Charles Oman

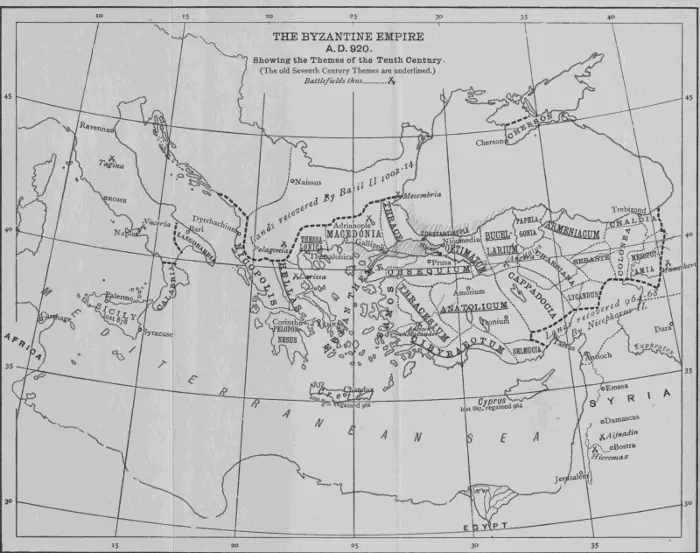

History of the Byzantine Empire: From the Foundation until the Fall of Constantinople (328-1453)

The Rise and Decline of the Eastern Roman Empire

Published by

Books

Books

Advanced Digital Solutions & High-Quality eBook Formatting

musaicumbooks@okpublishing.info2018 OK Publishing ISBN 978-80-272-4108-8

Preface. Preface. Table of Contents Fifty years ago the word “Byzantine” was used as a synonym for all that was corrupt and decadent, and the tale of the East-Roman Empire was dismissed by modern historians as depressing and monotonous. The great Gibbon had branded the successors of Justinian and Heraclius as a series of vicious weaklings, and for several generations no one dared to contradict him. Two books have served to undeceive the English reader, the monumental work of Finlay, published in 1856, and the more modern volumes of Mr. Bury, which appeared in 1889. Since they have written, the Byzantines no longer need an apologist, and the great work of the East-Roman Empire in holding back the Saracen, and in keeping alive throughout the Dark Ages the lamp of learning, is beginning to be realized. The writer of this book has endeavoured to tell the story of Byzantium in the spirit of Finlay and Bury, not in that of Gibbon. He wishes to acknowledge his debts both to the veteran of the war of Greek Independence, and to the young Dublin professor. Without their aid his task would have been very heavy—with it the difficulty was removed. The author does not claim to have grappled with all the chroniclers of the Eastern realm, but thinks that some acquaintance with Ammianus, Procopius, Maurice's “Strategikon,” Leo the Deacon, Leo the Wise, Constantine Porphyrogenitus, Anna Comnena and Nicetas, may justify his having undertaken the task he has essayed. Oxford, February, 1892.

