To fill the vast limits of his city, Constantine invited many senators of Old Rome and many rich provincial proprietors of Greece and Asia to take up their abode in it, granting them places in his new senate and sites for the dwellings they would require. The countless officers and functionaries of the imperial court, with their subordinates and slaves, must have composed a very considerable element in the new population. The artizans and handicraftsmen were enticed in thousands by the offer of special privileges. Merchants and seamen had always abounded at Byzantium, and now flocked in numbers which made the old commercial prosperity of the city seem insignificant. Most effective—though most demoralizing—of the gifts which Constantine bestowed on the new capital to attract immigrants was the old Roman privilege of free distribution of corn to the populace. The wheat-tribute of Egypt, which had previously formed part of the public provision of Rome, was transferred to the use of Constantinople, only the African corn from Carthage being for the future assigned for the subsistence of the older city.

On the completion of the dedication festival in 330 a.d. an imperial edict gave the city the title of New Rome, and the record was placed on a marble tablet near the equestrian statue of the emperor, opposite the Strategion. But “New Rome” was a phrase destined to subsist in poetry and rhetoric alone: the world from the first very rightly gave the city the founder's name only, and persisted in calling it Constantinople.

III. The Fight With The Goths.

Table of Contents

Constantine lived seven years after he had completed the dedication of his new city, and died in peace and prosperity on the 22nd of May, a.d. 337, received on his death-bed into that Christian Church on whose verge he had lingered during the last half of his life. By his will he left his realm to be divided among his sons and nephews; but a rapid succession of murders and civil wars thinned out the imperial house, and ended in the concentration of the whole empire from the Forth to the Tigris under the sceptre of Constantius II., the second son of the great emperor. The Roman world was not yet quite ripe for a permanent division; it was still possible to manage it from a single centre, for by some strange chance the barbarian invasions which had troubled the third century had ceased for a time, and the Romans were untroubled, save by some minor bickerings on the Rhine and the Euphrates. Constantius II., an administrator of some ability, but gloomy, suspicious, and unsympathetic, was able to devote his leisure to ecclesiastical controversies, and to dishonour himself by starting the first persecution of Christian by Christian that the world had seen. The crisis in the history of the empire was not destined to fall in his day, nor in the short reign of his cousin and successor, Julian, the amiable and cultured, but entirely wrongheaded, pagan zealot, who strove to put back the clock of time and restore the worship of the ancient gods of Greece. Both Constantius and Julian, if asked whence danger to the empire might be expected, would have pointed eastward, to the Mesopotamian frontier, where their great enemy, Sapor King of Persia, strove, with no very great success, to break through the line of Roman fortresses that protected Syria and Asia Minor.

But it was not in the east that the impending storm was really brewing. It was from the north that mischief was to come.

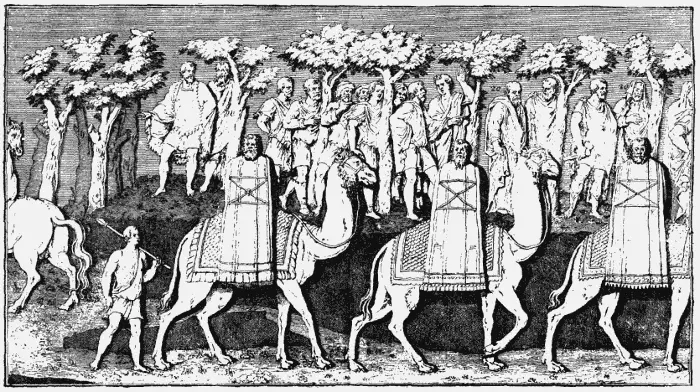

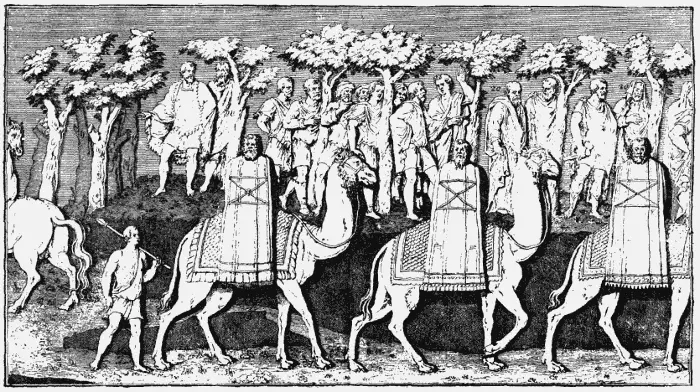

Gothic Idols. ( From the Column of Arcadius .)

