘Got to save ’em. Don’t know when you’ll eat again,’ they said to me.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)