I. Byzantium.

II. The Foundation Of Constantinople. (A.D. 328-330.)

III. The Fight With The Goths.

IV. The Departure Of The Germans.

V. The Reorganization Of The Eastern Empire. (A.D. 408-518.)

VI. Justinian.

VII. Justinian's Foreign Conquests.

VIII. The End Of Justinian's Reign.

IX. The Coming Of The Slavs.

X. The Darkest Hour.

XI. Social And Religious Life. (A.D. 320-620.)

XII. The Coming Of The Saracens.

XIII. The First Anarchy.

XIV. The Saracens Turned Back.

XV. The Iconoclasts. (A.D. 720-802.)

XVI. The End Of The Iconoclasts. (A.D. 802-886.)

XVII. The Literary Emperors And Their Time. (A.D. 886-963.)

XVIII. Military Glory.

XIX. The End Of The Macedonian Dynasty.

XX. Manzikert. (1057-1081.)

XXI. The Comneni And The Crusades.

XXII. The Latin Conquest Of Constantinople.

XXIII. The Latin Empire And The Empire Of Nicaea. (1204-1261.)

XXIV. Decline And Decay. (1261-1328.)

XXV. The Turks In Europe.

XXVI. The End Of A Long Tale. (1370-1453.)

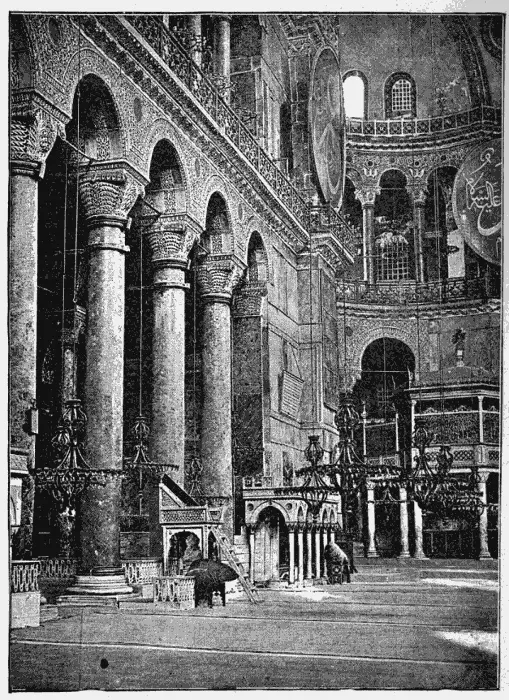

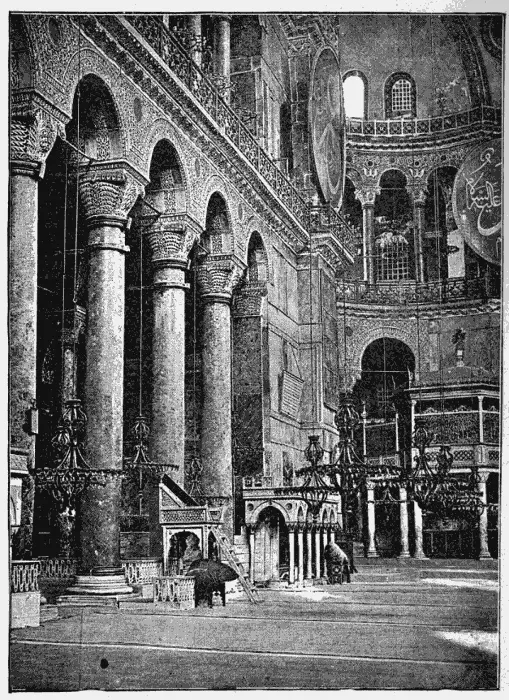

Interior of St. Sophia

Interior of St. Sophia

Table of Contents

Fifty years ago the word “Byzantine” was used as a synonym for all that was corrupt and decadent, and the tale of the East-Roman Empire was dismissed by modern historians as depressing and monotonous. The great Gibbon had branded the successors of Justinian and Heraclius as a series of vicious weaklings, and for several generations no one dared to contradict him.

Two books have served to undeceive the English reader, the monumental work of Finlay, published in 1856, and the more modern volumes of Mr. Bury, which appeared in 1889. Since they have written, the Byzantines no longer need an apologist, and the great work of the East-Roman Empire in holding back the Saracen, and in keeping alive throughout the Dark Ages the lamp of learning, is beginning to be realized.

The writer of this book has endeavoured to tell the story of Byzantium in the spirit of Finlay and Bury, not in that of Gibbon. He wishes to acknowledge his debts both to the veteran of the war of Greek Independence, and to the young Dublin professor. Without their aid his task would have been very heavy—with it the difficulty was removed.

The author does not claim to have grappled with all the chroniclers of the Eastern realm, but thinks that some acquaintance with Ammianus, Procopius, Maurice's “Strategikon,” Leo the Deacon, Leo the Wise, Constantine Porphyrogenitus, Anna Comnena and Nicetas, may justify his having undertaken the task he has essayed.

Oxford,

February, 1892.

Table of Contents

Two thousand five hundred and fifty-eight years ago a little fleet of galleys toiled painfully against the current up the long strait of the Hellespont, rowed across the broad Propontis, and came to anchor in the smooth waters of the first inlet which cuts into the European shore of the Bosphorus. There a long crescent-shaped creek, which after-ages were to know as the Golden Horn, strikes inland for seven miles, forming a quiet backwater from the rapid stream which runs outside. On the headland, enclosed between this inlet and the open sea, a few hundred colonists disembarked, and hastily secured themselves from the wild tribes of the inland, by running some rough sort of a stockade across the ground from beach to beach. Thus was founded the city of Byzantium.

The settlers were Greeks of the Dorian race, natives of the thriving seaport-state of Megara, one of the most enterprising of all the cities of Hellas in the time of colonial and commercial expansion which was then at its height. Wherever a Greek prow had cut its way into unknown waters, there Megarian seamen were soon found following in its wake. One band of these venturesome traders pushed far to the West to plant colonies in Sicily, but the larger share of the attention of Megara was turned towards the sunrising, towards the mist-enshrouded entrance of the Black Sea and the fabulous lands that lay beyond. There, as legends told, was to be found the realm of the Golden Fleece, the Eldorado of the ancient world, where kings of untold wealth reigned over the tribes of Colchis: there dwelt, by the banks of the river Thermodon, the Amazons, the warlike women who had once vexed far-off Greece by their inroads: there, too, was to be found, if one could but struggle far enough up its northern shore, the land of the Hyperboreans, the blessed folk who dwell behind the North Wind and know nothing of storm and winter. To seek these fabled wonders the Greeks sailed ever North and East till they had come to the extreme limits of the sea. The riches of the Golden Fleece they did not find, nor the country of the Hyperboreans, nor the tribes of the Amazons; but they did discover many lands well worth the knowing, and grew rich on the profits which they drew from the metals of Colchis and the forests of Paphlagonia, from the rich corn lands by the banks of the Dnieper and Bug, and the fisheries of the Bosphorus and the Maeotic Lake. Presently the whole coastland of the sea, which the Greeks, on their first coming, called Axeinos—“the Inhospitable”—became fringed with trading settlements, and its name was changed to Euxeinos—“the Hospitable”—in recognition of its friendly ports. It was in a similar spirit that, two thousand years later, the seamen who led the next great impulse of exploration that rose in Europe, turned the name of the “Cape of Storms” into that of the “Cape of Good Hope.”

Читать дальше

Books

Books Interior of St. Sophia

Interior of St. Sophia