Gothic Idols. ( From the Column of Arcadius .)

For a hundred and fifty years the Romans had been well acquainted with the tribes of the Goths, the most easterly of the Teutonic nations who lay along the imperial border. All through the third century they had been molesting the provinces of the Balkan Peninsula by their incessant raids, as we have already had occasion to relate. Only after a hard struggle had they been rolled back across the Danube, and compelled to limit their settlements to its northern bank, in what had once been the land of the Dacians. The last struggle with them had been in the time of Constantine, who, in a war that lasted from a.d. 328 to a.d. 332, had beaten them in the open field, compelled their king to give his sons as hostages, and dictated his own terms of peace. Since then the appetite of the Goths for war and adventure seemed permanently checked: for forty years they had kept comparatively quiet and seldom indulged in raids across the Danube. They were rapidly settling down into steady farmers in the fertile lands on the Theiss and the Pruth; they traded freely with the Roman towns of Moesia; many of their young warriors enlisted among the Roman auxiliary troops, and one considerable body of Gothic emigrants had been permitted to settle as subjects of the empire on the northern slope of the Balkans. By this time many of the Goths were becoming Christians: priests of their own blood already ministered to them, and the Bible, translated into their own language, was already in their hands. One of the earliest Gothic converts, the good Bishop Ulfilas—the first bishop of German blood that was ever consecrated—had rendered into their idiom the New Testament and most of the Old. A great portion of his work still survives, incomparably the most precious relic of the old Teutonic tongues that we now possess.

The Goths were rapidly losing their ancient ferocity. Compared to the barbarians who dwelt beyond them, they might almost be called a civilized race. The Romans were beginning to look upon them as a guard set on the frontier to ward off the wilder peoples that lay to their north and east. The nation was now divided into two tribes: the Visigoths, whose tribal name was the Thervings, lay more to the south, in what are now the countries of Moldavia, Wallachia, and Southern Hungary; the Ostrogoths, or tribe of the Gruthungs, lay more to the north and east, in Bessarabia, Transylvania, and the Dniester valley.

But a totally unexpected series of events were now to show how prescient Constantine had been, in rearing his great fortress-capital to serve as the central place of arms of the Balkan Peninsula.

About the year a.d. 372 the Huns, an enormous Tartar horde from beyond the Don and Volga, burst into the lands north of the Euxine, and began to work their way westward. The first tribe that lay in their way, the nomadic race of the Alans, they almost exterminated. Then they fell upon the Goths. The Ostrogoths made a desperate attempt to defend the line of the Dniester against the oncoming savages—“men with faces that can hardly be called faces—rather shapeless black collops of flesh with little points instead of eyes; little in stature, but lithe and active, skilful in riding, broad shouldered, good at the bow, stiff-necked and proud, hiding under a barely human form the ferocity of the wild beast.” But the enemy whom the Gothic historian describes in these uninviting terms was too strong for the Teutons of the East. The Ostrogoths were crushed and compelled to become vassals of the Huns, save a remnant who fought their way southward to the Wallachian shore, near the marshes of the Delta of the Danube. Then the Huns fell on the Visigoths. The wave of invasion pressed on; the Bug and the Pruth proved no barrier to the swarms of nomad bowmen, and the Visigoths, under their Duke Fritigern, fell back in dismay with their wives and children, their waggons and flocks and herds, till they found themselves with their backs to the Danube. Surrender to the enemy was more dreadful to the Visigoths than to their eastern brethren; they were more civilized, most of them were Christians, and the prospect of slavery to savages seems to have appeared intolerable to them.

Читать дальше

Gothic Idols. ( From the Column of Arcadius .)

Gothic Idols. ( From the Column of Arcadius .)